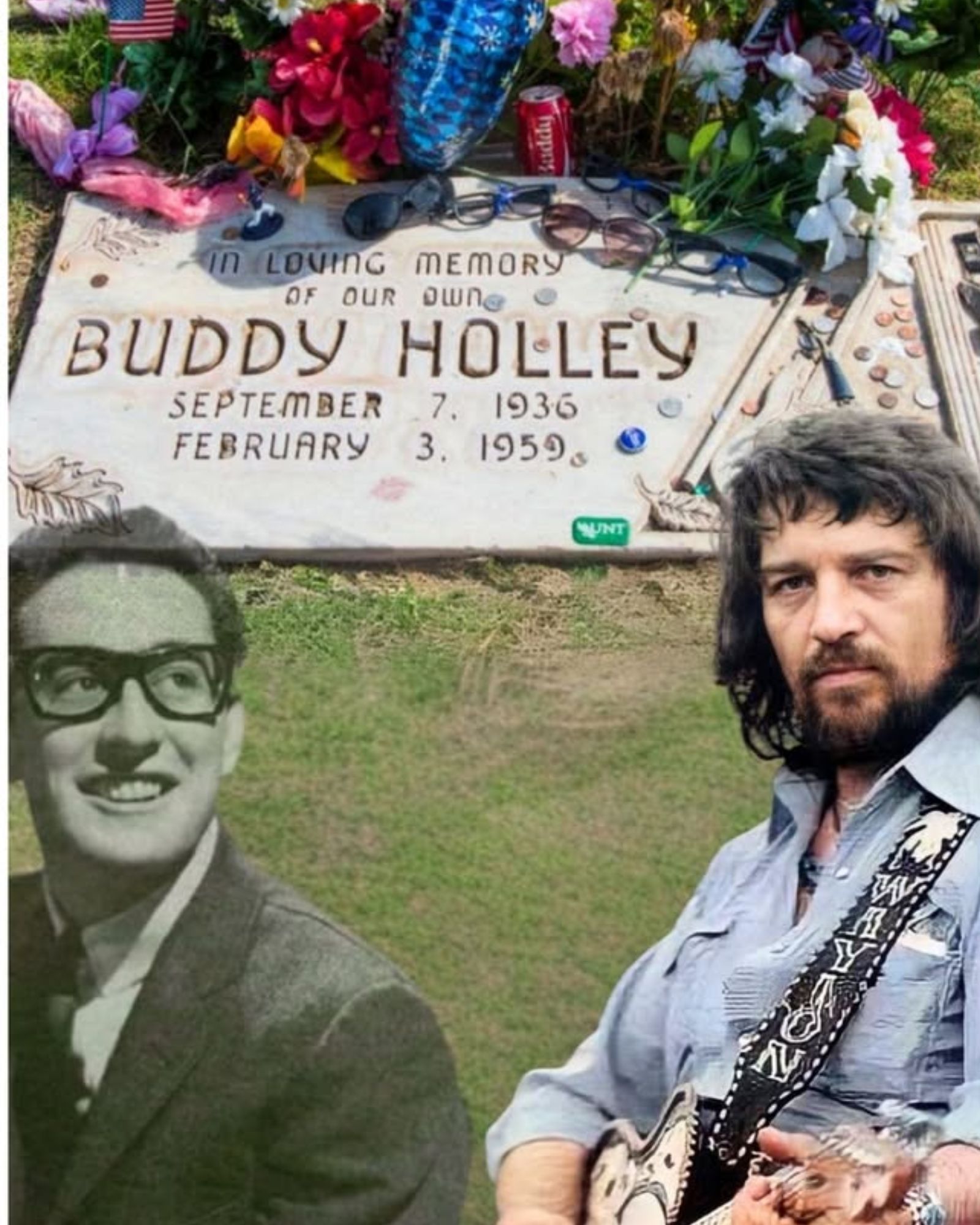

There are songs that feel like messages smuggled into the present from a room we can’t enter anymore. Waylon Jennings’ “The Stage (Stars in Heaven)” is one of those: a tender, haunted address to friends he lost on February 3, 1959, when a small Beechcraft Bonanza crashed north of Clear Lake, Iowa, carrying Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson. Jennings, then a young bassist in Holly’s band, had given his seat to the ailing Richardson; guitarist Tommy Allsup ceded his to Valens on a coin toss. History remembers the tragedy as “the day the music died,” a phrase Don McLean later fixed in popular memory. The human memory stitched into the fabric of this song is Jennings’, and the ache inside it never fully healed.

Before we go deeper into how this piece works, it helps to place it in Jennings’ discography. Although fans often encounter “The Stage (Stars in Heaven)” via later anthologies, its roots trace to the early ’60s singles and sessions that bridged Jennings’ transition from West Texas/Phoenix club hustler to Nashville force. The track sits prominently on Clovis to Phoenix: The Early Years (1995, Zu-Zazz), a compilation that gathers his rare Trend-label sides from roughly 1960–1963 and material from the JD’s era; there, “The Stage (Stars in Heaven)” appears as track two, just after “My Baby Walks All Over Me.” Descriptions of the set from labels and shops underline precisely that scope, and several track lists corroborate the song’s placement.

If you encounter it through a major reissue pipeline, you may find it on Phase One: The Early Years 1958–1964 (2002, UMG). Apple’s listing and AllMusic both flag the cut (4:09) as part of that anthology—an easy on-ramp for newer listeners who mostly explore catalogs on music streaming services. (If you’re auditioning the song, a pair of high-fidelity headphones will repay the attention with all the air and tape textures intact.)

The song’s authorship underscores its specificity: AllMusic credits Bill Tilghman as the composer, which aligns with collector notes and discographies attached to the early-years packages. Across those blurbs, one biographical thread recurs—Jennings shaped the track as an explicit memorial to the friends he lost that winter, sometimes extended to include Eddie Cochran, who died in a car accident the following year and whose absence haunts that entire generation of rock and country players.

The album context: memory as method

As an album, Clovis to Phoenix: The Early Years doesn’t simply collate singles; it sketches the road between the newness of 1958’s Holly-produced “Jole Blon” and the rougher-edged voice that would flower in Nashville. Label summaries emphasize its sweep from Brunswick-era cuts to the Trend singles and the hard-to-find Ramco side “My World.” Hearing “The Stage (Stars in Heaven)” in the second slot gives the set a narrative spine: after a honky-tonk opener, you’re plunged into reverie. Phase One (UMG’s 2002 overview) offers a more generalist lens but still hangs the song where it can glow; in either track list, it’s a hinge—memory pausing the forward momentum to watch ghosts walk on.

A contemporary reviewer caught its tone plainly: Country Standard Time called it a “maudlin tribute” that recounts the night the music dimmed for Jennings personally. “Maudlin” can read pejoratively, but here it names something true in the vocal: the quiver isn’t a studio trick; it’s the sound of a young man holding eye contact with loss.

How it sounds: the tools of reverence

What makes this piece of music move is how modest its toolbox is. The arrangement centers on clean electric guitar arpeggios and/or gently strummed acoustic patterns, a restrained rhythm section—soft snare, spare bass—and a small halo of backing voices that enter like a congregation responding to a eulogy. Where some early-’60s country sides were drenched in strings, this one breathes; its reverb is chapel-quiet rather than canyon-wide. You’ll also hear the subtle room bloom that early Trend/JD’s-era recordings carry—nearfield mics catching the singer’s breath as much as the note. The harmony parts rarely crowd Jennings; they tuck just behind the lead line, letting him line-draw the narrative.

If you listen carefully at phrase ends, the vocal release often carries a half-sobbed fall, a timbral gesture Jennings would revisit across his career. In other words, the vocal is an instrument here, and the band leaves it space. It’s the opposite of a showboat number: a steady four underfoot, quasi-hymnal chord motion atop it, and text first. In later remasters, the top end is a hair glassy compared with the mid-richness of the transfers you’ll find on vinyl pressings; either way, the focus is right where it belongs—on the singer speaking to the departed.

What it says: a stage beyond compare

Lyrically, “The Stage (Stars in Heaven)” imagines a celestial venue where the friends we lost are still on the bill, the stage a kind of border crossing between here and a hall of memory. Fan-archivist transcripts preserve the image patterns: a “stage beyond compare,” “stars assembled there,” and the comfort of songs “we all loved so.” There’s no moral or sermon—only the survivor’s wish that the music carries on someplace kinder than a black-ice runway in rural Iowa.

Jennings’ biography keeps folding back into the song. The crash’s logistics are well-worn history now, but tiny details never lose their sting: Richardson took Jennings’ seat because he had the flu; Valens and Allsup settled the last seat with a coin toss at the Surf Ballroom; minutes later the plane fell out of the night sky. The basic outline is corroborated across multiple reliable sources, including History.com and Wikipedia’s long-maintained entry, as well as the National Park Service’s Surf Ballroom site, which preserves the tour’s local memory.

One reason the performance feels so naked is that Jennings carried survivor’s guilt for decades. The Country Music Hall of Fame’s biographical entry even recalls the gallows-humor exchange—Holly telling Waylon he hoped the bus froze, Jennings tossing back the now-awful retort. Whether you take that apocrypha as literally true or not, the weight of it is audible every time the chorus comes around.

Where (and how) to hear it

If you prefer to hear the track in its singles-era context, hunt down Clovis to Phoenix: The Early Years; retailer/label listings make clear that “The Stage (Stars in Heaven)” is integral to that story, not an afterthought. Collectors will also note the 1963 Trend single pairing “My Baby Walks All Over Me” with “The Stage,” a useful breadcrumb in the song’s physical media trail. If you want modern convenience and reliable metadata, Phase One: The Early Years 1958–1964 is on the major platforms—and tagging there nails the four-minute runtime that circulates today.

Whichever path you choose, this is one of those recordings that rewards a quiet room. Dial down the lights, and let that room-tone hush be part of the arrangement. On many masters you can hear a faint halo around the vocal whenever Jennings leans back from the mic; it makes the imagined “stage” feel like it’s just across the dark.

Why it endures

Country music has never been allergic to mourning, but Jennings’ cut threads an unusually delicate needle: it’s both elegy and self-interrogation. He isn’t just singing about greats; he’s singing to his friends, and to the piece of himself that never got off that tour bus. The melody keeps things simple—mid-range, syllabically aligned to the cadence of plain speech—so the words can carry without rhetorical fog. If you come to Jennings through the late-’70s outlaw records, this track may surprise you: it’s gentler, almost devotional. But the spine—the insistence on telling the truth about what a night did to a man—runs straight to Honky Tonk Heroes, Dreaming My Dreams, and Waylon & Willie. It’s all of a piece.

The song also functions as a witness stand for an era. In the late ’50s and early ’60s, the lines between rockabilly, country, and pop balladry were porous; Holly, Cochran, and Jennings all walked those roads. When you hear “The Stage (Stars in Heaven),” you hear that borderland: country phrasing, rock-school guitar voicings, a pop sense of refrain. That fusion is why the track still lands for listeners raised on playlists rather than radio formats.

For listeners who love context—and more music

If this elegy speaks to you, a few adjacent tracks deepen the portrait:

-

Tommy Dee — “Three Stars.” Written and released in 1959 within weeks of the crash, it’s the ur-tribute—raw and direct, later recorded in a devastating version by Eddie Cochran. It’s a major historical counterpart to Jennings’ song.

-

Waylon Jennings — “Best Friends of Mine.” Cut four decades later on Closing In on the Fire (1998), Jennings looks back with a veteran’s candor and salutes Buddy Holly by name; the album notes and write-ups explicitly call it a tribute.

-

Don McLean — “American Pie.” No list would be complete without the myth-making ballad that enshrined “the day the music died” in the popular lexicon; it’s the cultural echo to which Jennings supplies the personal timbre.

These don’t replace “The Stage (Stars in Heaven)”; they frame it—one immediate reaction from 1959, one from Jennings himself at career’s end, and one from the broader pop imagination.

A few final listening notes

Because the track lives in multiple anthologies, minor mix differences and transfer philosophies exist between releases. The Zu-Zazz set often reads slightly warmer, emphasizing midrange body; UMG’s Phase One has the clarity and level consistency you’d expect from a 2000s archival pass. If you’re auditioning across catalogs on music streaming services, don’t be surprised if you notice a small swing in perceived loudness and reverb tails—both are artifacts of source and mastering, not creative revision.

And if you’re the type who searches for piece of music, album, guitar, piano when you want to dive deeper than a hit single, this track is a powerful reminder that a catalog’s early corners can contain the purest declarations. “The Stage (Stars in Heaven)” is quiet work, but its afterglow is long.

Credits & sources for deeper reading/listening:

Song/composer listing and “appears on” data via AllMusic; composer credited to Bill Tilghman.

Album placements and track listings via Bear Family/Zu-Zazz descriptions, Amazon and Discogs entries for Clovis to Phoenix: The Early Years.

2002 anthology presence and runtime via Apple Music and AllMusic’s Phase One page.

Historical crash context and the Jennings/seat-swap details via History.com, Wikipedia, and the NPS Surf Ballroom page.

Contemporary characterization of the track’s memorial tone via Country Standard Time’s review.

Adjacent recommendations documented via Wikipedia for “Three Stars” and Wikipedia/album notes for Closing In on the Fire.

If you start anywhere, start with the second track on Clovis to Phoenix. From there, let Jennings walk you onto that imagined stage, one friend at a time.