I remember the first time I heard Alan Jackson sing this on radio—late night, static curling at the edges of the signal, a voice so calm it felt like a hand on the shoulder. No grand preface, no preamble, just that clean acoustic bed and a melody that took two steps forward and one step inward. In a season of noise and certainty, the song asked questions. That was its radical act.

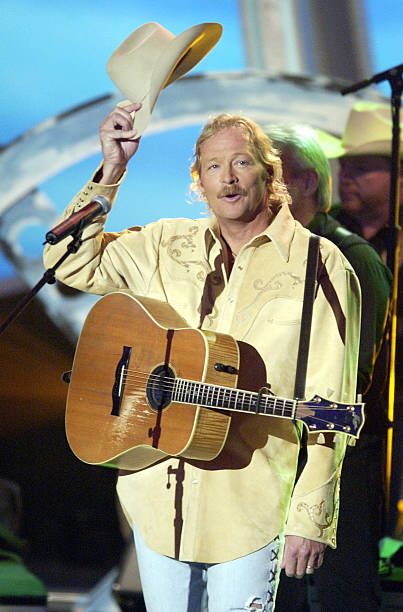

“Where Were You (When the World Stopped Turning)” arrived in 2001 as a single from Jackson’s Arista Nashville run, produced by his longtime collaborator Keith Stegall and later placed on the 2002 album “Drive.” By then, Jackson was already a pillar of ‘90s and early-2000s country—neotraditional but modern, a keeper of the flame who understood how to write for the dance floor and the front porch. This track, though, moved onto a different register. It wasn’t topical in the way protest songs or anthems are topical; it was personal, respectful, and resistant to easy slogans. He reportedly wrote it quickly, and yet it landed with the weight of something that had taken a lifetime to learn: humility before pain.

The arrangement is almost transparent. Listen closely and you hear air—room tone, space for the phrases to breathe. The drums are lightly brushed, more heartbeat than backbeat. A soft electric and acoustic blend carries the harmony with unforced grace; steel lines arc in small sighs, like a kind of musical inhalation. There’s a restraint to the mix, a decision to keep the singer’s proximity intimate, the reverb tail short enough to feel present but long enough to suggest a church-like hush. The instrumentation does not compete; it cradles.

This is where Jackson’s vocal choices matter. He refuses melodrama. Instead of leaning on vibrato to telegraph emotion, he lets syllables hang on the edge—sometimes slightly behind the beat, sometimes leaning into the downstroke as if to steady himself. He lands the hooks not by belting, but by framing the chorus as a confession. His phrasing is careful; you can hear how each line confronts the unsayable without attempting to solve it. He does not raise his voice; he widens his silence.

From a craft perspective, the melody is simple enough to feel remembered the first time you hear it. It arcs gently, like an embrace that loosens rather than tightens. The chord movement avoids grand modulations or “triumph” cues. It sits in that rare place between folk plainness and country polish. A single strum shapes the contour of a line; a quiet slide answers it. The texture builds in tender increments—by the second chorus, you feel fuller, not louder. That difference matters.

This piece of music is also a masterclass in perspective. Rather than telling the listener what to feel, it asks where they were, what they were doing, who they called. Those questions invite memory to fill the gaps, which is why so many listeners heard their own stories echoing back at them. The lyric avoids policy or blame; it chooses the daily objects of life—shoes by the door, coffee on the counter, a classroom, a church pew. It understands that grief often arrives through routine, not grand pronouncement.

Album context matters here. “Drive” would become one of Jackson’s defining releases, bridging barroom ease and reflective adulthood. Placing this single within that album’s sequence was a subtle act of curation: the record celebrates family, vintage cars, and the shorthand of rural life; the song gives that world a moment of reckoning. It turns nostalgia into moral attention. The production continuity—the same players, the same ears from Stegall—helped fold a national lament into the fabric of Jackson’s familiar sonic home.

The timbral choices are modest and exact. You can hear the wood of the acoustic instrument—a rounded attack, dry sustain. The electric colors are milk-glass clean, with a small, respectful shimmer that could as easily be from a chorus pedal as from the console’s tasteful sheen. The bass sits low and centered, never crowding the vocal. If you listen on decent studio headphones, the mix reveals a light stereo field: a rhythm element staked center-left, a counter-figure panned just enough to open the image without calling attention to itself. And inside this pocket, Jackson’s baritone rides steady, a lantern held chest-high.

It is a country ballad in clothing, yes, but it’s also a quiet documentary of human reaction. When he names the first responders and the simple gestures people made—praying, calling family, holding hands—he stakes the song’s hope not in ideology but in decency. That decision, more than any production flourish, is why the track aged with grace. Many sources note that the song topped the country charts and crossed into the pop listings; it also earned Jackson major awards, including honors from the CMAs and Grammys. But the bigger achievement is durability. It remained on playlists not because it promised resolution, but because it promised presence.

One of the most moving aspects is how the music refuses catharsis until it’s earned. There’s a gentle lift into the chorus, but it never erupts. The dynamic arc feels like walking into a sanctuary rather than onto a stage. The piano arrives not as a lead instrument but as a cushion, a small halo around the vocal as the lyric draws its circle wider. If the word “prayer” is overused in music criticism, here the analogy is not a metaphor; it is a method. The song prays by asking, not declaring.

I think about three small moments when the song found people and held them.

First vignette: a truck stop on a winter night, TVs still playing replays of the same footage, a handful of travelers picking at pie they didn’t want. The waitress turns the radio up slightly when the first verse comes on. No one says a word. A man in a work jacket stares into his coffee, and by the bridge he’s rubbed a circle into the condensation on the glass. He’s not crying, not exactly. He’s remembering where he was when his phone wouldn’t stop ringing.

Second vignette: a high-school classroom, years later. The teacher has a lesson plan about media and memory. She plays the song to spark discussion. Half the students didn’t exist in 2001, but you can see them thinking about their own first big news story—the one that shifted the room’s temperature at home. They’re quiet, attentive. The guitar figure feels like a thread they follow across a decade they never lived.

Third vignette: a small-town ceremony. A volunteer firehouse dedicates a plaque. It’s warm out, microphone squealing every few minutes. Someone queues up Jackson’s song from a phone plugged into a modest PA. The moment doesn’t swell; it steadies. The chorus lands like a communal breath.

“Great songs don’t end; they create a space you can step back into, again and again, with more of yourself each time.”

What also gives the track its power is the refusal to over-arrange. There’s no sweeping string section demanding tears. The emotional center is the voice, the measured tempo, the lyric’s hospitality. And yet the details are meticulous: the way the background instruments lean ever so slightly into the downbeat of the final chorus; the faint shimmer on the high end, giving the edges of the acoustic its outline; the compression just tight enough to keep the vocal forward without squeezing the life out of it. This is an engineer’s and producer’s humility in service of a singer’s clarity.

Because the song is so straightforward, revisiting it today can feel like rediscovering a keystone in modern country’s cathedral. The early 2000s carried plenty of chest-thumping responses to catastrophe. Jackson chose something else: a local inventory of feelings so specific they turned universal. That’s an old folk trick, but here it sounds renewed.

If you are a musician looking to learn it, you’ll find the structure approachable, but the performance demands balance: singing with conviction that never curdles into certainty. The melodic contour rewards anyone doing their own arrangement—church soloist, open-mic regular, or family gathering. You start to notice how the lyric places nouns like stones across a creek so the listener can cross without getting wet.

Even the mix invites careful listening. The frequencies around the vocal’s upper mids—where consonants live—are smoothed without dulling the articulation. The plucked notes decay at a pace that reads “room,” not “plug-in.” There’s a small downshift before each chorus, a collective easing into the refrain. That’s how you design dynamics without shouting. A single tambourine or shaker might ghost by—so soft you feel the rhythm more than you hear it. This is craftsmanship that resists the urge to be noticed.

As for its place in Jackson’s career arc, the song is a pivot and a confirmation. He had already proven himself a hit-maker and a steward of country tradition. With this track, he also became a public mourner, a role he handled with unusual care. On “Drive,” nestled among songs about family and the literal cars of the title track, “Where Were You (When the World Stopped Turning)” is the quiet room at the back of the house, a space where the party steps lightly and removes its hat. The album benefits from that room’s gravity. And the culture, for a time, did too.

I also think the song teaches a small lesson in musical ethics. There’s a way to approach tragedy with craft that does not exploit it. Jackson’s lyric refrains from instruction; it leans into description. It names everyday acts—giving blood, praying, volunteering—without turning them into points scored. In doing so, it acknowledges that the listener’s experience might not match the singer’s. That’s hospitality. That’s why people played it at ceremonies, in living rooms, on patrol bases, and in halls of remembrance.

On a practical note, anyone trying to learn it will find chord charts circulating widely; for those interested in the notational side, searching for the official sheet music can help clarify the phrasing choices that keep the vocal grounded. And if you want to catch the tiny production cues—the place where the bass breathes, the faint stereo air around the acoustic bed—give it a late-night listen on capable studio headphones. You will hear how the mix holds you near, how the decay of the final line doesn’t resolve so much as rest.

Simplicity is often mistaken for ease. It’s hard to sing plain; it’s hard to write without armor. Jackson managed both. The result is a song that neither shouts nor whispers; it speaks. That may be why, decades on, it still accompanies moments that ask for dignity. Not many records volunteer for that duty and keep volunteering.

In the end, the track accomplishes something deceptively rare: it turns the solitary act of listening into a small community, each person answering the central question in their own way. And then, for four minutes, we stand together in the same quiet room. When the last chord fades, nothing is solved—but something has been witnessed. That’s enough. And it’s more than enough to press play again.

Listening Recommendations

-

“Travelin’ Soldier” – The Chicks

A spare narrative that leans on acoustic intimacy and everyday detail to carry heavy emotion. -

“If You’re Reading This” – Tim McGraw

A letter-from-the-front structure that pairs restraint with a resonant, ceremonial tenderness. -

“I Drive Your Truck” – Lee Brice

A personal-grief portrait rendered through objects and routine, with a hushed, modern-country arrangement. -

“The House That Built Me” – Miranda Lambert

Memory as architecture; a soft arrangement lets the vocal hold the center without spectacle. -

“Go Rest High on That Mountain” – Vince Gill

A gospel-tinged meditation whose harmonies lift grief into communal space without losing humility. -

“Just a Dream” – Carrie Underwood

A story-song of loss that balances orchestral lift with carefully measured vocal power.