A Portrait of Longing That Refuses to Fade

There are songs that entertain, songs that comfort, and then there are songs that quietly rearrange the emotional furniture of your life. “Angel from Montgomery” belongs to the latter category—a composition so deceptively simple, yet so devastatingly honest, that it has become part of America’s emotional vocabulary. Written and first recorded by John Prine for his 1971 self-titled debut album, the song did not storm the charts in a blaze of commercial triumph. Instead, it did something far more enduring: it burrowed into the collective conscience of listeners who recognized themselves in its weary lines.

That debut album, John Prine, marked the arrival of a songwriter with a rare gift for empathy and observation. It entered the Billboard 200, signaling that something special had arrived in the folk and country-rock landscape. Yet it wasn’t chart dominance that made “Angel from Montgomery” immortal. It was resonance.

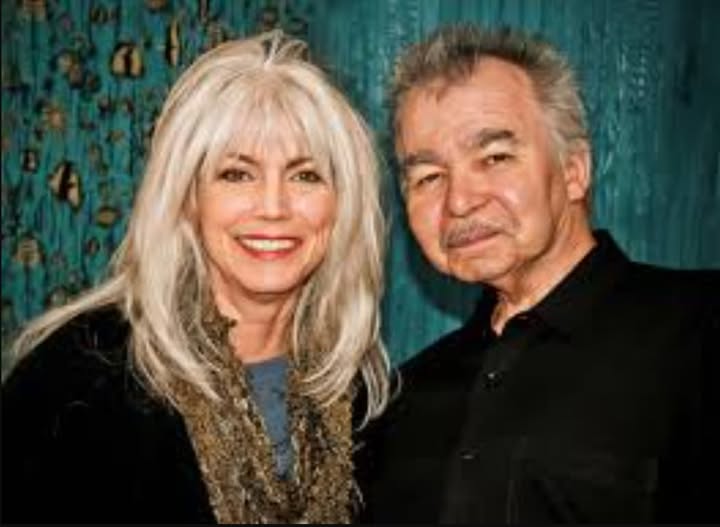

In 1974, Bonnie Raitt recorded her now-classic interpretation for the album Streetlights, introducing the song to a much wider audience. Raitt’s smoky, soulful delivery brought the character’s quiet desperation into sharper relief, cementing the track as a modern American standard. Decades later, the song would continue to evolve, most poignantly in live and studio performances featuring Prine alongside Emmylou Harris—a collaboration that transformed the piece into something like a spiritual dialogue.

The Birth of a Kitchen-Sink Masterpiece

The origins of “Angel from Montgomery” are almost mythically modest. At the time, Prine was a former mailman from Maywood, Illinois, known for scribbling lyrics while walking his postal route. A friend had suggested he write another song about older people, referencing his earlier compassionate ballad “Hello in There.” Prine initially resisted the idea, feeling he had already explored that terrain. But then came an image—simple, vivid, heartbreaking: a middle-aged woman standing at her kitchen sink, hands submerged in soapy water, staring out the window and imagining escape.

That image became the seed of the song.

Prine once noted that he realized this woman “felt older than she is.” That single insight unlocked a flood of lyrical clarity. The opening lines remain among the most arresting in American songwriting:

“I am an old woman, named after my mother

My old man is another child that’s grown old.”

In two lines, Prine sketches an entire life. There’s generational repetition, disappointment, emotional stagnation. The husband is not a partner but “another child”—a burden rather than a companion. The domestic space becomes less a sanctuary than a quiet prison.

Prine chose Montgomery, Alabama, as the setting—likely a subtle homage to Hank Williams, one of his musical heroes. The Southern backdrop lends the song a humid melancholy, a sense of faded romance lingering like heat in the air. The titular “angel” becomes both literal and metaphorical: a symbol of rescue, of transcendence, of divine interruption in a life dulled by routine.

The Meaning Beneath the Melody

What makes “Angel from Montgomery” extraordinary is not dramatic storytelling but emotional precision. The song captures a particular ache: the realization that life has narrowed, that possibility has quietly evaporated.

The narrator doesn’t rage. She doesn’t accuse. Instead, she confesses. She speaks of kitchen flies, endless routine, and the way dreams fade into the background hum of domestic life. The “old rodeo” poster hanging on her wall becomes a symbol of lost vitality—a reminder of youth, of movement, of a time when she might have believed in wide-open roads and free-ramblin’ cowboys.

The angel she longs for is not necessarily a lover. It’s not even specifically a person. It is intervention. It is the miraculous breaking of monotony. It is hope arriving unannounced.

In that sense, the song transcends gender. Though written from a woman’s perspective, its emotional core speaks to anyone who has woken up one day and wondered how their life became smaller than their dreams. That universality explains why the song has endured across generations, genres, and voices.