The vinyl crackle is the sound of the past reaching out, a tiny static comet streaking across a field of absolute stillness. Tonight, the needle drops on a record from a time just before the storm—before the British Invasion would sweep away a certain kind of meticulously crafted American pop music, a sound perfected by producers like Tommy “Snuff” Garrett and arrangers like Ernie Freeman. This is the world of Bobby Vee in late 1962, a place where heartbreak was polished to a sheen and every quiet moment felt like a close-up.

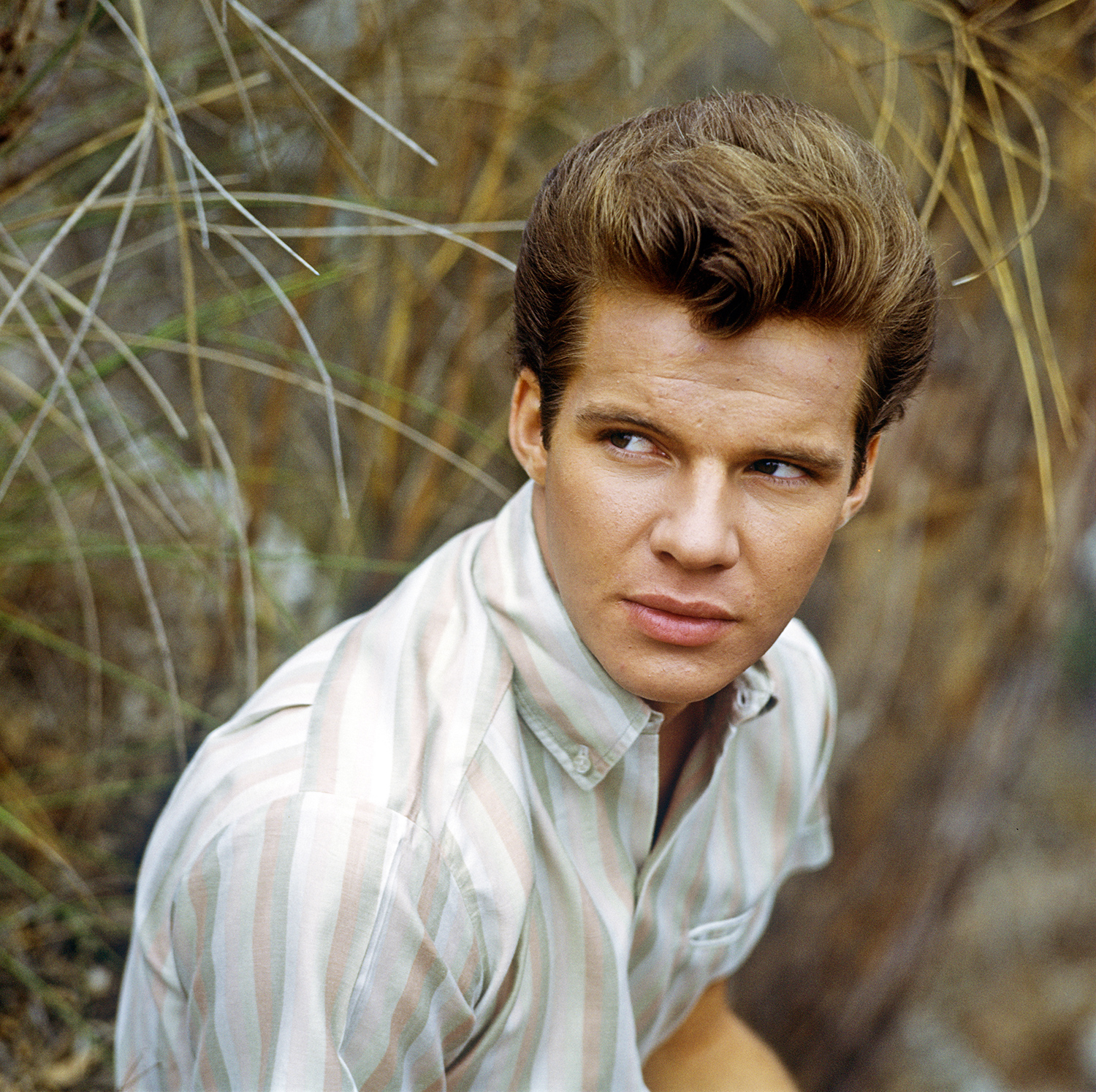

Vee, the former Fargo kid who—in a twist of fate that reads like rock and roll legend—stepped in to fill the shoes of the late Buddy Holly, had already established himself as a dominant force in the teen-idol firmament. He’d delivered chart-toppers like “Take Good Care of My Baby,” riding the wave of sophisticated, Brill Building-adjacent songwriting. His style was a pivot away from the raw urgency of earlier rock and roll, favoring a cleaner, more controlled vocal delivery that resonated deeply with the era’s maturing teenage demographic. By 1962, Vee was a Liberty Records flagship artist, a consistent hitmaker whose name guaranteed a certain level of craftsmanship.

“The Night Has A Thousand Eyes,” released as a single in late 1962, was no mere B-side filler; it was a carefully constructed statement. It was the title track that would later anchor his 1963 album of the same name. Produced by the aforementioned Snuff Garrett and arranged by the prolific Ernie Freeman, this piece of music represents the apex of the pre-Beatles, orchestrated pop sound, achieving a peak of number three on the Billboard Hot 100 and a similar ranking in the UK.

The Anatomy of a Suspicion

The song opens not with a guitar riff or a drum flourish, but with a tension you can feel—a rapid, stuttering pulse laid down by the rhythm section. It’s a clipped, nervous energy, immediately establishing the song’s central theme of anxiety and surveillance. The high-hat keeps a quick, tight tempo, yet the overall feel is restrained, never quite tipping into full dance-floor abandon. This push and pull between movement and dread is the key to the track’s longevity.

Ernie Freeman’s arrangement is a masterclass in adding color without crowding the core melody. His use of strings is particularly distinctive. They don’t simply swell sentimentally; they dart and shimmer, suggesting movement, like the titular eyes watching from the shadows. The strings are mixed high, providing an almost ethereal, cold sheen over the warmth of the bass and drums.

Vee’s vocal is the anchor in this shimmering landscape. He sings with a vulnerability that is the hallmark of the teen-idol era, but there is a genuine tremor in his voice—not over-dramatic, but subtly conveying the paranoia of a young lover convinced of betrayal. His performance carries the narrative: “The stars have a million eyes / The night has a thousand eyes / But all put together / Their light cannot compare / With the look in your eyes / When we kiss goodnight.” The lyric is brilliant, flipping the romantic cliché of celestial wonder into a terrifying metaphor for being judged, watched, and ultimately found wanting.

Shadows in the Studio

The instrumentation reveals a sophisticated studio approach. The bass line is prominent, walking with confidence even as the singer’s resolve wavers, grounding the track’s rapid tempo. The guitar, when it appears, is clean and trebly, providing brief, staccato fills—little bursts of brightness that quickly fade back into the gloom of the orchestration. A careful listen on a high-quality playback system, perhaps with a pair of finely tuned premium audio speakers, reveals the precision of the mix, where every element has its space.

This polished sound contrasts sharply with the raw garage recordings emerging elsewhere, yet it possesses its own form of grit. It’s the grit of a perfectly-pressed suit worn by a protagonist in a black-and-white film noir—an underlying tension beneath a flawless exterior. The piano largely serves a rhythmic and harmonic function, its chords blending with the bass to provide a strong foundation, occasionally offering a bright, chiming counterpoint to the darker strings. The subtle choir backing adds an almost religious layer of solemnity to the heartbreak, a common production trick of the time, elevating the teenage melodrama to something grander.

“The song is a perfect intersection of pop’s youthful sincerity and the complex, orchestral sophistication of Hollywood session musicians.”

The arrangement’s dynamics are particularly noteworthy. The song begins and ends with a relative softness, but the instrumental break halfway through offers a short, exhilarating lift, a momentary swell of orchestral drama that mirrors a flash of desperate realization before Vee returns to the verse, his voice hushed but resolute. This structure avoids the trap of many contemporary pop songs, which often relied solely on repetitive verse-chorus forms.

The Long Echo of Betrayal

The story told by “The Night Has A Thousand Eyes” is simple, yet universal: the dread that your partner’s love is a facade. It is a mood perfectly suited to the early 1960s, an age of surface perfection in fashion and media that often masked deeper currents of insecurity. This is why the song still resonates today. It is the soundtrack to that quiet, cold moment in the early hours when you turn over in bed and realize something is fundamentally wrong.

It is a subtle masterpiece of arrangement and performance, one that paved the way for the lush sound of future rock records while existing squarely within the vanishing world of the pre-Beatles American pop machine. Vee’s ability to take this composition—written by the team of Benjamin Weisman, Dorothy Wayne, and Marilyn Garrett—and inject it with such believable, contained despair secures its place as more than just a pop hit. It is a genuinely affecting narrative delivered in under three minutes. For those who dismiss the teen idol era as merely saccharine, this track demands a serious re-evaluation. It’s mature music wearing a youthful disguise.

The song’s texture and pacing also provide a remarkable lesson for aspiring musicians. For those currently undertaking guitar lessons and struggling to understand how a simple chord progression can carry a complex emotion, “The Night Has A Thousand Eyes” offers clarity. Its structure is deceptively simple, but the emotional lift comes entirely from the nuanced arrangement—the interplay between the light, almost jazzy rhythm and the heavy, melancholic strings. It teaches restraint, a quality too often forgotten in today’s maximalist productions. The song doesn’t shout its pain; it whispers it, ensuring the listener has to lean in closer to hear the secret. This intimacy is what makes the experience of re-listening so compelling.

The track’s legacy is a quiet one, overshadowed perhaps by Vee’s own bigger hits or the massive cultural shift that followed shortly after its release. Yet, it endures in a way that is distinctly timeless, a perfect capsule of teenage angst filtered through the genius of the L.A. session world. It invites us to consider the artistry required to craft such immaculate popular music, and to mourn the loss of a brief, brilliant moment in musical history.

Listening Recommendations (Adjacent Mood/Era/Arrangement)

- “Go Away Little Girl” – Steve Lawrence (1962): Shares the same ‘sophisticated plea’ mood and features the dramatic, orchestral sound of the era.

- “It’s My Party” – Lesley Gore (1963): Another example of orchestral teen melodrama, but delivered with a slightly more overt, operatic sense of tragedy.

- “Only Love Can Break a Heart” – Gene Pitney (1962): Similar lush arrangement and a high-tenor vocal that perfectly conveys vulnerability and despair.

- “Tower of Strength” – Gene McDaniels (1961): Excellent example of Snuff Garrett/Ernie Freeman’s signature studio collaboration and wall-of-sound orchestration.

- “Where Did Our Love Go” – The Supremes (1964): Though slightly later, it maintains a similar blend of light, propulsive rhythm with underlying vocal heartbreak.

- “Crying” – Roy Orbison (1961): The gold standard of dramatic pop balladry, sharing a similar sense of high-stakes, cinematic sorrow.