The needle drops. There’s no fade-in, no hesitant intro—just an instant, brass-knuckled jolt of rhythm. A soaring, familiar fanfare of horns bursts forth, a three-second declaration of intent that, legendarily, was lifted from the theme to The Magnificent Seven. It is a sound that cuts through the atmosphere of any room, demanding an immediate response. “Do ya like good music, huh?” Arthur Conley challenges, his voice a coiled spring of youthful exuberance and seasoned soul grit.

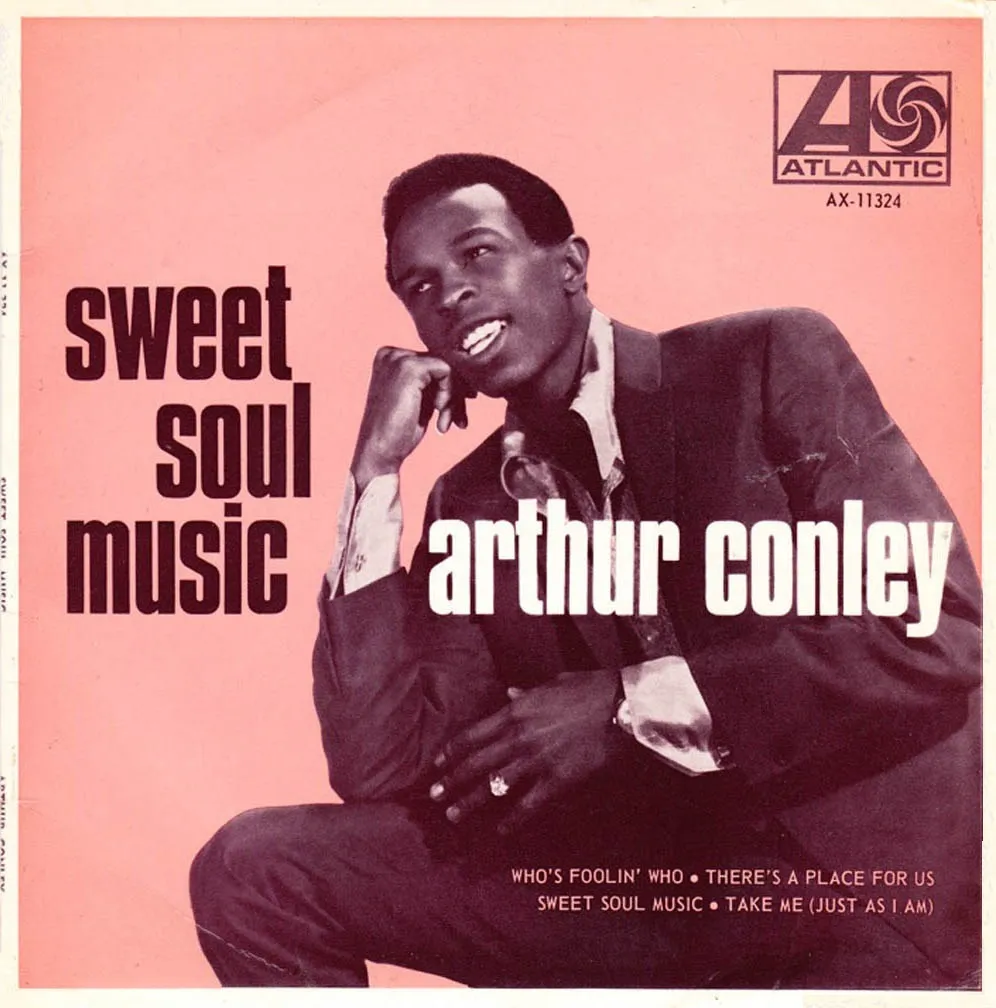

This is the sound of “Sweet Soul Music,” released in March 1967 on the Atco label. It is not just a hit record; it is a musical manifesto, a historical document, and one of the most perfectly distilled examples of Southern Soul ever committed to tape. For a long time, I carried this piece of music with me as a road trip soundtrack, a shot of pure adrenaline for the long haul. Now, listening in the stillness of my home audio setup, I hear the layered complexity that powers its sheer, immediate joy.

The Protégé and The Prophet

To understand “Sweet Soul Music,” you must first understand its context, both for Arthur Conley and the man who stood behind the glass: Otis Redding. By 1967, Arthur Conley was a young Atlanta singer with a powerful, graceful voice, but still searching for his breakthrough. His fortunes changed entirely when Redding, already the established King of Soul, heard Conley’s earlier work and took him on as a protégé, signing him to his Jotis label.

The genesis of this career-defining track is a beautiful piece of soul music lore. Conley and Redding co-wrote the song, reworking the bones of an obscure, posthumously released Sam Cooke track called “Yeah Man.” The finished product became Arthur Conley’s debut album on Atco (distributed via Fame Records) and his career high-water mark, soaring to No. 2 on both the US Pop and R&B charts, and reaching the UK Top 10. Tragically, this triumph would precede Redding’s untimely death by only a few months.

The song is a brilliant vehicle for Conley, a twenty-one-year-old singer suddenly entrusted with carrying the torch. Its structure is a celebration of the genre, a roll call of soul legends that places Conley squarely within a powerful lineage. When he sings, “Spotlight on Lou Rawls, y’all, don’t he look tall, y’all,” he is not just reciting names; he is weaving a tapestry of shared cultural adoration.

Inside the Engine Room: FAME and The Sound

The recording took place at FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, and the sound of that legendary room is palpable in every scorching note. This is not the clean, clinical sound of pop; this is the sound of instruments battling for space, breathing together, and reaching a spontaneous, fiery consensus.

The core rhythm section, the foundation of the ‘Muscle Shoals Sound,’ delivers a groove of staggering simplicity and power. Roger Hawkins’s drums are dry, mic’d close, with a sharp, cutting crack on the snare that drives the tempo relentlessly forward. David Hood’s bass is fat and warm, playing not just the root notes, but a melodic counter-rhythm that locks in tight with the drums.

Over this bedrock, the brass section—likely Memphis or Muscle Shoals horns—is the song’s signature element. They deliver the iconic, recurring fanfare with a unified, piercing attack, contrasting perfectly with Conley’s high-tenor urgency. The interplay between the horns and Conley’s voice is a masterclass in call-and-response.

The unsung hero of the arrangement is often the sparse, yet essential, use of the chordal instruments. A clean, biting electric guitar (likely Jimmy Johnson) plays a simple, repeated riff that interlocks with the bass line, providing texture rather than melody. The piano, a bright, gospel-inflected instrument, pops up only in short, joyous bursts, often just to punctuate the end of a line or drop a handful of high notes into the mix, adding a necessary harmonic lift without cluttering the rhythm.

“‘Sweet Soul Music’ is not a reflection on soul; it is the physical sound of soul demanding to be heard, demanding to be danced to.”

The role of Otis Redding as producer cannot be overstated. He clearly understood that Conley’s voice, which possesses an almost gospel-like purity mixed with an athletic, powerful attack, needed a stripped-down, live sound to shine. The short runtime (just over two minutes) reflects the single-minded focus of the production: maximum impact, zero waste. Every element—the backing vocals chanting “Oh yeah! Oh yeah!” and the famous name-checking sequence—is designed for instant, cathartic release.

A Legacy of Joy

The sheer velocity of the track is what makes it timeless. There’s a vignette that plays in my head whenever I hear the opening horn blast: a dusty, late-night DJ pulling the 45 from its sleeve, slapping it onto the turntable, and watching the entire club floor instantly erupt. This song doesn’t wait for permission; it starts the party.

When Conley sings, “Spotlight on Otis Redding now / Singin’ fa-fa-fa-fa-fa / Oh yeah, oh yeah,” the tribute is deeply personal. It’s a genuine expression of gratitude and mentorship, a snapshot of the bond between two Georgia soul men working to cement a legacy. It is a moment of communal celebration that transcends the individual artist. This kind of shared admiration—artists celebrating each other’s work—is what the soul genre, at its core, is all about.

The song’s longevity has made it a litmus test for good times, adopted by everything from movie montages to celebratory kitchen dance-offs. It’s a testament to the power of Southern Soul: music that feels both sophisticated in its rhythm and utterly primal in its emotion. The fact that generations of aspiring musicians have had to dissect this vibrant energy, whether for guitar lessons or drum practice, speaks to its foundational importance in the R&B canon. It is a moment of unfiltered, electric euphoria that Arthur Conley gave the world, a lightning strike that illuminated his brief, brilliant time in the spotlight.

Listening Recommendations: Songs of High-Octane Southern Soul

- Otis Redding – “Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa (Sad Song)” (1966): Cited in “Sweet Soul Music,” this track shares a similar infectious energy and the raw, Muscle Shoals/Stax-style production that defined the era.

- Wilson Pickett – “Mustang Sally” (1966): Another Conley name-check and a defining piece of aggressive, horn-driven Southern Soul, recorded with the same FAME/Muscle Shoals crew.

- Sam & Dave – “Hold On, I’m Comin'” (1966): Named by Conley in the lyrics; an explosion of joyous, synchronized vocal and instrumental urgency.

- James Brown – “Cold Sweat” (1967): The “King of them all,” Brown’s contemporaneous hit features a similar rhythmic intensity but focuses more on a complex, driving funk groove rather than a melodic hook.

- Aretha Franklin – “Respect” (1967): Shares the undeniable, empowering confidence and full-throttle delivery that characterized the peak Atlantic/Southern Soul sound of the same year.

- Joe Tex – “Skinny Legs and All” (1967): Features a similar talking-and-singing vocal style and raw energy, demonstrating the communicative power of soul in the mid-1960s.