The air in a London recording studio, circa 1967, must have been thick with the scent of ambition, valve amps, and rain-soaked coats. You can almost imagine the scene: three brothers, impossibly young and seasoned beyond their years, standing on the precipice of global fame. The red light glows. A conductor raises his baton. And from the ensuing silence, a sound emerges—not of frenetic rock and roll, but of something far more stately, melancholic, and impossibly vast.

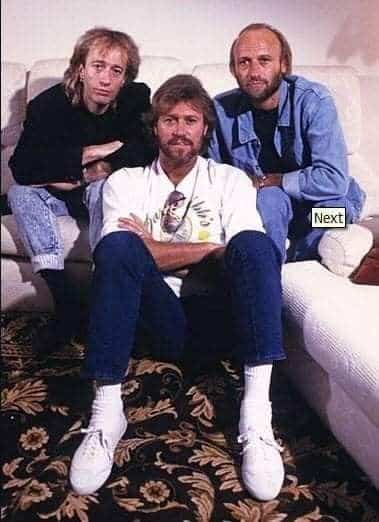

This was the world that birthed “Holiday,” a cornerstone of the Bee Gees’ international debut album, Bee Gees' 1st. Arriving in the UK from Australia, Barry, Robin, and Maurice Gibb were quickly signed by impresario Robert Stigwood, who, along with the rest of the music world, was hungry for the next Beatles. What they delivered was something else entirely. While their debut LP certainly contained flashes of Merseybeat-indebted pop, it was defined by tracks like “Holiday,” pieces that showcased a startling melodic and emotional maturity.

Working with producer Stigwood and the immense talent of arranger Bill Shepherd, the Bee Gees crafted a sound that was both of its time and strangely outside of it. “Holiday” is not a song you tap your foot to. It’s a song you inhabit. It’s a three-minute cathedral of sound, built to house a single, solitary emotion.

The genius of the track lies in its central, devastating paradox. A holiday is meant to be an escape, a joyous reprieve. But for the brothers Gibb, it becomes a metaphor for insurmountable distance and emotional exile. “You’re a holiday,” Barry sings, his voice a delicate, tremulous thread, “a million miles away.” The line is a masterpiece of pop poetry. The object of affection isn’t just distant; they are an entire, inaccessible event. A period of time, a destination, that the singer can only observe from afar.

The lyrics that follow deepen this sense of profound isolation. There are no specifics, no narrative details of a love affair gone wrong. Instead, we get a series of stark, almost existential pronouncements: “It’s a holiday, to be blind for a day,” and the chilling refrain, “Dee de-de dee dee dee dee dee dee.” This is not a failure of language but a deliberate choice. When the pain is too immense, when the distance is too great, words collapse, leaving only a mournful, wordless chant. It’s the humming of a soul adrift.

Bill Shepherd’s orchestral arrangement is not mere background dressing; it is the song’s co-protagonist. It doesn’t just support the vocal melody; it builds the emotional world the singer is lost in. The song opens with strings that sound less like a pop accompaniment and more like a chamber orchestra tuning up for a somber adagio. French horns enter, stately and sad, like fog rolling in over a deserted pier.

The rhythm section is deployed with surgical restraint. The drums are a soft, funereal tap, a heartbeat slowing to a crawl. There is a quiet, foundational piano part, but it offers little comfort, merely outlining the harmonic space where the sadness resides. The acoustic guitar is barely a whisper, a rhythmic texture more felt than heard. This sparse foundation makes the orchestral swells feel cataclysmic. When the strings climb during the chorus, it’s a wave of feeling that threatens to pull you under.

“This piece of music stands as a testament to the idea that the grandest emotions often require the most delicate touch.”

Imagine hearing this for the first time in 1967, a year saturated with psychedelia, fuzz pedals, and calls for revolution. In that context, “Holiday” was a radical statement of interiority. It was a song for the quiet moments, for the teenager staring out a rain-streaked window, feeling an ache they couldn’t yet name. It wasn’t about the party; it was about the feeling of being alone in a crowded room, watching the celebration from a million miles away.

Barry Gibb’s lead vocal is a marvel of controlled vulnerability. His signature vibrato isn’t a stylistic affectation here; it’s the sound of a voice on the verge of breaking. He never pushes, never oversells the emotion. He lets the melody and the orchestra carry the weight, his performance a fragile, human counterpoint to the instrumental grandeur. When Robin’s equally distinctive voice joins in harmony, it’s not to create a sense of unity, but to echo the loneliness, two voices singing from the same desolate space.

To truly appreciate the architecture of this song, one must listen with intent. Put on a pair of high-quality studio headphones and you can begin to dissect the layers. You can hear the subtle scrape of the bow on the cello, the breath before Barry’s vocal entrance, the cavernous reverb that gives the production its sense of scale. It’s a reminder that great pop music is also great art, meticulously crafted and deserving of deep attention. This isn’t a track to be consumed passively through a tinny laptop speaker. It’s a sonic environment to be explored.

Over the years, the Bee Gees would become chameleons, masters of disco, R&B, and soaring pop anthems. But the DNA of their balladry, the blueprint for future classics like “How Deep Is Your Love” and “Too Much Heaven,” can be found right here. “Holiday” established their credentials as songwriters of immense depth. They understood that a love song could be about the absence of love. They knew that sometimes the most powerful statement is a whisper, not a shout. The song’s composition is so strong that even today, its sheet music is a study in harmonic tension and melodic grace.

This remarkable album, Bee Gees' 1st, was the trio’s grand announcement to the world. It positioned them not as imitators, but as heirs to a tradition of sophisticated pop songwriting, placing them in the lineage of Bacharach and David or Lennon and McCartney. “Holiday” was its somber, beautiful soul.

To listen to “Holiday” today is to be reminded of the power of stillness in a relentlessly noisy world. It’s a song that doesn’t demand your attention but rather invites you into its quiet, melancholic space. It offers no resolution, no happy ending. The holiday never ends; the million miles remain. But in its shared solitude, there is a strange and profound comfort. It’s the sound of being understood, even from a great distance.

Listening Recommendations

- The Zombies – A Rose for Emily: Shares a similar baroque-pop sensibility and a deep, literary sense of melancholy.

- Scott Walker – Montague Terrace (In Blue): For those who appreciate the blend of a powerful, emotive vocal with a sweeping, cinematic orchestral arrangement.

- The Beatles – Eleanor Rigby: A direct contemporary that similarly uses a string section as a primary narrative driver to tell a story of loneliness.

- The Left Banke – Walk Away Renée: Captures the same mid-60s feeling of romantic longing, elevated by harpsichord and lush string textures.

- Roy Orbison – Crying: Another masterpiece of controlled melodrama, where a singular vocal performance builds to an almost unbearable emotional peak.

- Love – Alone Again Or: Blends folk-rock intimacy with soaring mariachi horns to create a similarly unique and unforgettable atmosphere of romantic angst.