There are songs that entertain, and then there are songs that travel with you. “City of New Orleans” belongs to the latter — a melody that hums like steel wheels on aging tracks, carrying stories of ordinary people across the wide American landscape. When Steve Goodman and John Prine sang it together, it became more than music. It became memory.

From the first gentle strum, the song feels like stepping onto a train platform at dawn. There’s a hush in the air, a sense of departure, and a quiet understanding that something beautiful is about to pass by. “Good morning America, how are ya?” isn’t just a lyric — it’s a question asked with affection, curiosity, and perhaps a touch of concern.

The Facts Behind the Folk Classic

Before diving into its emotional legacy, the historical details deserve their moment:

-

“City of New Orleans” was written in 1970 by Steve Goodman after he rode the Illinois Central line from Chicago to New Orleans.

-

The first major recording came from Arlo Guthrie in 1972, reaching No. 18 on the Billboard Hot 100.

-

Though John Prine never released a major charting version, his live performances with Goodman became beloved staples in the folk circuit.

-

In 1984, Willie Nelson brought the song to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot Country chart, introducing it to a new generation.

Yet charts and rankings only tell part of the story. The true heartbeat of the song lies in the friendship between two Chicago musicians who recognized something sacred in each other’s craft.

A Train Ride That Changed Everything

In 1970, passenger rail travel in America was fading. Highways were expanding, airports were booming, and the slow rhythm of train journeys felt like a relic. Goodman boarded the Illinois Central train with a notebook, wandering through its cars. He saw old men playing cards in the club car, mothers soothing restless children, workers quietly going about their duties.

What he captured was not simply scenery — it was transition.

Towns blurred past the windows like old photographs. Cornfields rolled endlessly. The train itself became a metaphor for a country moving forward while simultaneously losing pieces of itself. Goodman understood that progress often carries nostalgia in its shadow.

Legend has it that Goodman first tried to play the song for John Prine in a Chicago club. Prine, mid-conversation, jokingly brushed him off. Goodman later shared it with Arlo Guthrie, who immediately recognized its brilliance. But in time, it was Prine’s voice — warm, slightly weathered, deeply human — that would help cement the song’s emotional legacy.

When Two Voices Became One Memory

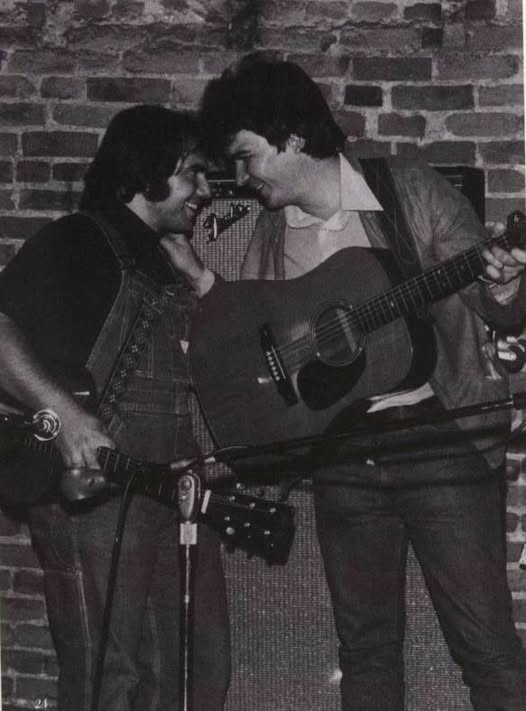

When Goodman and Prine stood side by side on stage, something remarkable happened. Their voices were distinct: Goodman’s tone bright and eager, Prine’s grounded and reflective. Yet together, they sounded like two sides of the same American story.

Their live renditions were never overly polished. They laughed. They improvised. They shared glances that only longtime friends understand. And in that informality, the song found new life.

They didn’t just perform “City of New Orleans.” They inhabited it.

For listeners, it felt like sitting on a porch at sunset while two old friends traded stories about the road. The train in the song wasn’t merely steel and smoke — it became a symbol of time itself. Always moving. Never stopping. Carrying memories in every car.

Why the Song Still Resonates

More than fifty years later, “City of New Orleans” still feels relevant. Why?

Because it speaks softly.

It doesn’t shout political slogans or demand attention. Instead, it paints portraits:

-

The old men in the club car.

-

The rhythm of wheels humming against rails.

-

The quiet dignity of workers keeping the train alive.

For older generations, the song can stir memories of long rail journeys and small towns that once felt like the center of the world. For younger listeners, it offers something rarer — a glimpse into a slower America, one where movement was measured in miles of track rather than flight schedules.

And then there’s that chorus — warm, open, almost hopeful. It greets the country not with cynicism, but with affection. Even as it acknowledges change, it refuses bitterness.

That balance — between melancholy and kindness — is perhaps why the song endures.

Willie Nelson and the Legacy Renewed

When Willie Nelson recorded his version in 1984, the song found fresh air in the country charts. His interpretation leaned into its storytelling roots, proving that great songwriting transcends genre. Folk, country, Americana — the labels mattered less than the sincerity.

By then, Goodman was battling leukemia, a fight he would ultimately lose in 1984. Yet his song lived on, traveling farther than any single train line could carry it.

John Prine continued performing it throughout his career, each rendition carrying both tribute and friendship within its chords. When Prine himself passed in 2020, fans returned to “City of New Orleans” as a place of comfort — a reminder that voices fade, but songs remain.

More Than a Folk Song

“City of New Orleans” is not simply about a train. It is about transition. It is about watching landscapes change through a window and realizing that time moves whether we’re ready or not.

It preserves small details — the kind that might otherwise disappear. And in doing so, it becomes a quiet act of resistance against forgetting.

There’s something profoundly human in its simplicity. No grand production tricks. No dramatic crescendos. Just a melody steady as rails and lyrics that feel like conversation.

In a world that often moves too fast, the song invites us to slow down — to notice who is sitting beside us, to listen to the hum beneath our feet, to greet the morning with a question rather than a complaint.

“Good morning America, how are ya?”

It’s still asking.

And perhaps that’s why the journey never truly ends. The train keeps rolling, the harmony lingers, and somewhere in the distance, two friends are still singing — not for fame, not for charts, but for the simple joy of telling a story worth remembering.

As long as there are tracks stretching toward the horizon and listeners willing to lean into nostalgia, “City of New Orleans” will continue its gentle passage through American hearts — steady, rhythmic, and full of grace.