A song that took the scenic route to immortality

Every so often a record drifts into the world with little fanfare, only to find its voice—loudly—months or even years later. Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Game” is one of those rare pieces. Written by Isaak and produced by veteran American producer Erik Jacobsen, the track first appeared on Isaak’s third studio album, Heart Shaped World (1989). Released as a single in July 1989, it seemed destined to be another overlooked gem in Isaak’s catalog—until cinema intervened. When David Lynch used the song in his 1990 film Wild at Heart, it reframed the track as a kind of sonic dream: haunted, seductive, and impossible to shake. Radio stations took notice, audiences followed, and in January 1991 “Wicked Game” climbed into the U.S. Top 10, peaking at number six on the Billboard Hot 100. It also reached number one in Belgium and broke the Top 10 across several countries, including Germany and the UK. For Isaak, it was a breakthrough moment—the first hit of his career and the defining entry point to his singular world of late-night romance and pop noir.

The sound: minimalism with a mesmerizing pull

Part of the song’s power lies in just how little it needs to say so much. “Wicked Game” hinges on a spare, hypnotic progression most listeners can hum after a single play. It floats in a minor key, cycling through a simple pattern built to let silence do as much work as sound. Over that skeletal foundation, lead guitarist James Calvin Wilsey draws out a gliding, tremolo-kissed guitar line—an unforgettable motif that seems to shimmer like heat over a desert highway. There are no muscular drums, no towering crescendos, no complicated modulations. Instead, the arrangement uses negative space to build tension: a softly pulsing rhythm, faraway-sounding percussion, and a bass part that keeps everything grounded without ever distracting from the vocals.

Isaak’s performance is equally restrained. His voice, a satin croon with echoes of Roy Orbison, moves from chesty warmth to aching falsetto, never oversinging and never breaking the spell. He leans into each phrase with patience, letting words hang in the air like smoke. The production choices—light reverb, clear separation between instruments, tasteful echo around the vocal—add a cinematic scale without bloating the mix. It’s pop, but it’s pop that breathes.

Lyrical tension: desire, danger, and the fever of attraction

Lyrically, “Wicked Game” places us inside a moment when infatuation becomes perilous. The narrator is pulled toward someone he knows may undo him; seduction and self-preservation are at war. Isaak writes with clean, unadorned language, avoiding clever turns in favor of universal, elemental images—fire, fate, dreams, and the gravity of longing. Because the language is simple, the emotional frames do the heavy lifting. We understand at once that desire here is both irresistible and risky, and that the narrator knows it.

What makes the lyric endure is its economy. There are no detailed backstories, no moral lectures; just a slow confession that longing can be a trap you willingly spring on yourself. Paired with the music’s suspended stillness, the words feel like a heartbeat you cannot calm—a tension between wanting and warning that never resolves.

From sleeper to standard: the Lynch effect

“Wicked Game” might have remained a cult favorite if not for Wild at Heart. Lynch has a knack for finding songs that lodge themselves under a film’s skin, and here he pairs Isaak’s track with images that amplify its dreamstate quality. The film didn’t just expose the song to larger audiences—it altered how listeners heard it. Suddenly the track belonged to a bigger mood: mysterious, sultry, nocturnal. Radio programmers began spinning it; late-night request lines lit up. Within months, the single had crossed from a quiet album cut to a bona fide hit.

The trajectory is instructive. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, pop and rock landscapes were crowded with slick power ballads and neon-bright productions. “Wicked Game” cut through by moving in the opposite direction—quieter, slower, more cinematic. Its success signaled that listeners were hungry for space, atmosphere, and feeling over flash.

Two visions on film: Herb Ritts and David Lynch

Compounding the song’s rise were two distinct music videos, each expanding the track’s world in a different way.

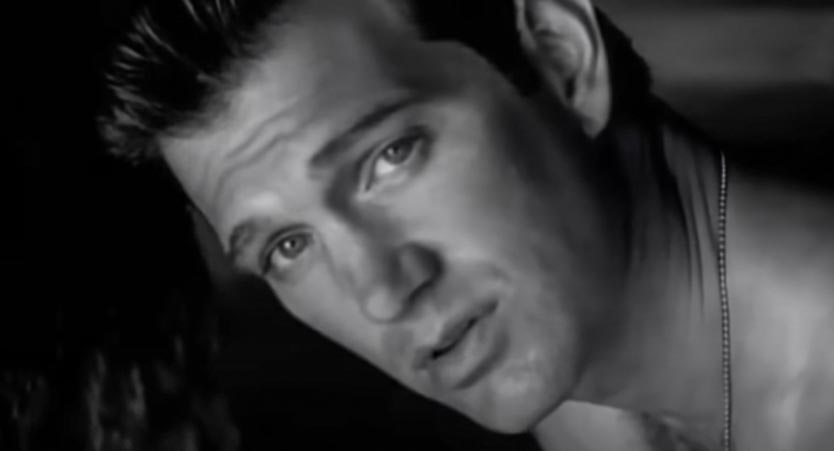

The most iconic version was directed by Herb Ritts and filmed on Kamoamoa Beach in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. The beach—newly formed by lava flowing from the Kīlauea volcano—gave the production a stark, primordial setting: dark sand, vast sky, foaming surf. Shot mostly in black and white, the video places Isaak and supermodel Helena Christensen in a minimal visual story of desire and distance. The camera lingers on gesture rather than plot: a look, a touch, a retreat. With its soft-contrast photography and sculptural framing, the clip became the visual counterpart to the song’s sound—sensual but melancholic, intimate yet mythic. It swept several MTV Video Music Awards (including Best Male Video, Best Cinematography, and Best Video from a Film) and would later earn top-tier placements on lists from VH1, Rolling Stone, and Fuse, frequently cited among the sexiest music videos ever made.

David Lynch also directed a separate video to accompany the Wild at Heart home release. Where Ritts chases timeless romance, Lynch leans into the eerie, gauzy mood that defines his cinema. Both clips, though, share a crucial understanding: “Wicked Game” functions best when the visuals give it room to haunt you rather than explain itself.

Inside the studio: producing a modern classic

Producer Erik Jacobsen’s touch is subtle but decisive. He keeps the palette narrow, favoring clarity over density. The drum sound is dry and intimate, the bass unshowy, the guitars clean but emotionally saturated—especially that tremolo lead, which seems to bend time as it swims in and out of the foreground. Nothing clashes; nothing shows off. Even the reverb is purposeful, placing Isaak just far enough from the listener to sound like a memory emerging in real time.

This is minimalism with intent. By reducing the arrangement to essentials, Jacobsen lets the core elements—melody, lyric, voice, and that spellbinding guitar figure—fill the frame. It’s an approach that has aged extraordinarily well. While many late-’80s productions feel tethered to their technologies, “Wicked Game” could be released tomorrow and sound current. The track’s restraint is its modernity.

The chordal hypnosis

Musicians often point to the song’s deceptively simple harmonic design as a key to its magnetism. A looping minor-key progression (commonly rendered by players as Bm–A–E) creates a sense of circular destiny—like walking the same shoreline again and again, hoping the tide will say something different this time. The melody rides that loop with small interval jumps and melted notes, leading to a chorus that doesn’t explode so much as deepen. It’s a masterclass in making repetition expressive: the longer it goes, the more it feels inevitable.

Why it connects: the psychology of the slow burn

Pop songs typically give us either the thrill of pursuit or the ache of regret. “Wicked Game” lives in the dangerous middle—when you know you’re crossing a line and do it anyway. The arrangement slows the clock so we can feel that micro-moment expand: the breath before a kiss, the thought you shouldn’t think, the step you can’t take back. Listeners from different eras and genres keep returning to it because that liminal space never goes out of style. Desire is always news.

There’s also a cinematic dimension to the track that invites personal projection. With so much sonic space, the listener’s own images rush in to fill it. That’s why the song works as well in a film scene as it does in a dim living room. It carries atmosphere with it, and atmosphere is endlessly adaptable.

Cultural footprint: from radio to runway to remakes

After the single’s chart run in the early ’90s, “Wicked Game” settled into a rare pop category: both ubiquitous and respected. It found long life on late-night radio formats, playlisted alongside torch songs and alt-pop ballads. Fashion houses and advertisers occasionally tapped its moody elegance. And artists across genres—rock, indie, metal, folk, even electronic—kept taking it apart and rebuilding it in their own image. Notable covers by acts like HIM, James Vincent McMorrow, and London Grammar underline just how versatile the composition is: strip it to acoustic bones and it becomes a confessional; drape it in electronics and it turns cinematic; feed it through heavy guitars and it becomes gothic romance.

Covers also spotlight the song’s melodic resilience. Many tracks collapse when you change their clothes; “Wicked Game” only seems to gain new shadows. That’s the mark of a standard.

On the album: Heart Shaped World as a frame

Although “Wicked Game” towers over Isaak’s catalog in public memory, it’s worth remembering the album that birthed it. Heart Shaped World is a carefully sequenced set that refines Isaak’s aesthetic—vintage rock and roll DNA, surf-guitar shimmer, ballads that ache without whining. Heard in context, “Wicked Game” is less an outlier and more a culmination. The record’s mood—lonely highways, neon flicker, the romance of the slightly broken—gives the hit a home. It also helps explain why Isaak’s career endured beyond a single chart triumph: the album world he builds is coherent enough to invite long stays.

The images we can’t forget

It’s impossible to separate the song’s identity from Herb Ritts’s visual language. The Ritts video distilled a certain early-’90s sensual minimalism: monochrome, windblown, elemental. Its staging on a black-sand beach—newly born of lava, later swallowed by the same force—adds a mythic undertone. Love as geology; desire as a landscape that remakes itself and erases its own evidence. Helena Christensen and Isaak give performances that feel both staged and spontaneous, like strangers learning a dance by instinct. The awards and “sexiest video” lists that followed weren’t just about glamour; they were acknowledgments of how perfectly the images matched the music’s temperature.

Lynch’s alternative video completes the diptych. If Ritts captured the romance, Lynch captured the spell. Together, they turned a three-minute song into a world you can visit.

What to listen for on repeat

If you’ve heard “Wicked Game” a thousand times, try these focal points on your next play:

-

The first guitar swell. That opening motif isn’t just a hook; it’s a thesis statement. Notice how the tremolo doesn’t wobble—it undulates, subtly changing depth to keep your ear leaning forward.

-

The vocal distance. Isaak often sounds a few feet away, as if you’re eavesdropping. The sonics make the lyric feel more intimate, not less.

-

The negative space. Pay attention to the rests. The silences after certain lines are as expressive as the lines themselves.

-

The chorus restraint. Where other ballads would surge, this one sinks—deeper into its own gravity. That inversion is part of its spell.

If you love “Wicked Game,” try these

-

Chris Isaak – “Blue Hotel”: The same lonely-glow atmosphere, with a more classic rockabilly lilt.

-

Chris Isaak – “Baby Did a Bad Bad Thing”: A darker, more driving cousin—sin, swagger, and cinematic punch.

-

Roy Orbison – “Crying”: The emotional ancestor; soaring croon, heartbreak rendered elegant.

-

Mazzy Star – “Fade Into You”: Hypnotic, hushed, and endlessly replayable; a ’90s dream-pop parallel.

-

The Righteous Brothers – “Unchained Melody”: Another timeless slow-burn that gives space to longing.

Why it still matters

More than three decades after its release, “Wicked Game” hasn’t faded into nostalgia. Its elements—the minimalist arrangement, the indelible guitar motif, the lyrical chiaroscuro, the iconic videos—cohere into a mood that feels perpetually contemporary. In an era when production trends shift by the month, this track’s refusal to chase fashion is its secret superpower. It’s not a museum piece; it’s a mirror. Listeners project their own stories onto it, and it reflects them back with elegance.

It also illustrates a larger truth about pop history: sometimes a song doesn’t need a marketing plan so much as the right context. A filmmaker hears it, a scene frames it, and suddenly the culture recognizes what was there all along. “Wicked Game” was always built to last—David Lynch and Herb Ritts merely turned up the lights so we could see it.

Final thoughts

“Wicked Game” is the sound of standing at the edge of something beautiful and perilous, knowing that stepping forward will change you. It is spare but lush, simple but inexhaustible, confident but wounded. It made Chris Isaak a star and gave the early ’90s one of its defining pop artifacts—a piece of music that feels like a night sky: empty at first glance, infinitely detailed the longer you look.

Put on Heart Shaped World, let that opening guitar ripple across the room, and listen to how desire learns to whisper. Then listen again. Some songs are built for the first impression. This one is built for the tenth.