The world outside the radio dial in 1973 felt loud—a cacophony of political turmoil, shifting social mores, and the lingering echoes of rock’s revolution. But when Conway Twitty’s voice cut through the static, everything hushed. It was the sound of a secret being whispered across a dimly lit room, a confession made at the edge of a precipice. The song was “You’ve Never Been This Far Before,” and it landed with the quiet force of a bomb, setting off a storm of moral outrage and undeniable commercial success.

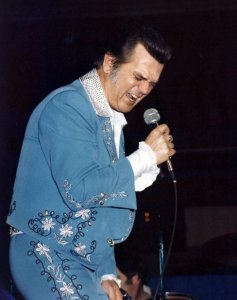

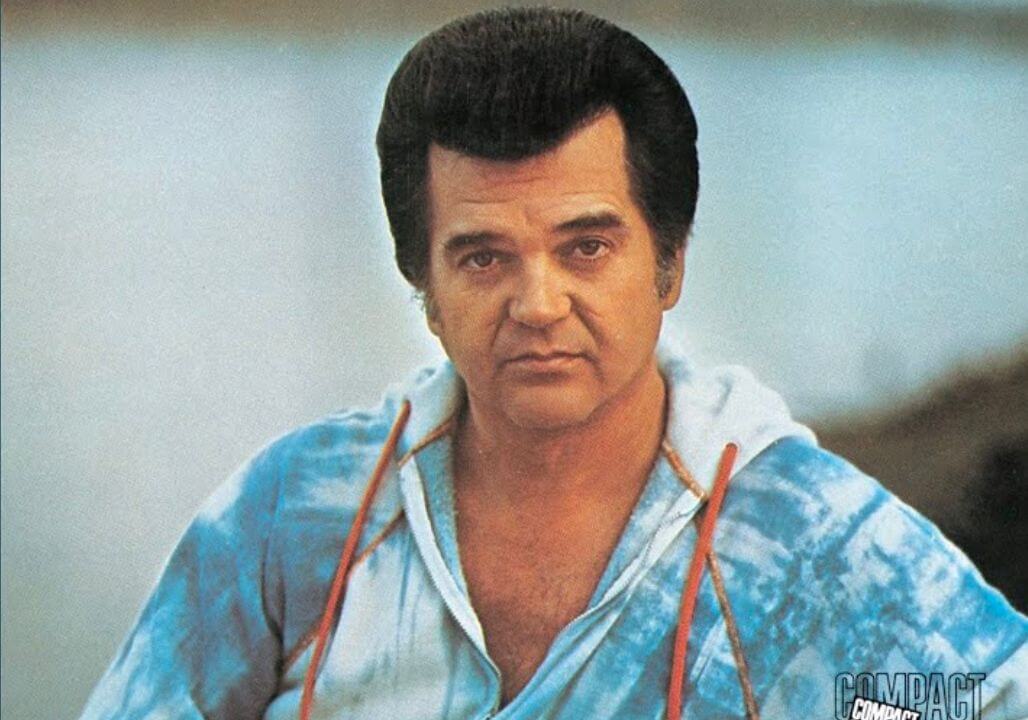

To understand this piece of music, you have to place it squarely within the career arc of Harold Lloyd Jenkins, the man who became Conway Twitty. By the early 1970s, the former rockabilly star had fully reinvented himself as Nashville’s premier purveyor of sensual, sophisticated country music. He wasn’t the swaggering outlaw; he was the mature man in the corner booth, offering understanding and a promise. This track, which he wrote and released on MCA Records, was the title track of his 1973 album of the same name. It represents the absolute pinnacle of his Countrypolitan era—a sound that polished away the grit of traditional honky-tonk while preserving the raw emotional core of its storytelling.

The single’s immediate controversy only amplified its reach. Certain, more conservative radio stations reportedly banned it outright, finding the lyrical content—a man reassuring a hesitant woman on the verge of a serious indiscretion—too suggestive for the airwaves. Yet, the public, hungry for stories that mirrored their own complex, imperfect lives, pushed it to the top. It became Twitty’s tenth number one on the US Hot Country Songs chart, but more remarkably, it crossed over, hitting the Top 40 of the Billboard Hot 100, a rare feat for a country single at that time.

The production of the track, handled by the legendary Owen Bradley, is where the genius of this piece resides. Bradley, architect of the “Nashville Sound,” understood that less was often more, especially when dealing with such highly charged material. The instrumentation doesn’t crash; it conspires. It’s a masterclass in controlled dynamics, designed not for the dance floor, but for the inside of a car late at night, or perhaps for listening on high-quality premium audio equipment.

The arrangement opens not with a bang, but with a deep, resonating electric guitar—not a twangy Telecaster riff, but a warm, sustained chord, establishing an atmosphere of nocturnal intimacy. This is quickly joined by a subdued rhythm section—the drums are brushed, not struck, giving the track a slow, deliberate heartbeat. The bass line is a deep, sensual anchor, moving with a velvety, unhurried grace.

Then comes Twitty. His voice, a low rumble that could go from a croon to a tear-soaked plea in a single breath, dominates the center of the mix. He employs his signature speaking-singing style, a theatrical device that breaks the fourth wall, making the listener feel like the direct recipient of his whispered counsel. “You’ve been telling me all night long / That you’d better be goin’ home…” The phrasing is deliberate, almost agonizingly slow. He holds the vibrato on certain words, stretching the tension like taffy.

A subtle but critical element is the role of the strings. They don’t swoop in the overblown manner of some mid-century pop; instead, they enter like a soft, breathy sigh. They are padding, a luxurious sonic blanket designed to mute the sound of the outside world. The strings follow Twitty’s vocal melody, rising slightly in pitch only when he reaches a high point of emotional intensity, such as the repeated, almost pleading question: “But you’ve never been this far before / And you don’t know the way.”

Underneath it all, a piano traces a simple, melancholic counter-melody. It’s not a showy solo, but a constant, slightly muted presence, adding an almost jazzy complexity to the country base. The textures are rich, almost tactile—you can practically feel the close mic capture, the warm tape saturation adding a vintage glow to the reverb trails. This controlled environment is critical; the emotional drama is all in the restraint.

The micro-story of this song lives on in contemporary life, far removed from 1973. Think of a late-twenties couple driving on a foggy highway, each hesitant about the road ahead—whether literal or relational. Or perhaps the quiet desperation of a listener who finds a certain kind of forbidden comfort in the song’s frank depiction of temptation.

“The genius of Owen Bradley’s production on this track is how he uses lush orchestration to create a feeling of absolute, devastating isolation.”

This approach to the arrangement creates a fascinating contrast. Lyrically, the song is stark, simple, and overtly sexual for its time; musically, it’s grand, orchestrated, and incredibly complex in its emotional layering. The high-stakes drama of the lyrics is wrapped in the soothing, enveloping sound of mature Nashville craftsmanship. It’s a study in control: Twitty’s vocal restraint contrasts with the volatile subject matter, allowing the listener to fill in the silence and the space. The success of this single proved that sophisticated, narrative-driven country music could not only court controversy but also conquer the pop market without sacrificing its soul. The song endures not because it was naughty, but because it was honest about a universal, confusing emotional space—the point of no return.

Listening Recommendations

- Tammy Wynette – ’Til I Can Make It On My Own (1976): Features a similar Countrypolitan string arrangement and a deeply personal, dramatic vocal confessional.

- Charlie Rich – Behind Closed Doors (1973): Shares the same year and the intimate, adult theme of a secret relationship rendered with smooth, orchestrated country soul.

- Glen Campbell – Wichita Lineman (1968): A brilliant example of the crossover Countrypolitan sound, using orchestral swells to enhance a solitary, poignant narrative.

- Joe Simon – The Chokin’ Kind (1969): A piece of deep, sultry Soul music that shares the same slow-burn, sensual vocal approach to a tale of relationship tension.

- Conway Twitty – Hello Darlin’ (1970): Twitty’s earlier classic that established his signature spoken-word, close-mic vocal style for relationship drama.

- Sammi Smith – Help Me Make It Through the Night (1971): A classic country story of fleeting intimacy, delivered with a world-weary and knowing vocal performance.

Video

Lyrics