The year is 1958. America is caught in a fascinating cultural torque—a pivot between the starched collars of its recent past and the loud, rebellious sprawl of its future. At the center of this exhilarating, often contradictory moment sits Chuck Berry, the sophisticated poet and itinerant preacher of a new gospel: rock and roll. His latest single for Chess Records, “Sweet Little Sixteen,” is not just a song; it’s a cinematic snapshot of an era, a three-minute document that somehow manages to distill the chaotic energy of thousands of teenaged lives into one perfect, coiled spring of sound.

I remember first hearing this piece of music not on vinyl, but shimmering through the cracked speaker of an old Wurlitzer jukebox in a diner that smelled perpetually of coffee and stale grease. The moment the needle dropped, the room seemed to acquire a faster pulse. That is the indelible power of a classic Berry track: it commands attention, not through orchestral sweep, but through pure, kinetic force.

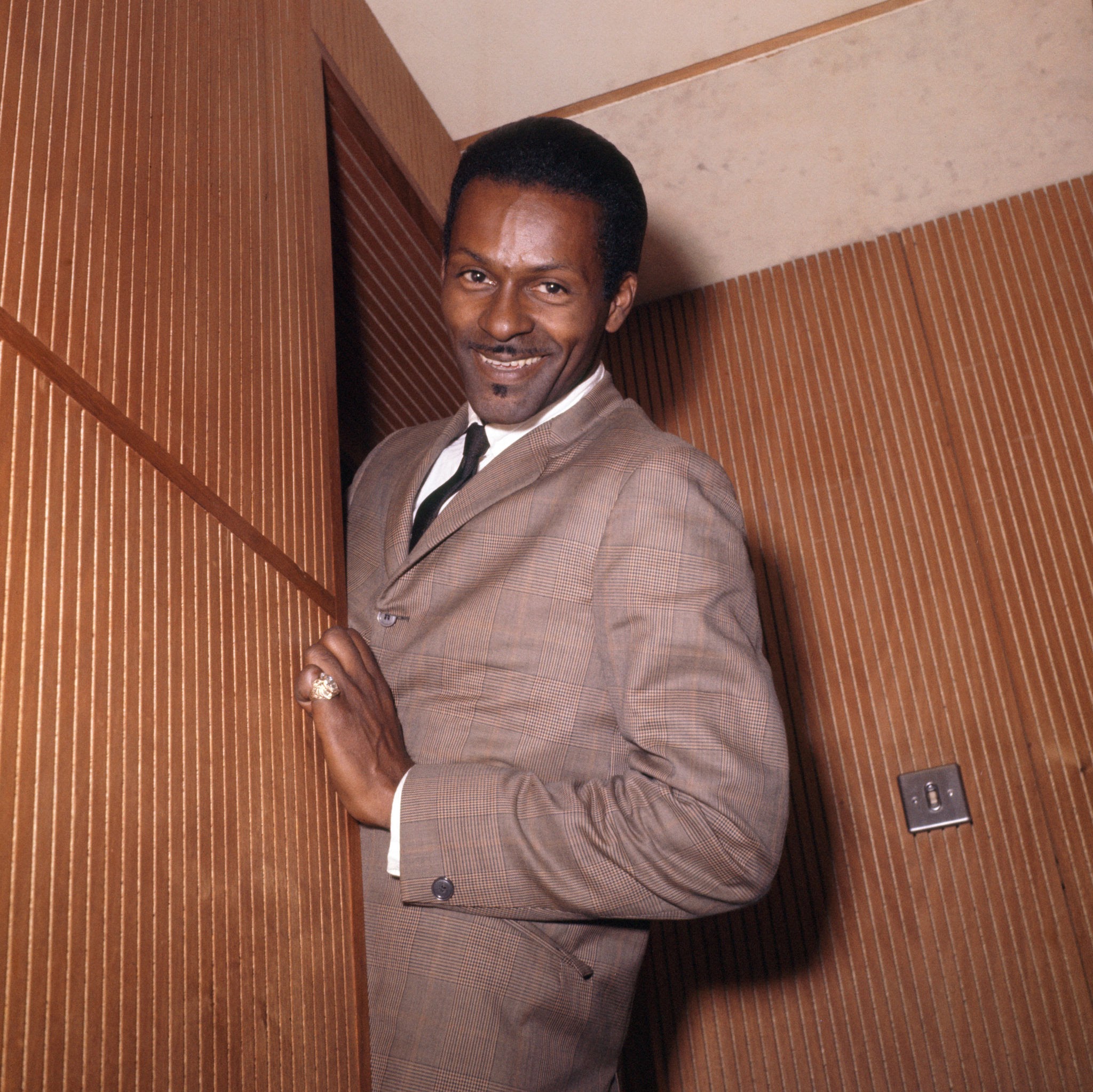

The Architect of Aspiration

By January 1958, when “Sweet Little Sixteen” was released, Chuck Berry was already a titan. Having landed multiple hits, including the genre-defining “Maybellene” and “School Day (Ring-Ring Goes the Bell),” he had cemented his role as rock and roll’s chief lyricist—the one who elevated songs about cars, girls, and school life into short, vivid stories. This track, reportedly inspired by a sight he witnessed after a concert in Denver, arrived precisely at the peak of his commercial and creative thrust, serving as a powerful prelude to the legendary “Johnny B. Goode,” which would follow later that year. Produced by the legendary Chess brothers, Leonard and Phil Chess, the recording bears the label’s distinct Chicago grit, a clean but not sanitized sound that perfectly complements the raw, focused energy of the band.

It’s important to acknowledge the album context of this crucial period. While initially issued as a single, the track was soon folded into his March 1958 album, One Dozen Berrys. More than just a collection of songs, this album showcased the remarkable consistency of Berry’s output, proving he was an artist capable of sustained pop dominance.

Anatomy of the Attack: Sound and Instrumentation

The structure of “Sweet Little Sixteen” is deceptively simple—a brisk, driving shuffle that adheres to the twelve-bar blues framework, yet feels entirely pop-ready. The song opens not with a bang, but with a breath: a short, sharp intake of air that cues the immediate entry of the rhythm section. The drum work is unfussy, locking into a steadfast backbeat that acts as the absolute bedrock, while the bass line, deep and mobile, glues everything to the floor.

Then comes the indispensable magic of the collaboration between Chuck Berry and his long-time partner, Johnnie Johnson. Johnson’s brilliant, rolling piano figures are the secondary engine of the song. They are not merely accompaniment; they are a constant, rippling counterpoint to the vocal and the guitar, providing the essential boogie-woogie pulse that links this new rock sound back to its rhythm and blues roots. Listen closely to the brief break where the piano takes the lead, an effortlessly cool flurry of notes that perfectly contrasts the sharp edges of the guitar. This masterful interplay is a clinic for anyone seeking advanced piano lessons.

Berry’s guitar performance on this track is one of his most iconic, a distilled essence of his genius. His famous double-stop intro riff, a sequence of notes played simultaneously on two strings, is instantly recognizable, a thrilling blend of country twang and blues phrasing. His solo, while brief, is a marvel of economy. It leaps out with a bright, clean timbre, each note articulated with a distinct attack and sustain, avoiding unnecessary flash for pure, melodic propulsion. This solo is pure narrative; it doesn’t wander. The acoustic space captured on the recording suggests a tight room, the close-miking allowing the percussive attack of the instruments to cut through with a palpable immediacy. Even today, listening to this on quality premium audio equipment reveals layers of detail in that rhythmic push and pull.

The Poet of Adolescence

What truly separates Berry from many of his contemporaries is his lyrical vision. He doesn’t just sing about teenagers; he adopts their vernacular, inhabiting their precise world with an ethnographic precision. The lyrics of “Sweet Little Sixteen” are a panoramic sweep of the early rock and roll circuit, moving from town to town—from Philadelphia, to St. Louis, to New Orleans—cataloging the anxieties and triumphs of a girl obsessed with meeting her favorite star. She is “tossin’ and turnin’,” “all dressed up like a queen,” and always “too young to be sixteen.”

This lyrical sophistication, blending high poetry with common slang, is why he is often called the genre’s first true poet laureate. He saw the glamour in the grit, the high drama in the mundane.

“Chuck Berry didn’t just write rock and roll songs; he wrote the script for the aspirational teenage experience, giving their fleeting moments of rebellion a sense of genuine, national importance.”

The tension in the song comes from this contrast: the girl’s frenzied, almost desperate search for connection with her idols, set against the track’s disciplined, airtight musical foundation. It’s a beautifully controlled chaos, much like the life of a teenager trying to navigate an adult world. He validates their desire to escape the confines of school and home, celebrating the communal, almost religious fervor of the concert hall. The song acts as a sonic bridge, connecting the regionalism of rhythm and blues to the unifying, national language of pop.

This narrative focus on the American teenager—their clothing, their rituals, their consumption of pop culture—was a direct line to his massive crossover success. He was telling stories about an experience that was rapidly becoming universal in the late 1950s, bridging the racial divides that still structured much of American life. The success of this single, reaching high on both the R&B Best Sellers chart and peaking at number two on the Billboard Hot 100, is quantifiable proof of that universal appeal. It was a shared soundtrack for a generation.

Even in our current age of fragmented music streaming subscription models, where discovery is algorithmically dictated, a song this vibrant cuts through. It is an artifact of pure, unadulterated excitement, a reminder that the best music is always about movement—physical, cultural, and emotional. It’s a story told with wit, precision, and an electric six-string that changed everything. The enduring simplicity and perfection of that guitar’s voice ensures that even over six decades later, the sweet, restless spirit of that sixteen-year-old girl is forever preserved on tape. It is, quite simply, an essential listen.

Listening Recommendations

- Chuck Berry – “Johnny B. Goode” (1958): The indispensable companion piece, featuring an even more frenetic, narrative-driven guitar performance.

- Little Richard – “Good Golly Miss Molly” (1958): Adjacent in release and comparable in its explosive, ecstatic energy driven by a relentless piano and vocal delivery.

- Buddy Holly – “Peggy Sue” (1957): Shares a similar focus on the themes of teenage obsession and features a tight, rhythmic arrangement.

- Bo Diddley – “Bo Diddley” (1955): An earlier Chess single that established the raw, rhythmic sophistication foundational to Berry’s style.

- Jerry Lee Lewis – “Great Balls of Fire” (1957): A high-octane track where the piano, much like Johnnie Johnson’s work here, acts as the primary source of kinetic chaos.

Video

Lyrics: Sweet Little Sixteen

They’re really rockin’ in Boston

In Pittsburgh, PA

Deep in the heart of Texas

And round the Frisco Bay

All over St. Louis

And down in New Orleans

All the cats wanna dance with

Sweet little sixteenSweet little sixteen

She’s just got to have

About a half a million

Framed autographs

Her wallet filled with pictures

She gets ’em one by one

Become so excited

Watch her, look at her run, boy“Oh mommy, mommy

Please may I go

It’s such a sight to see

Somebody steal the show

Oh daddy, daddy

I beg of you

Whisper to mommy

It’s all right with you”Cause they’ll be rockin’ on Bandstand

Philadelphia, PA

Deep in the heart of Texas

And round the Frisco Bay

All over St. Louis

Way down in New Orleans

All the cats wanna dance with

Sweet little sixteenCause they’ll be rockin’ on Bandstand

Philadelphia, PA

Deep in the heart of Texas

And round the Frisco Bay

All over St. Louis

Way down in New Orleans

All the cats wanna dance with, oh

Sweet little sixteenSweet little sixteen

She’s got the grown up blues

Tight dresses and lipstick

She’s sportin’ high heel shoes

Oh, but tomorrow morning

She’ll have to change her trend

And be sweet sixteen

And back in class againWell, they’ll be rockin’ in Boston

Pittsburgh, PA

Deep in the heart of Texas

And round the Frisco Bay

Way out in St. Louis

Way down to New Orleans

All the cats wanna dance with

Sweet little sixteen