I was driving late one autumn night, radio dial scrolling through the static and ghost-signals of distant towns, when it hit—a sound so familiar it felt hardwired into the American consciousness. It wasn’t a cover, stripped bare for coffee-shop melancholy, nor the sanitized nostalgia of a recent remix. It was the original 1962 recording of Bruce Channel’s “Hey! Baby,” and suddenly the car felt less like a modern machine and more like a time capsule, vibrating to a rhythm that predated the very concept of music streaming subscription services.

It’s a deceptively simple piece of music, this single from a young Texas songwriter. The moment the track begins, it transports you not just to a specific year, but to a specific texture: the clean, close mic placement in Clifford Herring Studios in Fort Worth, Texas, where the song was tracked. You can almost feel the air in the room, tight and dry, giving the percussion an immediate, thwacking presence. It was co-produced by Channel himself and Major Bill Smith, who first issued it on his local LeCam label before Smash Records, a Mercury subsidiary, picked it up for national distribution.

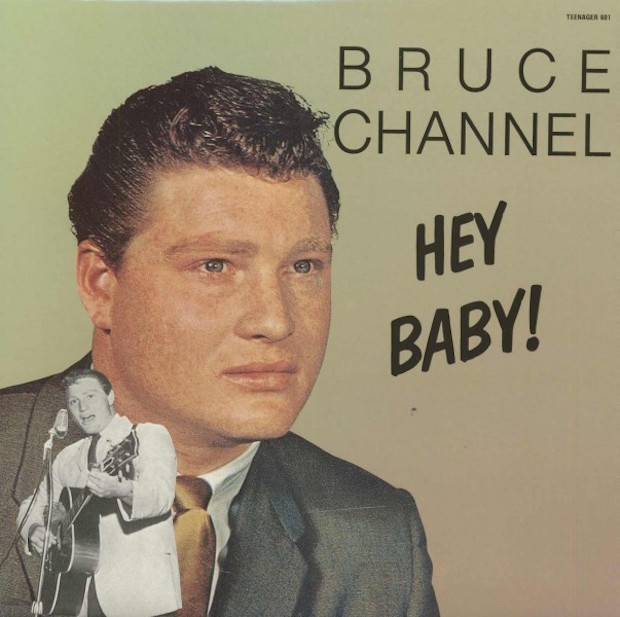

This journey from a local Texas label to the top of the Billboard Hot 100 is the classic American music dream, and for Bruce Channel, “Hey! Baby” was his golden ticket. It wasn’t just a hit; it was the hit, a towering monument in a career otherwise characterized by the steady work of a professional songwriter. The song stands alone, its success so stratospheric—a three-week run at number one in the U.S. and a major splash in the UK—that it defined his entire public persona. The album it belonged to, also titled Hey! Baby, became an artifact of this single moment, more a showcase for the star track than a cohesive artistic statement.

The Anatomy of an Earworm

The genius of “Hey! Baby” lies in its relentless, infectious rhythm and its economy of instrumentation. This is not the baroque pop of later eras, nor the raw, untamed garage rock that was just around the corner. It is a perfect bridge between the tight arrangements of early rock and roll and the burgeoning, shuffle-heavy beat of the British Invasion, which, ironically, it helped to inspire.

The rhythm section is the song’s heartbeat: a foundational kick-snare pattern, a lightly thumping bassline from Jim Rogers, and a steady, almost nervous energy that propels the whole thing forward. Ray Torres’s drumming, reportedly a major feature, locks down a slightly off-kilter, driving shuffle, pushing the energy just slightly ahead of the beat, giving the track its irresistible swing. The electric guitar work, attributed to players like Bob Jones and Billy Sanders, is spare but effective. It provides a crisp, echoing accent—a short, stabbing chord or a quick, clean single-note run—that fills the space without ever cluttering the mix. There is no major piano work on the core track; the harmonic support is provided subtly, allowing the lead voice and the signature riff to shine.

And then, there is the voice of the instrument that made it indelible: the harmonica.

The intro is a masterclass in hook writing. That sustained, wavering first note, delivered by a young Delbert McClinton, who had been performing with Channel, is a clarion call. It doesn’t scream; it yearns. That specific vibrato, followed by the tight, blues-infused melodic riff, is instantly recognizable. It is a deceptively simple, four-bar figure, yet it’s the key to the entire dynamic. It enters, asserts its swagger, and then pulls back, giving Channel’s vocal its space.

Channel’s performance is earnest, direct, and just rough enough around the edges to feel real. He’s singing a universal plea, delivered with a mix of hopeful anxiety: “Hey, hey baby, I wanna know if you’ll be my girl.” His vocal has a slight echo, adding depth and a kind of cavernous intimacy, as if he’s singing to you from across a crowded, noisy dance hall. This contrast between the smooth, soulful vocal delivery and the gritty, breathy texture of McClinton’s harmonica is the secret sauce.

“The simple, sustained yearning of a blues harmonica was the unlikely spark that lit the global fire of 1962 pop.”

The Unlikely Architects of a Movement

The history books love the vignette that connects “Hey! Baby” directly to the biggest band in the world. While touring the UK in 1962, Channel and McClinton played a show that was supported by a still-developing, Liverpool-based quartet: The Beatles. The story goes that John Lennon, who was reportedly fascinated by the track and owned it on his jukebox, spoke with McClinton and picked up tips on harmonica technique.

You can hear the effect immediately. The harmonica work on The Beatles’ first single, “Love Me Do,” released later that year, bears a distinct family resemblance to the sound McClinton crafted for “Hey! Baby.” It is a direct line of influence: a Fort Worth session man, a moment of cultural exchange in a provincial British town, and the subsequent reshaping of popular music. It’s a remarkable cultural transaction, proving that often, the largest waves are caused by the smallest stones dropped into the water.

This is why, over sixty years later, this single resonates far beyond the typical scope of a “one-hit wonder.” It’s a perfect sonic snapshot of a moment when R&B and country influences were distilled into pure, unpretentious pop gold. The arrangement balances restraint and catharsis expertly. The energy is high, but it never spills over into chaos. It holds its tension, which is why it continues to work in modern settings, from film soundtracks to stadium anthems.

For the serious listener investing in high-end home audio equipment, this record is a surprisingly rich experience. The separation between the instruments is clean, and the percussive elements—especially the sharp attack of the snare and the metallic sizzle of the cymbals—come through with satisfying clarity, allowing the nuances of the performance to emerge.

In the end, “Hey! Baby” is more than just a dance number; it’s a foundational text. It’s the sound of American optimism and yearning, packaged into two minutes and twenty-seven seconds of pure pop euphoria, ready to be discovered and re-discovered by every generation of listener who just wants to know: Will you be my girl? The question is timeless, and the hook, apparently, is immortal.

Listening Recommendations

- “Let’s Twist Again” – Chubby Checker (1961): Shares the same energetic, party-starting rhythm and early rock and roll enthusiasm.

- “Runaround Sue” – Dion (1961): Similar narrative simplicity and driving rhythm section, focused on a charismatic male vocal.

- “Love Me Do” – The Beatles (1962): A must-hear for the direct influence of Delbert McClinton’s harmonica style on John Lennon.

- “I’m Walkin'” – Fats Domino (1957): Provides the foundational New Orleans R&B swagger and easy-going vocal charm that Channel built upon.

- “Peggy Sue” – Buddy Holly (1957): Another prime example of the tight, clean, early rock and roll sound, with a memorable, driving percussion effect.