I first hear it the way many people still do: late at night, when the busy edges of the day quiet and old songs seem larger than their two and a half minutes. The radio fades in with a soft drum thump, voices paired so closely the vowels seem to touch. There’s that gentle lilt to the melody—equal parts homesick and hopeful—and a refrain that glows without grandstanding. Even before the chorus lands, “A World Without Love” feels like a hand on the shoulder.

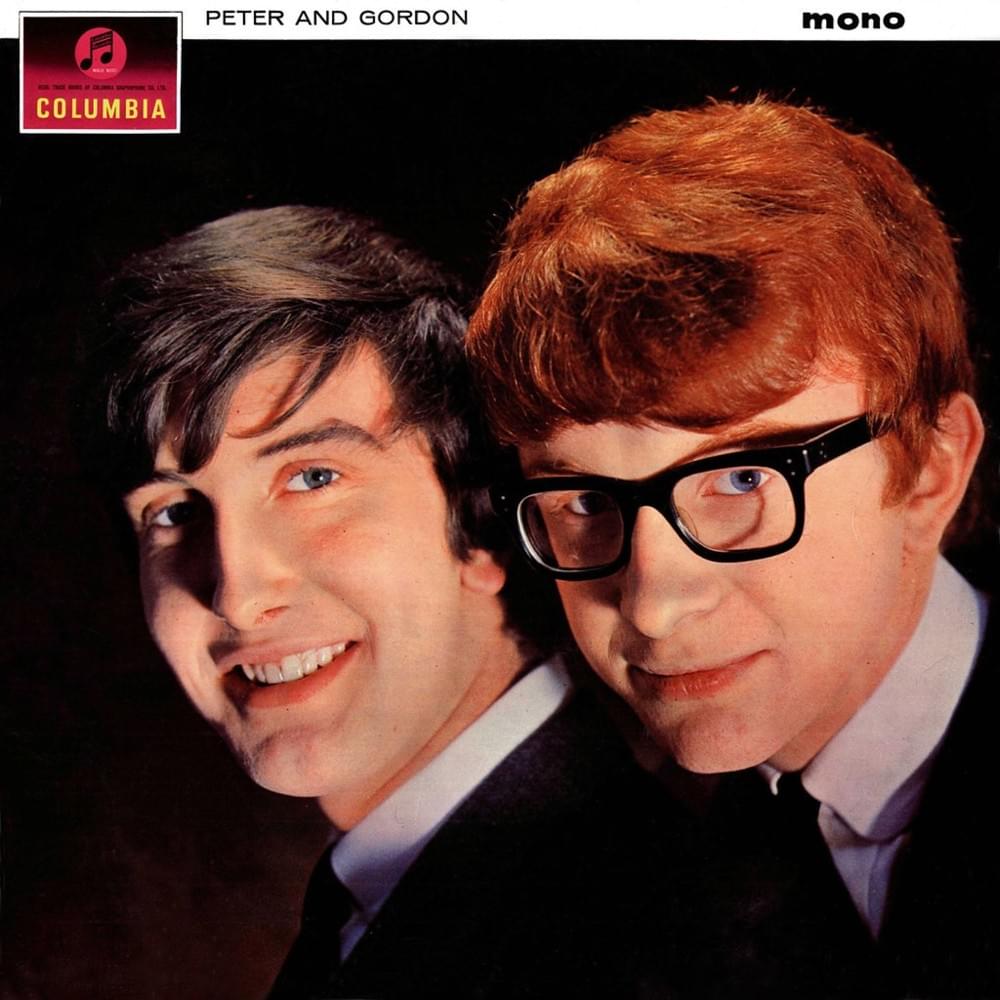

This was Peter and Gordon’s debut single in 1964, written by Paul McCartney (credited Lennon–McCartney), and first released on Columbia in the UK, then Capitol in the US. It ascended quickly and cleanly, an emblem of the British Invasion’s softer front. Produced by Norman Newell, and—many sources note—arranged by Geoff Love, it later anchored the duo’s debut long-player: in Britain titled simply “Peter and Gordon,” in North America retitled after the hit. Context matters here: the duo was emerging just as Liverpool and London were redrawing the pop map, and Peter Asher’s household proximity to McCartney has been told and retold, but what still surprises is how naturally this song sits in their voices, as if written from inside their harmonic instincts. The song may have come from a Beatle, but Peter and Gordon gave it its particular pulse.

What makes it breathe is restraint. The opening verse doesn’t push; it leans. The double-tracked vocal floats above a small room band—light drums, crisp acoustic strums, and a bass line that chooses support over spectacle. If there is a secret ingredient, it’s the harmony placement. Rather than stack to the sky, the blend stays in a narrow register, creating intimacy without claustrophobia. Plate reverb adds a silvery halo, but the producers avoid syrup. You can all but picture the mics at EMI Studios, London: ribbons or condensers set close enough to catch breath and consonant clicks, with just enough room tone to keep everything human.

There’s something boyish yet poised in the verses. The melody tends to rise at the end of each phrase as if it’s asking permission, and then resolves in a way that feels like answering your own question. On paper, the chords are straightforward; in practice, the performance makes them feel inevitable. It’s a small miracle of economy: the arrangement gives each element space. When a tidy instrumental figure enters—some accounts cite a light organ color; at minimum, there’s a timbral lift in the midrange—the track never loses its center. Dynamics crest subtly into the chorus; nothing shouts.

As a piece of music, “A World Without Love” measures emotion in teaspoons rather than ladles. The drums are rarely more than a metronomic heartbeat. The acoustic guitar provides the scaffolding, its attack soft enough that the strum isn’t choppy, its sustain long enough to knit lines together. The bass is unfussy, commanding precisely because it isn’t busy. If a piano doubles anywhere, it does so like a shadow—felt more than heard. This is the art of almost nothing: the confidence to let air carry meaning.

What also keeps the record lively is the duo’s diction. Listen to how the sibilants don’t smear, and the vowels stay round—an engineering decision as much as a vocal one. The producers avoid over-equalizing high frequencies; the reverb tail sits behind the vocal like a sheer curtain rather than a fog. That means you can track their phrasing choices bar by bar: a scooped syllable here, a straight tone there, then the tiniest vibrato at a cadence. The song communicates not by belting but by clarity.

Of course, the lineage is part of the intrigue. McCartney reportedly drafted the core when he was a teenager, and the Beatles never cut it officially. You can hear why: it belongs to a different dramatic scale. It leans toward poised parlor pop rather than stage-lit rock ’n’ roll. That distinction turns out to be a strength for Peter and Gordon. Their talents—pliant harmonies, polite intensity—fit the composition like a tailored suit. It’s not a coincidence that the track rose to the top both in the UK and in America; it made yearning portable, something you could hum on a bus.

The 1964 timing adds another layer. The charts were not just a scoreboard but a conversation among friends. The Beatles, The Searchers, The Dave Clark Five—across singles and B-sides, the language was jangly guitars, handclaps, and romantic telegraphs. In that chorus of bright declarations, “A World Without Love” threaded modesty. The title suggests bleakness, but the sound suggests careful optimism. The record refuses melodrama even when it voices private ache. In a year that often equated volume with victory, that choice reads like quiet rebellion.

If you pull the arrangement apart, the textures reveal a philosophy. The strummed rhythm sits up front, lightly compressed so it never spikes. Whatever keyboard color appears stays narrow, there to add weight to the center image rather than spread stereo width. The drums—snare damped, kick gentle—function like punctuation. A guitar lick might tilt upward between sections, but it’s brief, a nod rather than a wink. Producers of the era sometimes sweetened pop with strings; here, the “sweetening” resides in the voices themselves. The dynamic arc is intimate: verses like confessions, choruses like promises.

In those promises, you can hear the duo exercising judgment about what to emphasize. They never push the top of their range just to prove they can. Instead they give you a straight line with a soft landing. That’s why the final refrain still feels earned; the lyric stakes are high, but the performance trusts understatement. The mix also gives listeners agency: you are invited to lean in, to fill the margins with your own story.

“Understatement is the engine of this record: emotion whispered close enough to be undeniable.”

A few micro-stories prove how the song travels. In one, a college student in a new city tapes a paper schedule to a dorm wall and finds a used turntable by the curb. The needle is bent, the belt slips, but this song—spinning at the wrong pitch—still turns the room into a small chapel. In another, two commuters share wireless earbuds on a December train; they don’t speak, but when the second verse rises, their eyes meet—not romance, exactly, but a recognition that good songs carry strangers across the same bridge. Then there’s a middle-aged guitarist practicing in a quiet kitchen; he’s played louder music in louder rooms, yet what he admires here is the discipline—how the melody avoids spectacle and lands, unfailingly, on poise.

The record also frames the duo’s career arc. After this hit, they returned to McCartney’s cupboard more than once, yet the shadow of such an immaculate debut can be long. What’s striking is how their identity appears fully formed here: the acoustic-first sensibility, the near-choirboy blend, the preference for clarity. Listeners sometimes dismiss polite pop as less than visceral. But courtesy is not the absence of feeling; it’s the choice to let feeling arrive unforced. The success of “A World Without Love” suggests audiences in 1964 were attuned to that difference.

If you’re listening with an engineer’s ear, copy the details. The way the vocal EQ leaves a modest bump around the presence region but avoids the brittle bite that would date the track. The decision to keep the rhythm section mono-leaning, prioritizing focus over width. The mastering that resists loudness, allowing transient detail to breathe. If you upgrade your playback, you’ll notice more: the tiny room reflections around the snare, the quick fade on the final note, the tightness of the edits between takes. It’s a record that rewards attention without requiring it.

People often want to “figure out” why a song like this still works when taste and technology have migrated so far. Part of the answer is compositional—a melody that sits comfortably inside the human voice. Part is performance—a tempo that neither drags nor hurries, voices that balance earnestness and composure. And part is production—decisions that would still pass muster today. Put on high-quality speakers or a trusted pair of studio headphones and you finally catch how the harmony slides into the tonic like a returning tide. It’s not nostalgia talking; it’s craft.

Then there is the lyric angle. Even without quoting, we can say it treats isolation as a landscape and companionship as shelter. That is, frankly, timeless. Yet the record keeps the stakes at a scale anyone can inhabit. It’s an invitation, not a sermon. Many songs from the period airbrushed heartbreak; this one acknowledges doubt as a normal weather pattern, then suggests reliable shelter. That’s not naïveté; that’s wisdom from the far side of teenage years.

Imagine the track as it would appear on a shelf: the single with its complementary B-side, then the U.K. debut pressing where it sits among folk-tinged covers and breezy originals. The album (in either territory) provides the frame, but this song is the painting everyone stops to stare at. You can hear why DJs reached for it; you can hear why it crossed the Atlantic with ease. Radio favored records that spoke swiftly and left room for breath; this one does both.

If you’re a player, try laying it out at home. Strum lightly, keep the harmony tight, and resist the urge to oversell the bridge. The song teaches control: let the downbeats land like footsteps on carpet, not pavement. If you chase it on the keyboard, avoid hammering; rolled chords will do more than octaves here. You may find yourself searching for transcriptions or even sheet music just to understand why the cadences feel so inevitable. The secret is that the song’s architecture is kind to performers—it gives you rails to follow while leaving space to be yourself.

And if you’re simply a listener, this is an ideal test case for how taste matures. When you are young, you might prefer songs that announce their intentions with blare. With time, records like this become companions. They don’t shrink in the light; they seem to grow in proportion to your willingness to meet them halfway. That’s the difference between a fad and a standard. Standards survive because they perform the same quiet miracle in different rooms.

Accuracy matters, and the facts are solid: a 1964 release, a first single that climbed to No. 1 on both sides of the Atlantic, cut in London under Norman Newell’s steady hand, with arranging credit often linked to Geoff Love, and folded into the duo’s debut set. Those particulars describe a moment. But the reason we return isn’t the milestone; it’s the mood. The track holds up because it cares about proportion. In an era intoxicated with novelty, it offered humility. In a market that rewarded flash, it chose finish.

Decades later, new listeners still find their way to “A World Without Love” through compilations, algorithmic playlists, and hand-me-down LPs. However you arrive, the song asks the same thing of you: honesty. Meet it there, and the chorus will feel like a promise kept. Listen closely for how the last phrase settles without flourish, and you’ll understand the idea at the heart of the record—that tenderness can be decisive.

One more personal note. I’ve cued this track in cities that never sleep and in towns where midnight feels like a locked door. In both places it sounds like a light left on. There’s no arguing with that. In a discography that includes bigger gestures and bouncier singles, this remains the masterclass in considered feeling, in making small choices count. You don’t need a wall of sound to build a home.

Before you move on, consider one more pass with attention to the midrange blend, the patient tempo, the unshowy harmony entrances, the supportive bass. What you’ll hear isn’t just a hit—it’s a lesson in understatement, which is to say, in trust.

Listening Recommendations

– The Searchers – “Needles and Pins” — Similar soft-edged jangle and close harmonies from the same British Invasion moment.

– Chad & Jeremy – “A Summer Song” — Whisper-light duo blend that prizes poise over power.

– The Beatles – “I Should Have Known Better” — Breezy 1964 buoyancy with harmonica sparkle and relaxed momentum.

– Gerry & The Pacemakers – “Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying” — Polished, mid-’64 orchestral pop that balances ache and grace.

– The Hollies – “Just One Look” — Tight harmonies and clean arrangement, with a touch more bite.

– The Seekers – “I’ll Never Find Another You” — Folk-pop calm and luminous lead lines, arranged with similar restraint.