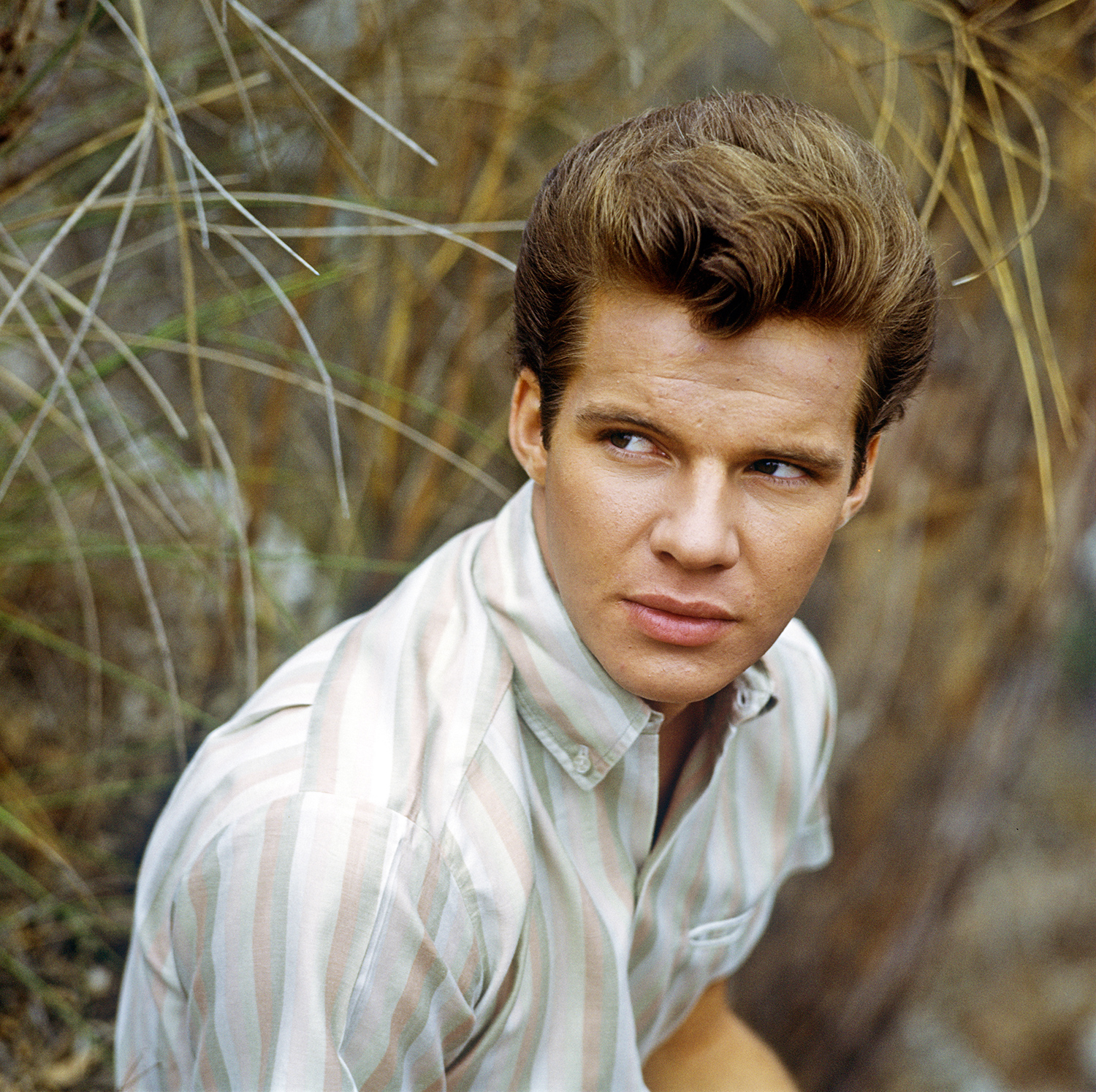

The year is 1961. The sound of rock and roll’s first wave—raw, dangerous, and often deeply regional—is transitioning. It’s becoming something shinier, more produced, and ready for the freshly scrubbed faces of a new generation of American teen idols.

In that bright, optimistic dawn, a young man named Robert Velline, known professionally as Bobby Vee, was quickly ascending the charts. His success was, in a twist of fate, tethered to a national tragedy—he was the local musician who stepped in after “The Day the Music Died.” This backstory, a quiet, respectful nod to Buddy Holly, lent a surprising depth to his otherwise clean-cut image.

Vee was signed to Liberty Records, a label that would become synonymous with his early-career hits. The creative architect steering much of that success was producer Tommy “Snuff” Garrett. Garrett’s approach was a masterclass in the Brill Building-era sound: take a simple, heartfelt melody, polish it until it gleams, and wrap it in a sophisticated, but still driving, arrangement.

“More Than I Can Say” is a perfect example of this philosophy in action. It’s a piece of music that feels instantly recognizable, yet it carries the distinct fingerprint of its era and its performers.

Echoes of the Crickets in a Polished Pop Gem

The song itself has a fascinating pedigree. It was written by Jerry Allison and Sonny Curtis, both of whom were former members of Buddy Holly’s band, The Crickets. This connection gives Vee’s version an almost spiritual lineage, a torch passed from the tragically lost rock-and-roll pioneer to the young man who briefly stood in his place.

Vee’s version, released in 1961, takes the foundational energy of the Crickets’ original and filters it through a lens of glossy, West Coast-pop refinement. The sonic landscape is built on a tightly syncopated rhythm section. The drums are bright and upfront, driving the insistent, danceable pace without ever sounding chaotic.

The arrangement is a study in controlled excitement. A robust acoustic guitar provides the rhythmic scaffolding, strumming a confident, unfaltering chord progression. Over this, a clean, melodic electric guitar weaves in subtle, short fills—brief bursts of twang and sustain that echo the rockabilly past while pushing toward the future.

Listen closely to the dynamics. Vee’s vocal delivery is earnest and youthful. He doesn’t belt the tune; instead, he communicates a deep, innocent yearning, his voice lightly layered with reverb to give it an ethereal, spacious feel.

The Subtle Sweep of Sophistication

The Brill Building sound demanded a certain maturity, a slight move away from the raw power trio format. For More Than I Can Say, this is handled beautifully through the use of an orchestrated backing. The strings are not a saccharine afterthought; they enter in the verses, a brief, soaring counter-melody that lifts the emotion without overwhelming the beat.

The low register of the piano occasionally punctuates the rhythm, adding a delightful, percussive warmth that grounds the entire track. This arrangement choice by Garrett is what separates the Liberty-era singles from simpler rock and roll: it is pop music designed for both the teenager dancing in the living room and the adult listening on their premium audio hi-fi system. The instrumental break is a compact burst of energy. It showcases the musicianship of the session players, a perfect blend of rock-and-roll propulsion and studio polish.

The emotional core of the song lies in that unforgettable, wordless hook: the “wo-wo yay-yay” chorus that serves as an emotional crescendo, a pure, wordless expression of love. It’s a moment of genius songwriting restraint, a melodic phrase so universal it doesn’t need lyrics. The chorus feels less like a manufactured hook and more like a collective sigh of inexpressible feeling.

“The emotional core of the song lies in that unforgettable, wordless hook: the ‘wo-wo yay-yay’ chorus.”

The Chart Tale: A Transatlantic Divide

The success of “More Than I Can Say” offers a fascinating case study in transatlantic pop tastes. In the United States, Vee had already scored massive hits like “Devil or Angel” and the career-defining chart-topper “Take Good Care of My Baby.” This song, while respected, was a more modest entry, reportedly climbing into the lower half of the Billboard Hot 100.

But in the United Kingdom, it was a sensation. It paired with the B-side, “Stayin’ In,” to become a double-sided hit, successfully peaking within the Top 5 on the UK Singles Chart in 1961. This European appreciation solidified Vee’s status as a bona fide international teen idol, a heartthrob whose clean image and catchy melodies resonated powerfully with British audiences looking for an American sound slightly sweeter than Elvis.

It also subtly set the stage for later artists. When Leo Sayer revived the song in 1980 for a massive global hit, the original arrangement still informed the spirit of his recording, a testament to the timeless strength of the melody forged by Allison and Curtis and polished by Vee and Garrett. Every budding singer learning to interpret an old standard should note this recording.

Legacy and Re-Listen

I was recently driving down a rainy coastal highway, the radio stubbornly locked onto an oldies station, when this album track spun into rotation. The cheerful, unyielding rhythm cut right through the grey afternoon. It hit me not as a relic, but as a vibrant photograph of a fleeting musical moment.

This is the beauty of this enduring track: it has a capacity to transport you instantly. Picture a scene: a high school sock hop, a darkened gym, the scent of popcorn and hairspray heavy in the air. The bright thrum of the guitar cuts in, the band on stage just getting started, and for a three-minute span, every young couple is lost in the moment.

It’s a feeling that translates even today. I saw a group of college students in a café, comparing notes for their piano lessons, stop mid-sentence when a cover of the song drifted from the speakers. The simple joy is infectious and undeniable, bridging generational divides with a handful of chords and a swooning vocal.

The 1961 Bobby Vee version of “More Than I Can Say” is more than just a cover; it’s a confident assertion of the new pop sound, a marriage of rock-and-roll energy and studio craftsmanship. It’s a song about a love so great that words fail—a rare and beautiful instance where the music manages to speak what the lyrics cannot. Turn it up, and let the wo-wo yay-yay do the talking.

Listening Recommendations

- “Take Good Care of My Baby” – Bobby Vee (1961): Shares the same producer, label, and heartfelt teen-pop emotional texture.

- “Travelin’ Man” – Ricky Nelson (1961): Another early 60s hit with a similarly bright, orchestrated pop-rock arrangement.

- “Happy Birthday Sweet Sixteen” – Neil Sedaka (1961): Captures the same innocent, clean-cut, Brill Building-influenced pop sentiment and sound.

- “The Night Has a Thousand Eyes” – Bobby Vee (1962): A slightly later Vee hit that perfects his use of a fast-paced, dramatic, orchestral backing.

- “It’s My Party” – Lesley Gore (1963): Features a similar bright production style but with a move towards more dramatic, mid-60s girl group-era orchestration.