Few rock anthems announce themselves with such clean, bright confidence as Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Up Around the Bend.” The first seconds—an instantly recognizable, high-register guitar call—operate like a porch light flashed across a dark highway, beckoning the listener forward. It’s a tight, compact record that reveals an entire musical worldview in under three minutes: no wasted notes, no indulgences, only propulsion. In the CCR canon, that combination of clarity and momentum is no accident; it reflects the band’s studio discipline during the era that produced Cosmo’s Factory (1970), the album on which “Up Around the Bend” ultimately appeared after its spring single release. If you want to understand why CCR represents the gold standard for economical American roots rock, start here—and then step into the larger room where this single lives, breathes, and still sounds brand new.

The Album Context: Inside Cosmo’s Factory

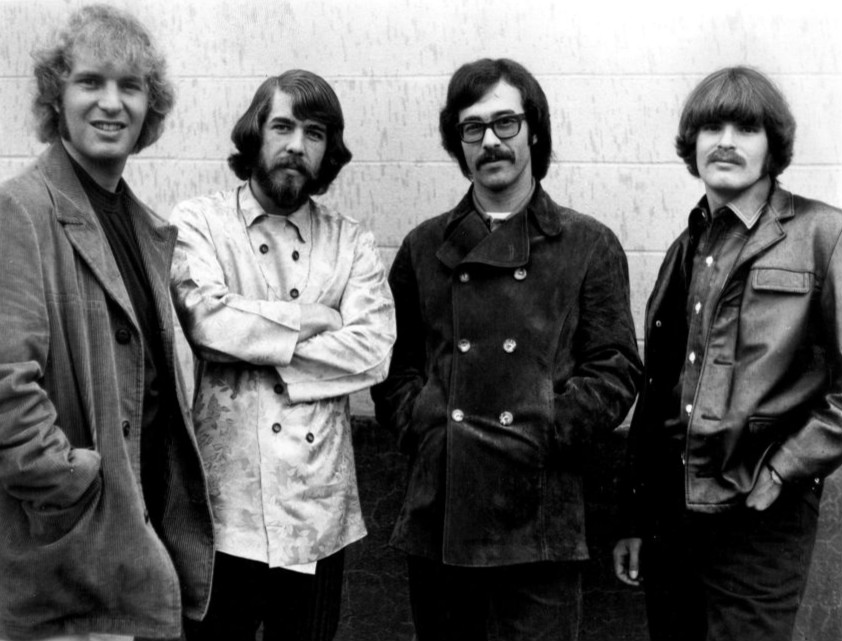

“Up Around the Bend” is most often encountered as the third track on side one of Cosmo’s Factory, a record that feels less like a conventional album and more like a curated tour of American popular music traditions—rockabilly flash, R&B pulse, blues grit, country twang, and swamp-rock humidity, all laid down with a blue-collar rigor. The title famously takes its name from the band’s relentless rehearsal schedule: drummer Doug “Cosmo” Clifford christened their rehearsal space the “factory,” and the nickname stuck, signaling the no-frills work ethic that runs through the LP.

As an album, Cosmo’s Factory is stacked with hits and signatures—“Travelin’ Band,” “Who’ll Stop the Rain,” “Run Through the Jungle,” “Looking Out My Back Door,” and “Long as I Can See the Light”—but “Up Around the Bend” holds a special place. Where some tracks lean into mythic melancholy or swampy menace, this one radiates optimism. It’s the record’s cleanest shot of daylight: brisk tempo, major-key brightness, and an outlook that invites motion. It also positions the album’s narrative arc, balancing good-time boogie with a kind of forward-looking Americana that’s never naïve. On Cosmo’s Factory, this track acts like a lighthouse; it sets your ear to CCR’s trademark blend of tight groove, plainspoken poetry, and unmistakable guitar color before you move into the album’s deeper waters.

The Sound Palette: Guitars That Ring, Rhythm That Drives

At the heart of “Up Around the Bend” is John Fogerty’s lead guitar tone: bright, cutting, and singing in the upper register. This is not fuzzed-out psychedelia, nor is it the crunchy mid-heavy bark you might associate with British hard rock. The timbre is almost bell-like, with enough edge to pierce the mix but not so much that it shreds the song’s tunefulness. The main riff is a model of brevity and clarity; it could serve as a blueprint for players seeking guitar lessons on how to build a memorable hook from a few well-chosen notes.

The arrangement is archetypal CCR: dual guitars (lead and rhythm), steady electric bass, and a locked drum kit. Rhythm guitarist Tom Fogerty provides the pocket’s plank—steady, unglamorous, essential—while Stu Cook’s bass part does something crucial that casual listeners may miss: it outlines the harmony with a swinging directness that keeps the tune buoyant rather than stiff. Doug Clifford, one of rock’s great “song-first” drummers, opts for a firm backbeat and crisp cymbal time, avoiding showy fills until they serve the vocal. This is a band that treats production like good carpentry—square cuts, tight joints, no rattles.

There’s not much in the way of studio wizardry here. If anything, the minimal effects sharpen the band’s virtues: clarity, blend, and air. You can hear space around the cymbals; you can feel the pick on the strings. The modest reverb and almost “direct-to-board” honesty underline something important about CCR’s aesthetic. They championed sound as a lived texture: the snap of the snare, the chime of the upper strings, the way backing vocals sit right behind John Fogerty’s impassioned lead. Though piano is not a foreground element on this track, the frequency balance leaves room for it; in a live setting, a keyboardist could double chords without clouding the image. This is why the phrase—piece of music, album, guitar, piano—can make sense here: the single functions as a modular, band-ready framework that welcomes added colors while remaining unmistakably itself.

Songwriting and Structure: A Call to Action in Three Minutes

Fogerty’s lyric approach is both populist and poetically efficient. The chorus offers an invitation—“Come on the risin’ wind”—that reads like a postcard from the near future. It urges you to move, not by explaining why you should, but by showing you the view when you arrive. Verses are plainspoken, almost aphoristic, punctuated by quick transitions back to that main guitar figure. What makes the structure so satisfying is the small harmonic “lift” between sections; the song pushes forward with each return to the riff, resetting your appetite in the same way a great short story resets your attention at each new paragraph.

Melodically, Fogerty keeps to ranges that emphasize urgency over ornament. The chorus sits at a reachable pitch for most rock singers, but the delivery amps the intensity—slight gravel, unforced vibrato, vowels that carry. Add the stacked backing vocals on key lines and you have a chorus that sounds bigger than the studio footprint. “Up Around the Bend” is proof that you don’t need modulation tricks or extended bridges to make a song feel expansive; you need a singular hook, a persuasive voice, and a band that knows when to leave air in the measure.

Performance: Vocals That Preach, Instruments That Witness

John Fogerty sings like a town crier who also happens to be a soul shouter. His phrasing is laced with gospel urgency—open vowels, clipped consonants, and a timing sense that hangs a fraction behind the beat to let the band pull him forward. Tom Fogerty’s rhythm guitar part is nearly percussive; it feels less strummed than stamped, which is one reason the groove never wobbles. Cook’s bass centers the harmony and occasionally nudges into little passing tones that prevent monotony, while Clifford’s drumming builds density by small degrees—slightly more open hi-hats, a firmer snare, just enough ride cymbal to suggest a gathering crowd. This is ensemble playing at its best: no passenger is idle, but nobody fights for the front seat.

The lead guitar break is short, tuneful, and conversational, functioning less as a showpiece and more as an extension of the main riff’s melodic logic. For players dissecting it in the shed—or inside music production software at home—it’s a masterclass in song-aware soloing: singable phrases, tasteful bends, and phrasing that honors the vocal line that came before it.

Production Values: Clarity as a Creative Choice

One reason “Up Around the Bend” feels timeless is the lack of era-stamped tricks. There’s no tape collage or studio gimmick that pins it to 1970. The production philosophy is literal: what the band played is what you hear. That “documentary” sonic lens is an artistic choice that aligns with CCR’s identity as chroniclers of the American imaginary—bayous and backroads, outlaws and working stiffs, sunlight and rain. When a record sounds this clear, the listener trusts it. And when the listener trusts it, the lyric’s invitation to head toward brighter horizons lands with more authority.

The mix prioritizes intelligibility. Lead vocal centered; guitars panned for separation without cartoonish width; bass warm but not swampy; drums framed by a modest room sound. If modern engineers are tempted to overcook the brightness to chase the shimmer of that opening riff, they should resist; the magic here is proportion. The record breathes because nothing is swollen. Even the handclap-like accents (likely tight snare strokes with sympathetic room reflections) are musical rather than flashy.

The Americana Thread: Country Roots in a Rock Framework

Although Creedence Clearwater Revival were a Bay Area band, their spiritual home has always been a composite of Southern musical traditions—country, blues, R&B, and rockabilly—filtered through John Fogerty’s pop instincts. You hear country’s economy and narrative directness in the lyric; you hear rockabilly’s snap in the guitar phrasing; you hear R&B’s dance logic in the rhythm section’s interlock. That blend is why CCR occupies a unique shelf: rugged enough for roadhouses, tuneful enough for AM radio, literate enough for critics, and fun enough for teenagers learning their first three chords.

In this sense, “Up Around the Bend” is a friendly cousin to the band’s darker “Run Through the Jungle” and the strutting “Travelin’ Band.” It lifts, whereas those grind or strut. If country and classical sensibilities sometimes meet in the ideal of “clear form,” CCR is one place they shake hands. Balanced phrases, development through repetition, a motif introduced and then restated with variation—these are classical virtues rendered in denim.

Themes and Imagery: The Cartography of Hope

The song’s central image—a literal or figurative bend in the road—doubles as a compact life philosophy. Fogerty doesn’t promise ease; he promises movement. The “rising wind” is more than scene-setting; it’s the weather of progress, the push you feel when you step into the unknown. Unlike protest-driven CCR classics that carry a palpable social charge (“Fortunate Son”), this lyric’s charge is motivational without being saccharine. It says: if you want the better view, keep walking.

One reason it resonates is that it sketches just enough detail to let listeners project their own destinations. For some, the bend is a new town, a new job, or a reunion; for others, it’s the moment a night drive delivers you to the glow of the next exit. The record is packed with kinectic verbs and forward-facing lines. Even the guitar’s upper-register melody feels like a hand pointing ahead.

Why It Endures: Utility, Identity, and Joy

Critics often overcomplicate the question of longevity. Songs last because they’re useful: to DJs, to filmmakers, to cover bands, to listeners who need a three-minute reset that feels like rolling down a window. “Up Around the Bend” is useful. It’s an opener, a closer, a driving song, a dance song, a song to test a new amplifier, a song to learn when your band needs something that will work in every bar in the United States and beyond. It’s also identity music. Within seconds, you can tell it’s CCR: that voice, that guitar light, that firm rhythm section, that ethos of clarity. Utility plus identity plus joy—that’s a durable triad.

The single’s compactness also means it never overstays its welcome. Radio loved it, and modern playlists still do, because it performs its function quickly and leaves listeners a little taller than it found them. Play it after a dirge and a room perks up; play it after a high-octane rocker and it still feels bigger because it’s cleaner.

Practical Takeaways for Musicians and Listeners

For players: dissect the arrangement. Notice how the rhythm guitar sets an even grain against the drums; how the bass keeps the harmony buoyant without stomping on the kick; how the lead lines avoid blues clichés in favor of melodic clarity. Try recording a cover with minimal effects and see how much of the magic comes from arrangement choices rather than plug-ins. For learners, those opening bars are an ideal study in right-hand consistency and left-hand economy—prime candidates for guitar lessons that focus on tone production through touch rather than gear.

For home-studio builders, the track is a template for gain staging and EQ restraint inside your music production software. High-pass the noise, tame the harshness, preserve the transient—then stop. Let the performance do the talking. The record’s longevity is a reminder that taste outlasts trend.

As a final note of terminology for readers who love cross-genre comparisons: while this recording is unabashedly guitar-driven, one could easily imagine a roots-piano arrangement doubling chords and percussive stabs live. That hybrid perspective is part of why this piece of music, album, guitar, piano conversation keeps surfacing in discussions about CCR’s adaptability on stage.

Listening Recommendations: If You Enjoy “Up Around the Bend”

If this track grabs you, move outward along the CCR constellation and then across the broader roots-rock sky:

-

Creedence Clearwater Revival – “Travelin’ Band”: A turbo-charged Little Richard homage with hornlike guitar phrasing and locomotive drums.

-

Creedence Clearwater Revival – “Looking Out My Back Door”: Country-inflected, porch-swing easy, proof of CCR’s gift for levity.

-

Creedence Clearwater Revival – “Green River”: Murkier bayou mood, a study in groove and imagery, with a hypnotic guitar pattern.

-

Creedence Clearwater Revival – “Bad Moon Rising”: Upbeat apocalypse; bright strumming meets dark prophecy—a perfect CCR paradox.

-

Creedence Clearwater Revival – “Who’ll Stop the Rain”: Lyrical, gently anthemic; the reflective counterpart to “Up Around the Bend.”

-

Lynyrd Skynyrd – “Sweet Home Alabama”: If you want a later-’70s vision of guitar-driven American roots rock with gleaming hooks.

-

The Band – “The Weight”: Rustic poetry and ensemble interplay; slower, but spiritually adjacent in its road-movie imagery.

-

The Rolling Stones – “Brown Sugar”: For a punchier, swaggering counterpoint with similar guitar brightness and rhythmic snap.

-

The Doobie Brothers – “China Grove”: Clean, percussive guitars and relentless forward motion; a 1970s cousin in spirit.

Queue those after Cosmo’s Factory and you’ll hear a larger conversation about how American music keeps finding new landscapes in familiar chords.

Final Verdict

“Up Around the Bend” distills Creedence Clearwater Revival’s essence: a direct invitation to motion, rendered with sparkling guitars, unwavering rhythm, and a vocal that preaches without sermonizing. Its place on Cosmo’s Factory underscores what made 1970 such a towering year for the band: they weren’t merely making collections of songs—they were shaping a vernacular, one that many players still speak and many listeners still crave. From the first chiming riff to the last joyful cadence, the track reminds us that rock’s purest power is not volume or virtuosity but direction. It points somewhere—toward the next town, the next chance, the next burst of sunlight. And every time the chorus returns, we go with it.