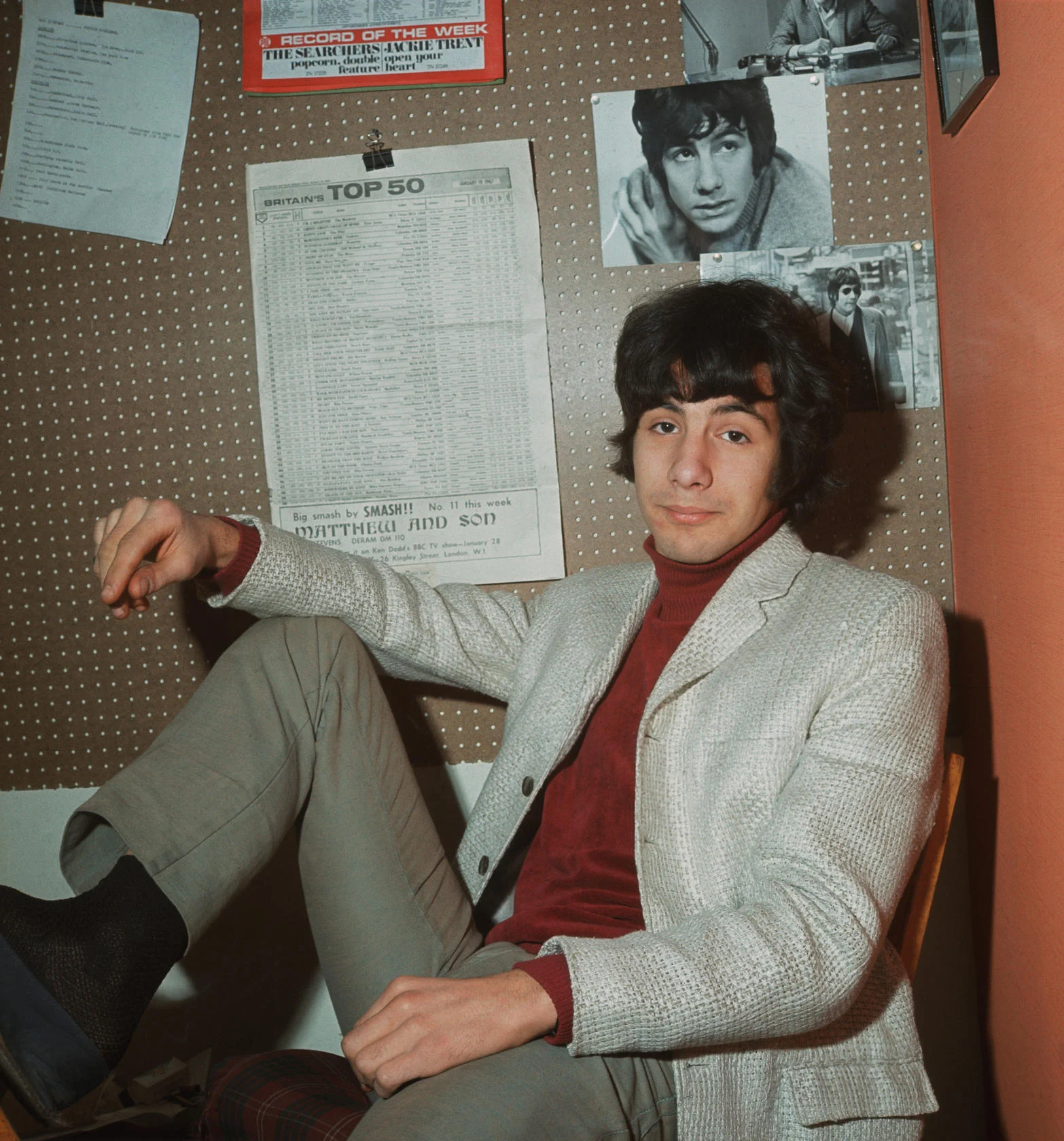

The year is 1966. London is humming, caught between the tail-end of Mod’s sharp lines and the coming psychedelic swirl. In a small recording studio, a young Greek-Cypriot songwriter named Steven Demetre Georgiou, already rebranded as Cat Stevens, is laying down a track that will launch his career far beyond the folk clubs of the West End. This is not the introspective, acoustic poet of the 1970s, nor the man who would later seek profound spiritual meaning in near-silence. This is a pop star in the making, and his weapon is a two-and-a-half-minute piece of music titled “Matthew And Son.”

I first encountered this single on a compilation of ’60s British hits, a cassette tape played constantly in my first car. It was always a moment of jarring brilliance between the familiar Merseybeat and the acid-laced psychedelia. Where I expected a simple strum, I got a curtain of lush, dramatic sound. It’s a song that deserves to be pulled out of the shadow of its younger, more famous siblings, Tea for the Tillerman and Teaser and the Firecat, and examined in the premium audio setting it deserves.

A Cinematic Score for the Cubicle Class

The track was released in December 1966 on the newly formed Deram label, a subsidiary of Decca known for its more eclectic or “avant-garde” releases. It was the second single from the soon-to-be-released debut album, also titled Matthew and Son (1967), and it rocketed up the UK charts, peaking near the very top. This success solidified Stevens’ initial arc as a baroque-pop sensation, a clever young man whose songs possessed a catchy swagger and a lyrical depth beyond the typical teenage fare.

The producer at the helm was Mike Hurst, formerly of The Springfields, who—alongside arranger Alan Tew—saw the inherent drama in the song. The core tension of “Matthew And Son” comes from this stunning contradiction: a cynical, almost Dickensian critique of monotonous corporate existence is dressed in the most opulent, glorious pop clothes imaginable.

The Arrangement: A Symphony of Ambition

Listen closely to the first few seconds. There’s a sharp, percussive flourish, a drum pattern that feels clipped and urgent, before the main body of instrumentation crashes in. It is a masterclass in mid-sixties orchestration. The textures are rich, almost theatrical. High, swirling strings dominate the mix, giving the song a sense of height and urgency, while the brass provides punchy, staccato accents. This is Baroque Pop distilled to a potent, commercially viable essence.

In the background, holding the melody together, is a surprisingly forceful rhythm section. Session luminary Nicky Hopkins handles the rapid, tumbling piano lines—a signature of the era’s sophisticated pop. Crucially, the propulsive bass line, reportedly played by a young John Paul Jones, drives the whole structure forward like a clockwork engine, adding a foundational weight that prevents the arrangement from floating away on the string section. Stevens’ own acoustic guitar is less about its folk timbre and more about percussive rhythm, blending into the background churn.

The vocals, delivered by the then-18-year-old Stevens, are full of youthful vibrato and a compellingly nasal English sneer. He’s telling a story, and the grand arrangement acts as the wide-screen backdrop for his narrow, miserable narrative. The mic feel is bright and clear, capturing every syllable of the corporate nightmare he describes.

The Shadow of the Desk Lamp

The lyrics themselves are where the song’s true brilliance lies. The protagonist is an anonymous cog, a worker whose existence is dictated by the titular firm. “He gets up each morning at half-past eight / He’s always at the office right on time.” It’s a story about the crushing routine, about the soul-death inherent in exchanging your life for a paycheck.

This theme, the weary resignation of the modern working man, feels strikingly mature for an artist so young. It’s a direct ancestor to later songs of alienation and routine. Yet, there’s a subtle, almost rebellious tone hidden within the polished delivery. The company profits from the sweat of the people, the son following the father, all trapped in an endless, generational cycle of drudgery.

“The true rebellion of the song lies in its ability to dress up profound existential dread as a joyous, three-minute pop singalong.”

When I listen to it now, I picture the scene: a gray, foggy London morning, a worker climbing the stairs to a dull, overheated office, while this incredible, over-the-top symphony swells in his head, a soundtrack to his quiet revolution. This piece of music captures the glamour and the grit of the Swinging Sixties simultaneously—the glamour of the orchestral studio, the grit of the life Stevens is singing about.

The Pivot Point

The success of “Matthew And Son” and his other early singles like “I Love My Dog” and “I’m Gonna Get Me A Gun” placed Cat Stevens firmly in the league of fashionable pop songwriters. His label, Deram, clearly envisioned him as a hit-making machine.

However, the intensive touring schedule and the pressure of this pop career ultimately took a heavy toll, leading to his severe bout of tuberculosis a couple of years later. That crucible of illness and reflection led to the dramatic pivot toward the stripped-down, philosophical sound that defined the next decade of his work.

Listening to this song is like looking at a photograph of the artist just before a profound, life-altering change. It shows us the path he almost took, a path of dramatic orchestral pop, far removed from the minimalist approach that would later make him a global superstar. The transition from the heavily produced, baroque sound of “Matthew And Son” to the intimate, finger-picked guitar and piano ballads of Mona Bone Jakon is one of the most significant stylistic shifts in pop history. This first hit, with its exuberant arrangement, serves as a dazzling, necessary contrast to the quiet depth that followed. The sheer commercial force of this track demonstrates the extent of his early talent, a talent that only needed to shed its orchestral skin to find its true, eternal voice. For anyone looking to understand the evolution of this extraordinary songwriter, getting into his earliest material, which often requires a music streaming subscription to fully explore the remastered versions, is essential.

Listening Recommendations: Follow the Strings and the Story

- “A Whiter Shade of Pale” – Procol Harum (1967): For a deeper dive into English baroque melancholy and dramatic organ work.

- “Eleanor Rigby” – The Beatles (1966): Shares the social commentary, telling micro-stories of isolation with a prominent, non-rock string section.

- “She’s Not There” – The Zombies (1964): Another example of a sophisticated British Invasion track powered by memorable minor-key piano.

- “Walk Away Renée” – The Left Banke (1966): The American zenith of Baroque Pop, defined by its delicate harpsichord and complex vocal arrangement.

- “Where Do The Children Play?” – Cat Stevens (1970): Listen immediately after “Matthew And Son” to fully grasp the stark, beautiful transition to the simpler, guitar-focused sound of his second career phase.