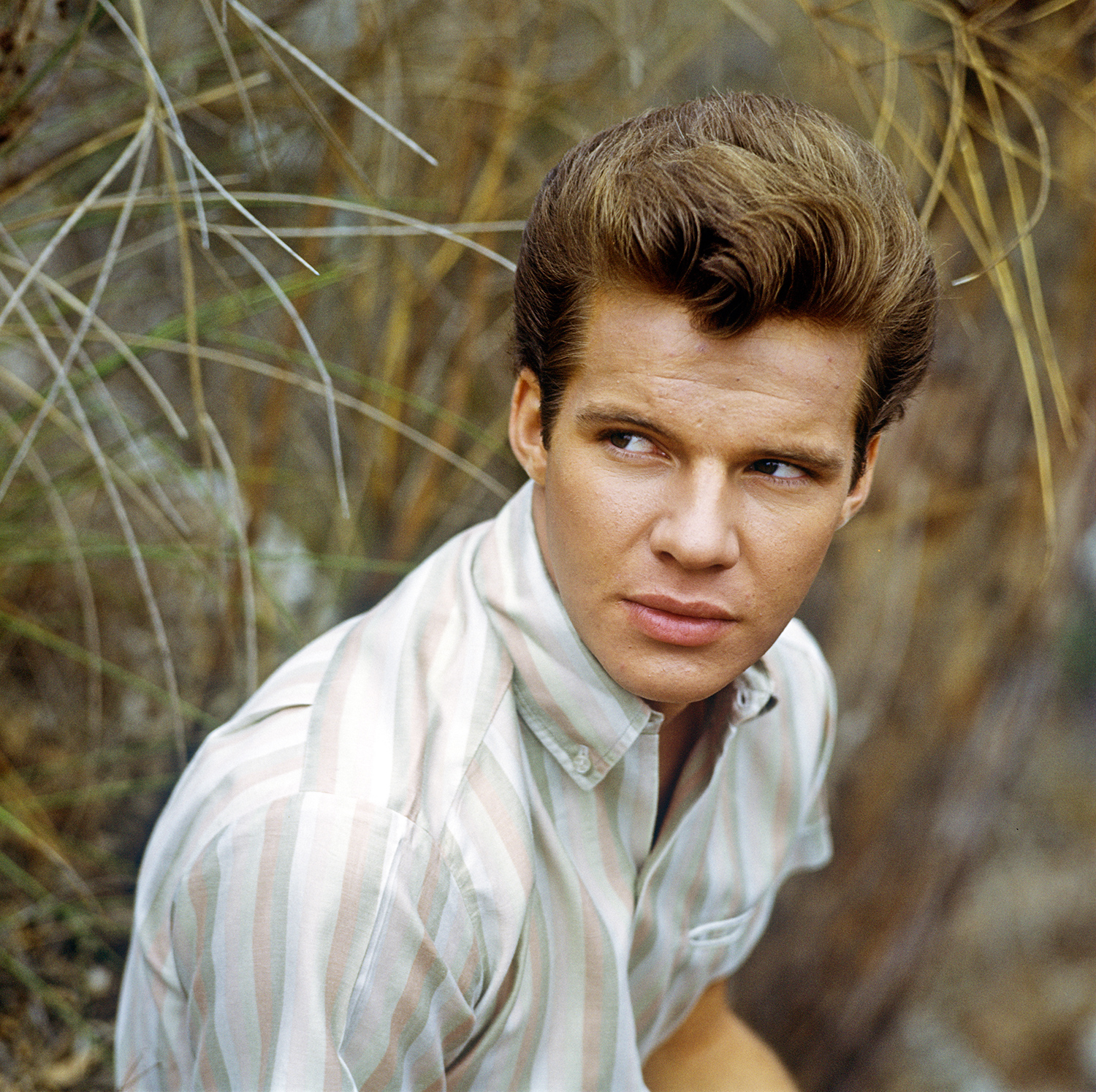

The world of 1961 was still reeling from the shockwave of rock and roll’s first wave, but the sonic landscape was quickly being smoothed, polished, and re-engineered for a new type of heartthrob: the clean-cut, utterly sincere teen idol. Standing tall in this era, a seemingly endless parade of ‘Bobbys’ and ‘Frankies,’ was the remarkable Bobby Vee. His career, beginning with the tragic happenstance of filling in for Buddy Holly, had rapidly blossomed, propelled by a genuine, earnest vocal delivery and a keen partnership with the Brill Building’s greatest minds.

Vee was signed to Liberty Records, and by 1961, he had already topped the charts with the iconic “Take Good Care of My Baby.” This success immediately set the stage for its successor. That follow-up, released later in the year, was the devastatingly polite surrender of “Run To Him.” It was a single, a self-contained three-minute drama that also later anchored his 1962 album, Take Good Care of My Baby. This piece of music arrived during Vee’s commercial peak—a period where his youthful vulnerability was perfectly matched with the sophisticated arrangements of producer Snuff Garrett and the songwriting alchemy of Gerry Goffin and Jack Keller.

The Velvet Gloom of the Studio

Imagine the recording studio as the tape rolls: a large, controlled acoustic space where the rough edges of early rock are being meticulously sanded down. Snuff Garrett’s production here is a masterclass in controlled melodrama, a hallmark of the era’s premium audio. The immediate impression of “Run To Him” is one of a sweeping, almost cinematic sadness. The song doesn’t explode; it swells.

The arrangement begins with a distinctive, insistent drum pattern, courtesy of a session ace like Earl Palmer, driving a tempo that is simultaneously urgent and constrained. It gives the song a forward momentum, a sense of propulsion towards the inevitable heartbreak. Layered above this rhythmic foundation, the piano plays a crucial role, not as a soloist, but as a rich textural pad, underpinning the harmony with wide, sustained chords. This provides the sonic bedrock for the rest of the mournful palette.

Then, the strings enter. Not just a token violin, but a full, rich orchestral sweep, moving in counterpoint to the vocal melody, providing the tears that Vee’s stoic delivery refuses to shed. The use of strings here is not gratuitous; it’s central to the song’s emotional architecture, elevating what could have been a simple pop lament into something approaching a pocket symphony. The shimmer of the high strings seems to suspend the moment of decision—the moment where the singer hands over his beloved.

The Voice of Resigned Romance

Vee’s vocal performance is the core of this tragedy. His voice, naturally high and clean, carries no trace of the aggressive swagger of earlier rock and roll singers. Instead, it’s infused with a heartbreaking sincerity. He sounds like the nice guy who loses, but accepts defeat with a weary nobility.

The lyrics, penned by Goffin and Keller, are a work of economical, yet profound, teenage angst. The singer has watched his girl’s affection drift, acknowledging that she has “found another guy who satisfies you more than I do.” The famous titular hook is not a plea, but an instruction, repeated like a mantra of surrender: “Run to him / Run to him.”

What makes the song’s climax so effective is the backing vocal arrangement. The Johnny Mann Singers provide a soaring, almost operatic choral echo on the title line. This group presence magnifies the singer’s loneliness, turning his personal agony into a grand, public announcement. It’s the contrast that works: a single, vulnerable voice against the overwhelming, unanimous chorus. The final, brief echo of the voices—a lingering, high-pitched “run to him”—leaves a chill that lasts well beyond the song’s quick fade-out.

The Subtlety of the Rhythm Section

While the strings and vocals dominate the sonic foreground, the rhythm section’s restraint is key to the song’s sophistication. The guitar work is minimal, confined largely to clean, arpeggiated figures or short, chiming chords that emphasize harmonic changes, never attempting a solo or a bluesy interjection. This choice prevents the song from slipping into simple rock and roll territory.

Listen closely to the dynamics. The bass line is steady, yet fluid, providing a melodic anchor that keeps the arrangement grounded. The overall texture is soft-focus, a warm wash of sound that wraps the listener in the narrative. This recording quality, free of harshness, makes it an excellent choice for a dedicated home audio setup, revealing the nuances of the orchestral overdubs and the subtle reverb on Vee’s voice.

“Run To Him” is not a song about fighting for love; it’s about recognizing the futility of the fight and offering a bittersweet, self-sacrificing blessing. It is the sound of the ultimate, polite, early-1960s gentleman. This kind of material perfectly cemented Vee’s identity as the sensitive boy-next-door, a dependable presence on the charts at the critical juncture just before the British Invasion changed everything.

“The song is a perfectly realized drama of dignified defeat, orchestrated with an intimacy that belies its chart ambition.”

An Enduring Echo

The themes of “Run To Him” transcend its era. The feeling of watching a love inevitably move on, and choosing to step aside rather than cause pain, is timeless. This is why the song still resonates in modern contexts—it taps into a universal well of graceful acceptance.

For a young person today, perhaps exploring this era for the first time, “Run To Him” provides a crucial historical lesson. It demonstrates that the early 60s, despite their reputation for bubblegum simplicity, produced emotionally complex popular music. The depth of the song’s feeling, despite the conventional structure, ensures its endurance. It’s a beautifully crafted piece of music—a moment when the factory line of pop hits produced a genuine, poignant artefact.

The song’s widespread success—it became a major transatlantic hit, reaching the Top 5 in the US and the Top 10 in the UK—was a validation of the Brill Building formula and Garrett’s production instincts. It showed that audiences, particularly the burgeoning teenage demographic, were ready for high-gloss heartbreak. The sophistication of the arrangement meant that even older, more critical listeners could appreciate the craft, even if the subject matter was purely adolescent. This track represents the high-water mark of the pre-Beatles teen idol, proving their staying power was built not on looks alone, but on truly great songs.

Listening Recommendations: Adjacent Moods and Arrangements

- Gene Pitney – “Town Without Pity” (1961): Shares the same dramatic, orchestrated sweep and sense of youthful emotional weight.

- Del Shannon – “Hats Off to Larry” (1961): Another early 60s hit about a dignified, if slightly bitter, romantic surrender.

- The Teddy Bears – “To Know Him Is to Love Him” (1958): Features a similar yearning, high-register vocal and a restrained, almost reverent mood.

- Dion – “The Wanderer” (1961): Provides a perfect contrast, showcasing the rougher, less orchestrated side of the contemporary male vocal hit.

- Ricky Nelson – “Travelin’ Man” (1961): An excellent example of another teen idol, with a slightly more laid-back, country-inflected approach to early pop hits.

- Johnny Mathis – “Misty” (1959): For those seeking the full, lush sound of the string-heavy pop ballad that underpinned this production style.