I remember the first time this particular piece of music truly hit me. It wasn’t on a crackling transistor radio, or a dust-covered 45. It was late at night, a rainy drive, and the needle dropped on a crisp vinyl compilation. In an instant, the world of the car dissolved, replaced by a cinematic slice of 1962: the moment right before the British Invasion fully washed over American pop. Bobby Vee’s voice, clean and aching, cut through the quiet rain. The song was “Sharing You.”

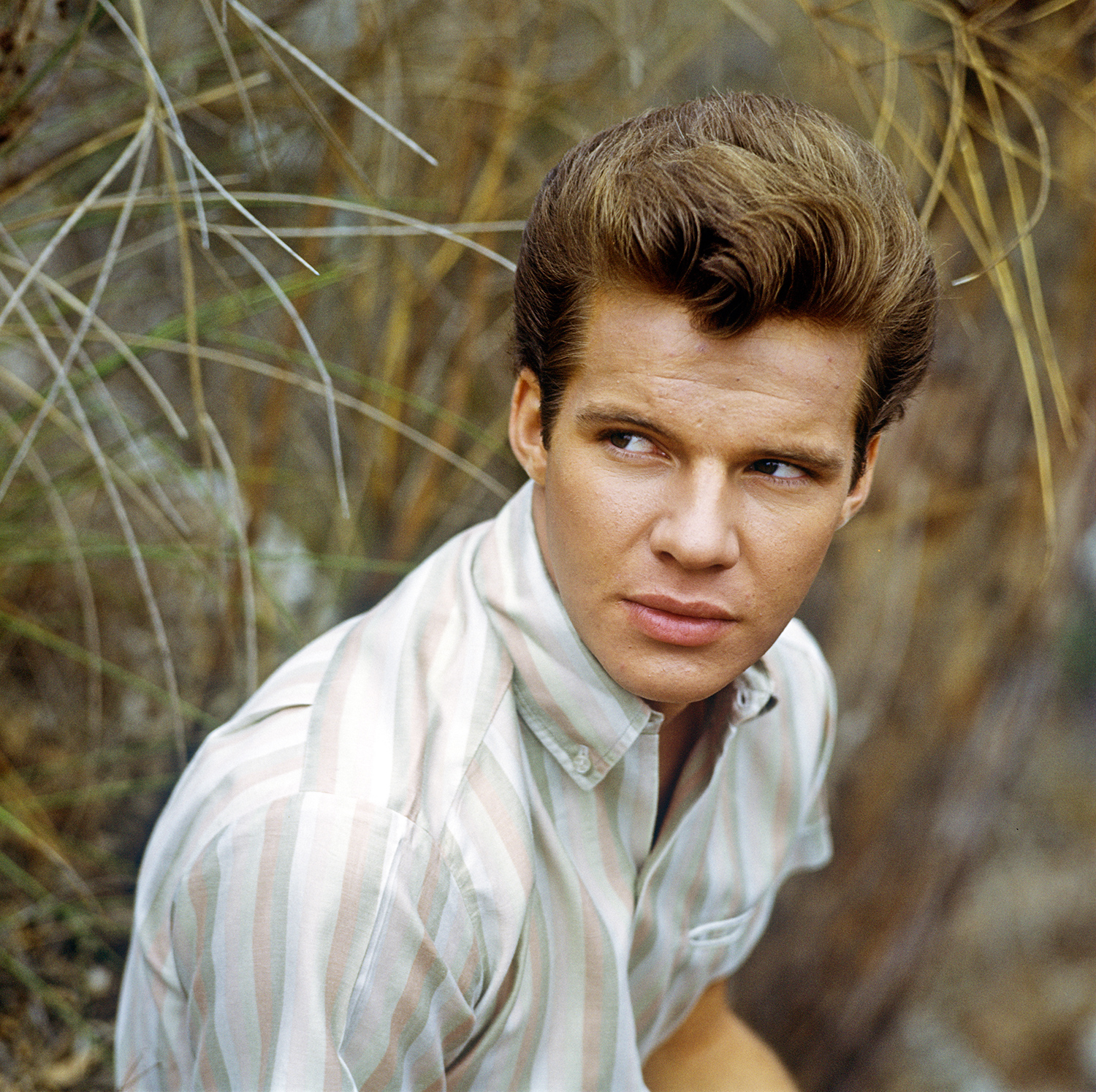

It is easy, perhaps too easy, to file Bobby Vee away in the neat, retro category of “teen idol.” He was the handsome Minnesota kid who stepped into a legend’s shoes and built a formidable career on the back of melodic, meticulously crafted pop songs. But to focus solely on the persona is to miss the substance, particularly the depth of his early-sixties material. “Sharing You,” penned by the iconic Brill Building duo of Gerry Goffin and Carole King, is one such gem—a two-minute, highly efficient journey into sophisticated melancholy.

The date in the blog title, 1965, is an interesting inflection point, because while the song was charting and being promoted in those mid-decade years through performance, its moment of creation and primary chart run was definitively 1962. It was released on Liberty Records, a crucial label for Vee, and was a key track on his 1962 album, A Bobby Vee Recording Session. This period marked the apex of his pre-Beatles reign, following massive hits like “Take Good Care of My Baby” and “Run to Him.”

He was still working closely with producer Snuff Garrett, the man responsible for Vee’s signature, polished sound. Garrett was a master of the pop record production aesthetic of the time, often employing lush orchestration to give a slightly adult sheen to the teenage drama. This track is a perfect example of that refined approach. The 1965 lens, in truth, is a retrospective one—it’s the moment the old guard, the pre-Beatles kings like Vee, were being reassessed in the wake of the new seismic shift.

Studio Sound: Restraint and Resonance

The song opens not with a guitar riff, but with a rhythmic, almost hesitant thrumming that anchors the entire piece. The drumming is minimal, precise, functioning as a metronome for the anxiety in the lyric. A prominent piano line handles the main harmonic movement, its chords struck cleanly and with a soft decay that gives the track its sense of space. It sounds less like a typical rock and roll track and more like a carefully constructed Broadway ballad, truncated for the Top 40.

The instrumentation is where the true brilliance of Garrett’s production shines. Beyond the core rhythm section, we are met immediately with the unmistakable presence of The Johnny Mann Singers, whose backing vocals are not mere harmonies but a Greek chorus for Vee’s sorrow. Their collective, wordless “oohs” and “aahs” fill the stereo field, lifting the dynamic range and giving the arrangement an emotional weight that Vee’s own youthful tenor, though sincere, might not achieve alone.

Vee’s vocal performance is a marvel of restraint. He doesn’t belt; he confides. He articulates the painful geometry of a love triangle—the emotional cost of “Sharing You”—with a light, yet firm touch. The microphone seems slightly distant, capturing a sense of air around his voice, lending the whole sound a slightly glamorous, distant quality. For a listener committed to premium audio reproduction, this particular recording offers a masterclass in late-era pre-wall-of-sound clarity, allowing each instrument its own discrete space.

The absence of a fiery guitar solo, or any real grit, is intentional. It keeps the song squarely in the realm of high-school heartbreak told through a sophisticated, adult filter. If there is a lead instrument in the breaks, it’s the gentle swell of a string section—violins performing short, ascending phrases that act like a momentary sigh of shared sadness. This contrast—the simplicity of the lyric versus the orchestral sweep—is the song’s primary dramatic device.

“It is the sound of a private wound dressed in a velvet tuxedo.”

The Cultural Context: Looking Back from 1965

By 1965, the year of the user-prompt, Vee’s hit-making momentum had slowed considerably, a casualty of the British Invasion’s shockwave. His label, Liberty, had been pushing new, often more frantic sounds, but “Sharing You” stood as a pristine artifact from a gentler time, a reminder of the teen-pop monarchy that had just been overthrown. This song, like many of his early Goffin-King collaborations, showed a subtle sophistication that differentiated him from many of his contemporaries. It demonstrated a willingness to tackle subjects with emotional nuance, a credit both to the songwriters and to Vee’s developing maturity as a vocalist.

Think of it: two minutes and three seconds to unpack the complexity of a relationship where one partner must be perpetually divided. This is the glamour of 1962, the tailored suit and the perfectly coiffed hair, but the subject matter is pure, unadulterated grit. It is a testament to the structure of the album A Bobby Vee Recording Session that it contained such high-quality, memorable songs alongside his better-known singles. The song’s short runtime only intensifies its dramatic core.

I recently worked with a young musician who was taking guitar lessons and struggling to understand how to apply simple, clean arrangements to emotional songs. I pointed them directly to this track. Listen to the way the bass line walks, keeping time with the drums—it’s never showy, always supportive. The rhythmic bed is entirely functional, allowing the drama to play out in the foreground. This minimalist approach is what makes the song so lasting.

Micro-Vignettes: The Song’s Endless Replay

Vignette 1: The Diner Booth

Two friends sit in a late-night diner, the fluorescents buzzing. One, a boy, recounts a recent, difficult breakup. The other, the girl, doesn’t offer advice, just listens, stirring her lukewarm coffee. In the background, from a jukebox played too loud, comes the line: “I can’t feel the thrill you give me / Knowing she’s got half of you.” It’s the perfect sonic mirror for the shared, quiet desperation of their conversation. The song, though decades old, articulates the timeless arithmetic of a love that simply doesn’t add up.

Vignette 2: The Old Tapes

An older couple is clearing out their attic. They find a box of old reel-to-reel tapes. Dusting one off, they put it on a revived player. Out pours the clear, youthful sound of “Sharing You.” They smile. The husband remembers trying to learn the piano intro to impress his wife when they were dating. She laughs, recalling the night he drove her home and the song was playing on the radio, its melancholy somehow making the moment feel more important, more tragically romantic than it actually was. The song is a key to unlock a past, a short narrative that lasts only as long as the record spins.

Vignette 3: Streaming Culture

A contemporary college student, deep in a playlist of “Sad Songs of the Sixties,” clicks shuffle. The compressed audio of the modern format still cannot mute the feeling. They recognize the song instantly from its use in a vintage film clip they saw. They don’t know Bobby Vee, but they instantly recognize the feeling of being the half-loved party, a universal story told beautifully and economically. This piece of music transcends its era, finding new resonance in a world of infinite music streaming subscription choices.

Conclusion: A Quiet Masterpiece

“Sharing You” is a masterwork of conciseness. At just over two minutes, it captures the entirety of a sad, resigned emotional state without ever overstating the case. It is a brilliant Goffin-King composition, brought to life by Snuff Garrett’s disciplined production and Bobby Vee’s effortlessly sincere vocal delivery. It serves as a reminder that before the guitars got loud, before the music fractured into a thousand sub-genres, there was a brief, luminous period where pop music embraced sadness with such sophisticated simplicity. Seek it out, put on your best headphones, and let the quiet anguish of a shared love wash over you.

Listening Recommendations

- “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” – The Shirelles: Another brilliant, early Goffin/King composition exploring romantic anxiety with vocal group polish.

- “It Might As Well Rain Until September” – Carole King: The songwriter’s own version, showcasing the lyrical theme of resignation with an equally melancholic feel.

- “Roses Are Red (My Love)” – Bobby Vinton: Shares the clean, easy-listening pop arrangement and slightly melancholic tone popular on the charts at the time.

- “Crying” – Roy Orbison: Features similar dramatic orchestral flourishes supporting a vocal performance of intense, controlled sorrow.

- “Gonna Get Along Without You Now” – Skeeter Davis: A mid-tempo track that captures a similar emotional ambiguity of moving on from a difficult relationship.

- “Go Away Little Girl” – Gerry Goffin (demo): Listening to the songwriter’s intimate take reveals the core ballad structure beneath the pop production.