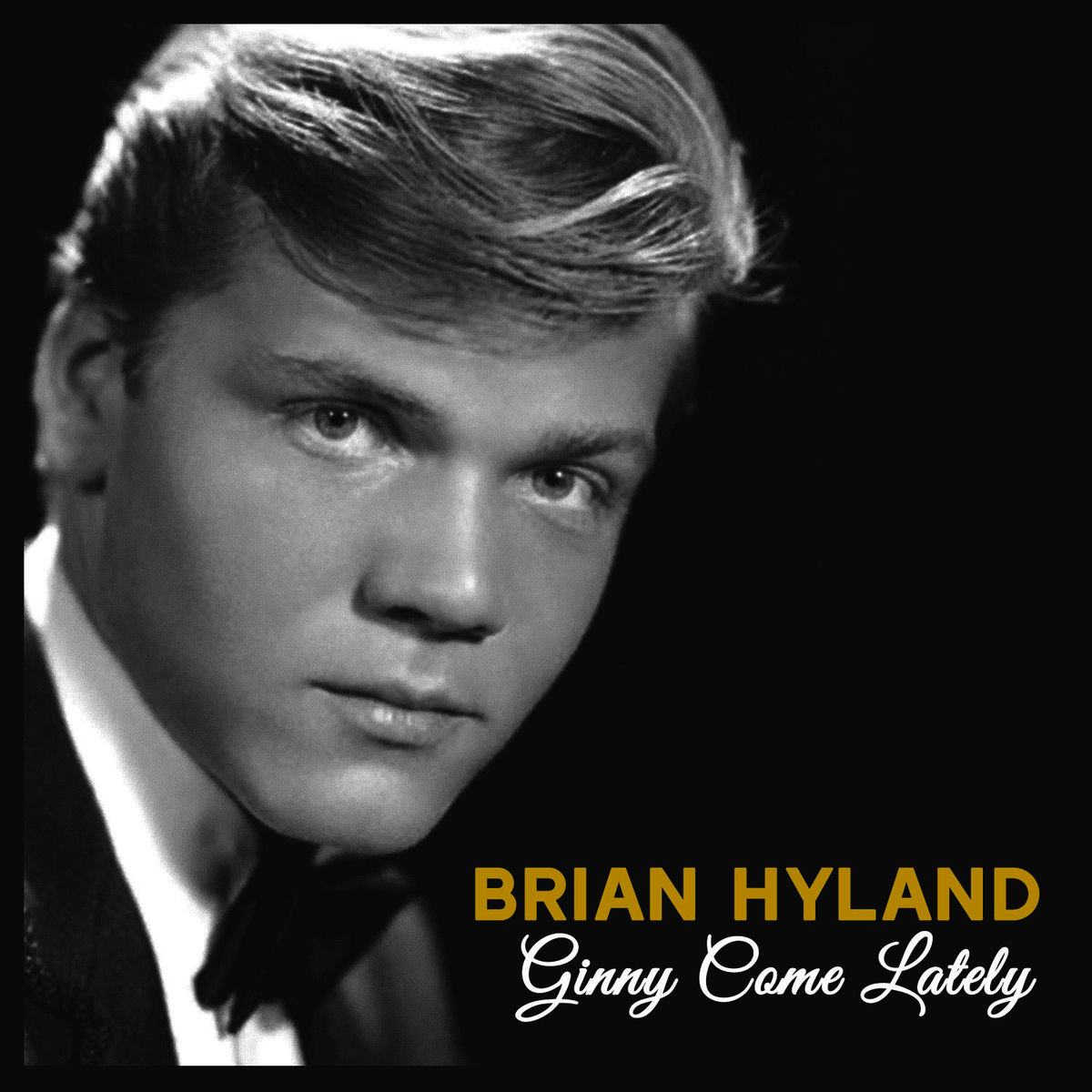

The scent of stale coffee and the distant, metallic clang of a service door. That’s where the memory begins, not in a sun-drenched sock hop, but in the velvet gloom of a late-night radio dial. The glow from the jukebox is weak, casting long shadows across the counter. The world outside is 1962, suspended precariously between the clean-cut optimism of the Eisenhower years and the seismic cultural shift looming on the horizon. And then, the voice—clean, slightly tremulous, utterly sincere—of Brian Hyland.

I first encountered “Ginny Come Lately” not as a vintage track, but as a kind of sonic ghost, a perfect evocation of a mood I didn’t know I was searching for. It was a song that articulated the quiet tragedy of a slow-motion breakup, a romance that simply fades instead of exploding. It is a brilliant, deceptively simple piece of music, released in February 1962 on the ABC-Paramount label. Hyland, still riding the wave of his earlier novelty smash, was already pivoting hard into the smooth, melodic territory of the teen idol, positioning himself as the sensitive counterpoint to the rawer edge of rockabilly.

The Architecture of Wistful Pop

This pivot was masterminded by the songwriting and production tandem of Gary Geld and Peter Udell, who penned this tune and many of Hyland’s subsequent hits, most famously the even larger success, “Sealed with a Kiss,” which followed just a few months later. Their method was a cornerstone of the burgeoning Brill Building sound: craft melodies of unimpeachable sweetness, then dress them in arrangements of surprising sophistication. The 1962 single, which later found a home on the quick-turnaround album Sealed with a Kiss that same year, stands as a testament to their knack for packaging pathos.

The opening is cinematic in its simplicity. We begin with a quiet, rolling figure on the piano, a gentle pulse that is immediately joined by the low, rich register of an acoustic guitar. This initial restraint sets the melancholy tone. It avoids the typical swagger of early 60s pop; instead, it invites the listener into an intimate confession. This sound is what separates the enduring hits from the footnotes—the ability to create a world in the first four bars.

Hyland’s vocal performance is key. His phrasing leans forward, earnest and slightly breathless, but never overwrought. He embodies the young man caught in the emotional currents he can barely name. The dynamics of the arrangement mirror his internal conflict: a subtle, almost imperceptible swell of strings enters beneath the second verse, a wash of sweet sorrow that never threatens to overwhelm the narrative. It supports, it elevates, it aches.

The rhythm section, unobtrusive but essential, provides a steady, measured beat that walks the line between a heartbroken shuffle and the inevitable forward movement of time. The bass line is warm, anchoring the more ethereal qualities of the orchestration. The percussion uses brushes and light snare hits, emphasizing texture over thunder. It sounds less like a bombastic stage performance and more like a carefully mic’d conversation meant for listening on a quality home audio system, where every shimmer of the cymbal and every nuance of the vocal reverb can be appreciated.

“It is a song that articulates the quiet tragedy of a slow-motion breakup, a romance that simply fades instead of exploding.”

The Geography of ‘Lately’

The lyrics, penned by Udell, are remarkably mature for the teen-pop market. “Ginny Come Lately” isn’t about being dumped for a rival; it’s about the slow, agonizing realization that Ginny’s heart is simply gone. She is physically present but emotionally distant—the worst kind of ghosting. Hyland sings: “You used to call me darling, and you meant it then / We used to kiss each other, and you’d kiss me back again / But lately, baby, you’re not the same / You say you love me, but your eyes call out my name.”

That specific detail—”your eyes call out my name”—is devastating. It’s the kind of concrete, observational lyricism that elevates the track beyond formulaic teen romance. It’s a moment of deep, personal insight, a narrator realizing that the true language of love is not words, but presence and intent, and Ginny is failing on both counts.

The bridge offers the song’s grand emotional climax, the only moment where the arrangement truly allows itself to sweep. The strings rise in a gorgeous, yearning arc, and a muted electric guitar delivers a brief, melodic counterpoint. It is a moment of controlled catharsis before the piece of music settles back into its resigned, mid-tempo pace for the final verse. This judicious use of instrumentation shows the mastery of the arrangement, reportedly handled by Stan Applebaum on many of the Geld/Udell collaborations. This song didn’t need to shout its sorrow; it preferred to whisper its regrets with an orchestral sigh.

The song was a substantial transatlantic hit, peaking at number five in the UK and a respectable number 21 on the US Billboard Hot 100. Its success, however, was quickly overshadowed by its immediate follow-up. This one-two punch of “Ginny Come Lately” and “Sealed with a Kiss” cemented Hyland’s identity: no longer just the boy in the bikini, but the voice of sensitive, vulnerable adolescence—a sound soon to be utterly washed away by the tide of the British Invasion.

The appeal remains simple, yet profound. Today, when listeners purchase music streaming subscription access, they are often seeking an emotional connection that transcends a simple download. They seek the resonance of a moment, and “Ginny Come Lately” provides it. It’s not just an oldie; it’s a beautifully preserved diorama of a particular flavor of early 60s heartache, proof that heartbreak, like a perfectly preserved suit from an earlier era, retains its elegant shape, even across the decades.

Listening Recommendations

- “Sealed with a Kiss” – Brian Hyland (1962): The immediate, slightly more popular follow-up single; shares the same production polish and wistful, yearning theme.

- “Only Sixteen” – Sam Cooke (1959): Features a similar narrative focus on young love and regret, delivered with a comparable smooth vocal style and gentle orchestration.

- “Travelin’ Man” – Ricky Nelson (1961): Another early 60s single with sophisticated production and a clean, light tenor, though with a more adventurous, pop-country arrangement.

- “Gonna Find Her” – Gary Troxel (1963): A lesser-known but thematically adjacent song that utilizes that slow, building orchestral sweep common to mid-tempo early 60s ballads.

- “Since I Don’t Have You” – The Skyliners (1959): Features the lush, operatic orchestral backing and dramatic vocal delivery that influenced the arrangement style of Hyland’s early ballads.