I like to begin with tape hiss. Before the music has a face, there’s that faint air in the room—the sound of possibility settling into place. On “True Love Ways,” you can almost picture the New York hall: lights low, players poised, a cough in the distance, a chair leg nudged back into stillness. Then comes a hush that isn’t silence at all but expectation, a held breath before a vow. And when Buddy Holly begins to sing, the voice is not the jangling comet of “Peggy Sue” or the kerosene spark of “Rave On.” It is close, conversational, poured just above a whisper, as if he has stepped a little nearer to the microphone because this confession should be said, not shouted.

This was late 1958, the Pythian Temple in New York City, a large space known for that stately, almost cinematic bloom around a voice. The session was led by arranger and conductor Dick Jacobs, a Coral Records project designed to bring Buddy’s songs into an orchestral frame. The date matters: October 21, 1958—just months before Buddy’s death—and you can hear the hinge of a career in the way the track opens its arms to strings, reeds, and room tone. It’s not just expansion; it’s intent. There’s a sense of an artist wide awake to the grown-up palette at his disposal.

“True Love Ways” would not appear in the market until after the tragedy, first surfacing on The Buddy Holly Story, Vol. 2. It’s a curious irony that a recording so alive to the future entered the world as part of a posthumous narrative, gathering listeners who were already deep in mourning. Released as a single in Britain in 1960, it made a respectable showing, climbing into the UK Top 30, while in the United States it passed without chart impact. But charts feel beside the point with a performance this intimate; numbers can’t tabulate the way a voice occupies your chest. Still, the paper trail is the paper trail, and it places the song firmly in that 1960 window, with Coral handling the label duties.

The composition itself bears the clarity of a promise said slowly. Buddy Holly and Norman Petty share the writing credit, and biographers have often connected the song to Buddy’s marriage, with his widow recalling that it was written as a kind of gift. Whether you approach it as a wedding-night whisper or simply as a statement of devotion, the architecture is gentle and deliberate: short phrases, patient cadences, a melody that leans forward and then rests, like a hand closing over another on a table. The words are plain—no acrobatics, no baroque turns—and that plainness is the point. “True Love Ways” isn’t trying to dazzle; it’s trying to abide.

What makes the recording shimmer is its arrangement, which moves like light through gauze. Violins rise in soft lattices; a tenor saxophone shades the edges; the drums tick with a brushed reserve. Near the start you can hear a small cue from the keyboard and a rustle of bodies getting settled—poignant studio evidence of people making a promise real. The room leaves a halo around the vocal, just enough reverberation to suggest closeness rather than echo. This is the art of “don’t overfill the glass.” Every swell knows when to recede.

Listen for how the strings cradle the top line without swallowing it. They come in as if unspooling a curtain behind Buddy, then part, then gather again for the final pledge. You can hear the arranger’s intelligence in those dynamics—how one soft phrase invites another, how the orchestration compliments the whisper rather than trying to upstage it. The attack of the ensemble is gentle, but the sustain translates as conviction.

The players list has become part of the lore: jazz and pop stalwarts brought in for color and expertise. One of those hands belonged to Al Caiola on guitar, who slips into the fabric like a cool shadow, keeping the texture grounded even as the strings float. It’s the sort of session detail you might miss on a casual listen but feel all the same; the rhythm track doesn’t argue, it reassures.

At the center of it is Buddy’s timbre—warm breath on the mic, consonants feathered rather than clipped, vowels that lengthen in the last balladry of the 1950s. There’s very little vibrato; instead, he sings in straight tones that bloom at the end of a line, which makes the moments he leans into a word feel like a hand squeeze. If you’ve ever sat across from someone you love and heard them choose careful words, you know this tone. It’s not only a performance; it’s a manner.

The piano enters softly, giving the pitch that steadies the first line and occasionally gilding a cadence with a simple upper-voice figure. It does not decorate for decoration’s sake. It affirms. If you’re listening on good speakers, pay attention to how those few notes open the trellis for the voice to climb—they act like a discreet nod from the bandstand saying, “We’re with you; say it.”

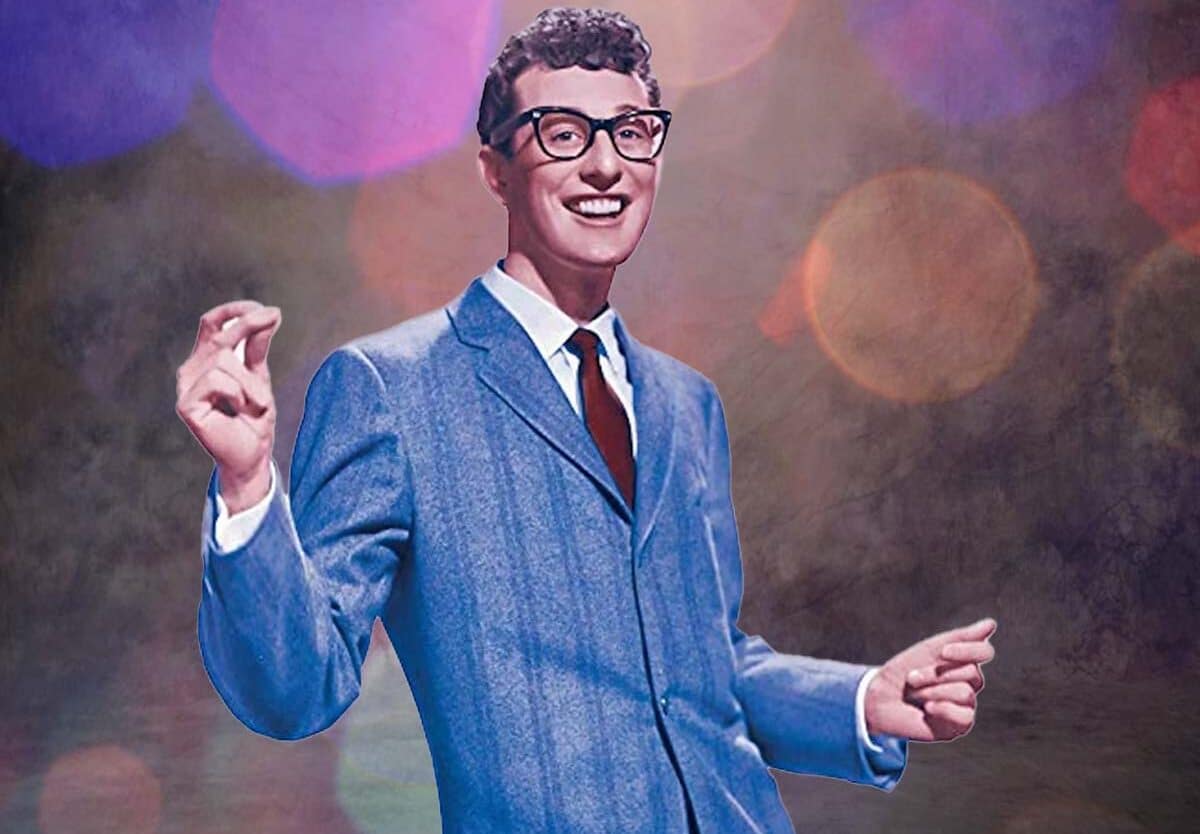

“True Love Ways” also provides a counter-story to the Buddy Holly many people hold in their heads. We mind-picture the glasses, the Cricket beat, the fast, clean downstrokes; we hear the strike of a Stratocaster and the propulsion of young rock and roll. Here, the tempo relaxes into a slow heartbeat, and the entire canvas tells us that patience is an expressive device. The glamour is present—strings can’t help but add velvet—but so is the grit of a live take: breaths, slight sibilants, and that human hush that no algorithm can fabricate.

Because this is a piece of music that lives in vows rather than fireworks, it travels unusually well across decades. In 1965, Peter and Gordon turned it into a transatlantic pop statement, reaching high in both the UK and US and proving that the tune’s simple architecture could hold different vocals, different ages, different arrangements. Fifteen years later, Mickey Gilley’s country reading topped the country charts, a reminder that some promises wear cowboy boots just fine. Different rooms, different accents, same hinge at the heart.

There’s the historical arc, and then there’s the private arc of how we meet the song. Three small stories:

A kitchen at 1 a.m., light over the sink, two people finishing dishes they should have done hours ago. The radio is low because the child is asleep at the end of the hall. Someone hums the melody without realizing it. A hand touches a shoulder; nobody speaks.

A bus winding out of a city, winter coating the windows. In the seat across the aisle, an older man reads a letter twice. The younger woman beside him looks out into the dark and traces one finger on the glass in time with the strings. The city recedes and the saxophone steps forward like a final streetlight.

A thrift store in a town you’re only passing through. In the rack of brittle LPs, a familiar portrait, and you remember the first partner you ever slow-danced with, the clumsy sway of it, the anvil of your own heart. You buy the record for a dollar even though you have no turntable. That kind of keepsake doesn’t need a needle.

As a recording, “True Love Ways” benefits from close listening. This is where, if you put on studio headphones, the specifics come alive—the chest resonance, the tiny swell when the strings breathe, the way the drum kit is felt more than heard. You can index the distance between voice and microphone by how the sibilants bloom in the air; you can hear the room, and in hearing it, you see it, a kind of x-ray of the past on the surface of the present.

There’s craft to admire, too, in the lyric’s discipline. The lines are short, declarative, and paced to the breath. The prosody fits the melody as naturally as speech—no ungainly crams, no syllables forced into odd corners. The effect is conversational reverence. When the strings rise behind a promise, it feels earned because the line earned it.

Ernie Hayes’s keyboard cues, so briefly audible in some versions, provide a functional poetry: they say “here’s home,” not by invoking theory, but by nudging the vocals onto a secure ledge. It isn’t just accompaniment; it’s hospitality. And when a saxophone answers a phrase, it does so with a tone that is candlelit rather than club-loud, a reminder that horns can murmur, too.

For collectors and musicians, this track also invites a kind of reverse-engineering. The harmonic movement is comfortable, anchored in well-worn progressions that countless ballads adopt, and that’s one reason it translates so well across genres. If you ever leafed through sheet music for mid-century ballads, you recognize the signature climbs and rests—the way a bridge reframes the refrain so the return lands like a kept promise.

As for context: this recording sits within Buddy Holly’s exploration of orchestral pop at the tail end of the 1950s, a pivot from the sun-bright thrust of The Crickets to something that could sip a Manhattan in a hotel lounge and not feel underdressed. The label had a plan, the arranger had charts, and the singer had a voice that could hold still without turning static. That stillness has aged beautifully.

There is a paradox at the core of “True Love Ways.” It’s deeply personal and yet wholly public, a vow sung in a room full of strangers and microphones. The strings confer grandeur, but what lingers is the hush. Even the climactic swell refuses melodrama. The track never asks us to be impressed; it asks us to believe.

“Intimacy isn’t the absence of noise; it’s the courage to speak softly and trust that someone is listening.”

By the time the final cadence falls, you feel less like you’ve been entertained and more like you’ve been entrusted with something. Not just romantic devotion, but a mode of address the singer wanted to master: calm, grounded, unafraid of quiet. When he died, the narrative around his career froze too quickly around the early hits; the posthumous arrival of this recording nudged that frame a little wider. It said: here was also a man who could sit still and make stillness ring.

If you’re coming to “True Love Ways” for the first time, consider a focused listen. Let the first line meet you at a human distance, and imagine the space—the players arrayed, the conductor’s hand, the hall’s tall ceilings. Keep the volume modest; a vow should never have to shout. And if you’re returning after years away, you may hear your own life inside it now: the promises you kept, the ones you meant to, the way time asks for both patience and courage.

The legacy has only grown. Peter and Gordon’s 1965 rendition proved its cross-Atlantic appeal. Mickey Gilley’s 1980 cover reconceived it for a country audience without breaking the spell; a promise is a promise in any accent. But Buddy’s version remains the measure—the documentary truth of a room, a song, and a voice that understood the power of underlining a line by not underlining it at all.

That, ultimately, is why “True Love Ways” still calms a room. It reaches for something that pop often neglects: the blessed ordinariness of devotion, the steadiness of saying “always” softly. Call it a ballad, call it a standard-in-waiting, call it the most tender page of a short, brilliant career. In any case, it doesn’t need a superlative. It only needs a listener.

Sound Notes and Session Footprints:

Recorded October 21, 1958 at New York’s Pythian Temple with the Dick Jacobs orchestra, released posthumously on The Buddy Holly Story, Vol. 2; issued as a UK single in 1960 where it reached No. 25, and originally uncharted in the US. Personnel listings commonly include Al Caiola and Ernie Hayes among the session players. Coral is the label of record.

Historical Echoes:

Peter and Gordon’s version peaked at No. 2 in the UK and No. 14 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1965; Mickey Gilley’s country version topped the country chart in 1980. These aren’t just numbers—they’re waypoints that show how a quiet promise keeps finding new rooms to speak in.

And today? We still drop the needle—or tap play—and the room obliges. The voice steps closer. The strings step back. The promise lands.

One final contextual note for collectors: its first widespread presence for fans came on that posthumous album release, which has since become a shorthand for late Holly—proof that his sensibility stretched beyond teen-tilt rockers and into grown, candlelit spaces.

Listening Recommendations

Buddy Holly — Raining in My Heart — Same New York orchestral palette; strings and restraint drawing a circle around a tender vocal.

Buddy Holly — It Doesn’t Matter Anymore — A Paul Anka-penned ballad from the same session, with a lilting swing that shows the broader pop direction.

Roy Orbison — Crying — Early-’60s orchestral drama with a peerless vocal arc; the template for pop grandeur without bombast.

Elvis Presley — Love Me Tender — Minimalist devotion, a lesson in how quiet can carry the whole room.

Gerry & The Pacemakers — Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying — Mid-’60s pop balladry with brass and strings that nod toward the grown-up end of the decade.

Skeeter Davis — The End of the World — Country-pop melancholy, where simplicity, space, and sincerity do the heavy lifting.