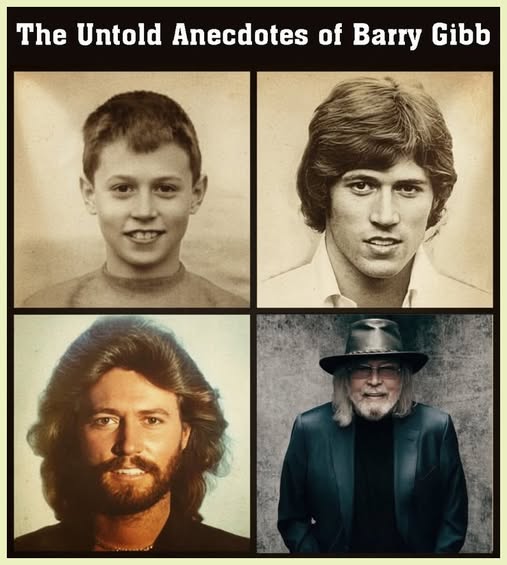

Few figures in popular music embody endurance, reinvention, and quiet resilience quite like Barry Gibb. As the creative backbone of the Bee Gees, Gibb’s career spans more than six decades—an extraordinary journey that stretches from post-war England to global superstardom, from analog studios to electrified stadiums, and from near anonymity to cultural immortality. While chart records and awards often dominate discussions of the Bee Gees, it is the lesser-known anecdotes—the moments of risk, hardship, and persistence—that reveal the true architecture of Barry Gibb’s legacy.

One such defining moment unfolded on a rain-soaked night in Jakarta during the 1960s, an episode that has since taken on almost mythic proportions. Thousands of spectators filled the stadium under heightened political tension. Armed guards surrounded the venue. A full orchestra stood ready—until torrential rain flooded the stage, rendering electrical instruments useless. Faced with real danger, the band made a decision that would crystallize their professionalism: they stepped back from the microphones, dismissed most of the orchestra, and performed using only two violins to support their voices. It was not spectacle that carried the night—it was discipline, harmony, and nerve.

That moment did not arise by accident. It was the product of a musical foundation laid decades earlier, beginning in a modest bedroom in England.

A Guitar, a Bed, and the Spark of a Lifelong Obsession

In the early 1950s, a nine-year-old Barry Gibb sat on his bed holding a small guitar—an instrument that would quietly shape his destiny. A neighbor, recently returned from Hawaii, introduced him to open tunings and slide techniques, methods rarely associated with British pop musicians at the time. These techniques, more common in American country and folk traditions, planted the seeds for Barry’s later experimentation with texture and harmony.

Equally influential were the records spinning endlessly in Barry’s youth. At a local café, a battered jukebox played Everly Brothers singles on repeat. Their seamless harmonies—rooted in bluegrass yet accessible to pop audiences—etched themselves into Barry’s musical DNA. Long before the Bee Gees became known for their signature falsetto and layered vocals, the blueprint was already forming in those early listening sessions.

A Broader World Than Most Boys Could Dream Of

Unlike many working-class families of the era, the Gibb household was not confined to a single place. International voyages carried them through the Suez Canal and as far as Sri Lanka, exposing the brothers to sounds, cultures, and stories far beyond Liverpool or Manchester. These experiences were formative. They expanded Barry’s sense of narrative and emotional scope—qualities that would later define the Bee Gees’ songwriting, which often felt more cinematic and globally minded than that of their contemporaries.

This early exposure to movement and change would later prove invaluable as the brothers navigated the volatile terrain of the international music industry.

From Speedway Dust to a Career in Motion

The Bee Gees’ first paid performance was not glamorous. It took place at a speedway track in Brisbane, Australia, where roaring motorcycles competed for attention with three young boys and a microphone. The crowd wasn’t there for music—but something about the harmonies cut through the noise. Coins began to fall onto the ground. By the end of the night, the brothers had earned five pounds, a modest sum that nonetheless carried enormous symbolic weight. Music, they realized, could be more than a hobby. It could be a future.

Around this time, chance encounters helped shape their identity. Two local figures—Bill Gates and Bill Goode, both speedway riders and radio DJs—lent their shared initials to the band’s name: the Bee Gees. It was a coincidence, but one that stuck.

Yet behind the scenes, the most crucial figure was their father. Though not a manager in the modern sense, he served as organizer, driver, adviser, and protector. From long overnight drives to recovery after car accidents, his steady presence allowed the brothers to focus on what mattered most: their craft.

Learning the Studio the Hard Way

The Bee Gees’ early recordings were forged in an era of analog limitations. Studio time was precious, equipment was unforgiving, and vocal imperfections could not be digitally erased. Harmonies had to be precise, rehearsed relentlessly, and delivered with discipline. These conditions sharpened the brothers’ vocal control and arrangement skills—skills that later allowed them to perform under extreme circumstances, such as the infamous Jakarta concert.

By the time the band began incorporating large orchestras and complex arrangements, their foundation was unshakable. The fact that they could strip everything away—leaving only two violins—and still command a stadium speaks volumes about their technical mastery.

Music Under Political Pressure

Indonesia in the 1960s was not a neutral setting for Western pop music. President Sukarno’s presence at the Jakarta stadium added political weight to an already volatile environment. Military guards surrounded the crowd. Electrical safety became a genuine concern once the stage flooded. The Bee Gees’ decision to continue performing—carefully, deliberately, without amplification—was not just a musical choice but a calculated act of survival.

In that moment, the band demonstrated a rare combination of courage and restraint. They did not push forward recklessly. They adapted.

Beyond Disco, Beyond Nostalgia

While the Bee Gees are often remembered through the prism of their disco dominance—“Saturday Night Fever,” falsetto hooks, and late-1970s chart supremacy—their legacy cannot be confined to a single era. From early hits like “New York Mining Disaster 1941” to later reinventions as songwriters and producers for other artists, the Bee Gees consistently evolved.

At the center of that evolution stood Barry Gibb, whose early exposure to unconventional guitar techniques, global travel, and disciplined harmony work allowed him to move fluidly across genres. Folk, pop, disco, adult contemporary—each transformation felt earned, not opportunistic.

A Career Built on Resilience

For music historians and audiophiles alike, the Bee Gees’ story offers a compelling case study in longevity. It is a reminder that enduring success is rarely linear. It is shaped by family dynamics, technical limitations, political uncertainty, and countless moments when quitting would have been easier than continuing.

The image of coins clinking onto dusty asphalt at a Brisbane speedway stands in stark contrast to later global triumphs—but it is precisely that contrast that gives the story its power.

The flooded stage in Jakarta remains not a symbol of catastrophe, but of professional resilience. It captures musicians who understood that circumstances change, technology fails, and environments turn hostile—but craft, preparation, and harmony endure.

Barry Gibb’s career is not merely a sequence of hits. It is a testament to what happens when talent meets persistence, and when artists choose adaptation over surrender. In that sense, the Bee Gees’ music continues to resonate—not just as sound, but as a lesson in how popular music survives, evolves, and ultimately endures.