Few 1960s folk songs feel as effortless, as inevitable, as Donovan’s “Catch the Wind.” Released in 1965, it arrived with a hush rather than a bang—an intimate confessional whispered into the ear of a world suddenly overrun by amplifiers and feedback. The track’s staying power comes not from studio flash or a radical concept, but from its unguarded simplicity: a lone voice that sounds close enough to touch, a gently rocking guitar figure, and a melody that resolves like a long, deep breath. If you’re coming fresh to this classic, you’ll find it’s the kind of song that slows the room and sharpens the senses, even after decades of listening innovations and seismic shifts in popular music.

The Album Context: Two Titles, One Introduction to a New Voice

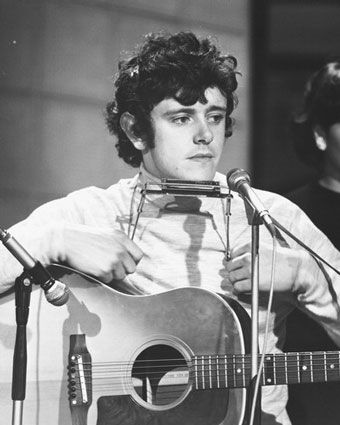

To understand “Catch the Wind,” it helps to place it on the album that first carried Donovan’s name into living rooms and record shops. In the U.K., that debut LP was called What’s Bin Did and What’s Bin Hid; in the U.S., it was retitled—more directly and strategically—Catch the Wind. The retitling does more than reflect marketing instincts; it reveals how central this song is to Donovan’s early identity. On the album, the track functions as a calling card for a young artist then introduced as Britain’s most promising folk troubadour. While the collection includes covers and original tunes that showcase Donovan’s grounding in traditional folk and blues, “Catch the Wind” stands out for its authorial poise. It is at once tender and assured, a quietly confident thesis that this new songwriter had something personal and durable to say.

That dual identity—U.K. album with a whimsical title, U.S. album anchored to the breakout single—also mirrors the artist’s range. Donovan was a sponge for American folk idioms, but he filtered them through a distinctly Celtic sensibility. Listen across the record and you’ll hear a songwriter steeped in ballad tradition, yet unafraid to shape his own lyrical world. The album remains a snapshot of that moment: a young voice stepping into the lineage of Woody Guthrie, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and Bob Dylan, but turning the camera slightly to capture a more inward light.

Instruments and Sound: Acoustic Poetry, Breath, and Space

“Catch the Wind” is, above all else, a masterclass in restraint. The arrangement is built around fingerpicked acoustic guitar and vocal, with harmonica appearing like a cool breeze that crosses the room and leaves just as gently. The guitar part outlines a lilting, waltz-like pulse—more sway than march—that gives the song its soft, spinning feel. Rather than driving the tempo, the right hand caresses it, and that touch allows the vocal to float on top. Donovan’s voice is close-mic’d, the breath on the microphone integral to the intimacy; a subtle reverb blooms at the ends of phrases, never distracting from the lyric’s lucid directness.

Bass and light percussion are used sparingly (depending on which version you hear), but the acoustic remains the anchor. If you’ve ever tried to reproduce the sound at home, you’ll notice how much depends on touch dynamics—the difference between nail and pad, the exact pressure of the left-hand chord, the measured release of the right-hand arpeggio. The harmonica’s timbre, meanwhile, is plain-spoken and human; it doesn’t dazzle with speed but sketches the contours of the melody like a pencil line that suggests, rather than insists upon, a horizon.

There are later versions—particularly the late-1960s re-recording—that add fuller arrangements, including tasteful strings to dignify the natural lyricism. Those renditions, while gorgeous, reinforce how thoroughly the core of the song lives in the simplest palette: voice, acoustic guitar, harmonica, and space. This is a piece that demonstrates how silence is not the absence of sound, but the frame that makes the sound glow.

Melody and Lyric: The Wind as Metaphor for Desire

The song’s metaphoric hook—trying to catch the wind—could easily lapse into cliché in lesser hands. Donovan avoids that trap because he grounds the image in sensory detail and human yearning. The words feel conversational (“In the chilly hours and minutes / Of uncertainty…”), yet the melody elevates them beyond speech. Pitches rise where longing tugs, then settle where acceptance waits; the contour is gentle, memorable, and singable. That singability matters: “Catch the Wind” is the sort of tune you hum without realizing it, as if the melody is an afterthought your heart makes while the mind lingers on something else.

The lyric’s architecture deserves attention. Rather than presenting a narrative arc, the song circles an emotion—the desire to hold what cannot be held. That circling mirrors the soft waltz feel; it’s as if the music and words agree that love is a dance you can’t step out of, even when you know that desire might not resolve into possession. The ending does not close the question; it embraces the paradox. As a listener, you feel seen but not preached to, which is one reason the piece still connects across generations.

Folk Roots, Country Echoes, and a Classical Sense of Line

Given Donovan’s international reputation as a folk icon, it’s easy to stop at “folk” as the genre label and move on. But “Catch the Wind” also resonates with a country-ballad tenderness: its open-voiced chords and waltz motion echo the shape of countless country laments. If you imagine a pedal steel drifting behind the vocal, you can hear how readily the song could stand alongside the gentler edge of 1960s Nashville.

At the same time, there’s a classical clarity in the melodic line—long-breathed phrases that arc like art song. The absence of ornamentation is classical in its discipline; each note seems chosen for inevitable purpose, like a well-placed brushstroke in a minimalist painting. This dual allegiance—country warmth and classical restraint—helps explain why so many listeners from different musical backgrounds hear themselves in it.

Production Touches: Analog Warmth, Mono Intimacy, and the Art of Not Overdoing

Part of the allure of the original recording is its analog warmth. Tape introduces a slight compression and saturation that flatters the acoustic guitar and thickens the vocal just enough to make the room disappear. The mono presentation folds the performance into a single, centered image. Instead of a wide soundstage, you get closeness—someone sitting in front of you and playing for you, not around you.

Notice the balance choices: the vocal never fights the guitar; the harmonica isn’t forced to the front as a stunt. It is, in production terms, an exercise in subtraction. Sometimes the greatest studio achievement is knowing what to leave out. “Catch the Wind” proves that absence can be a design principle, not a budget.

Tone Chasing: How to Approach the Song as a Player

If you’re a guitarist, the temptation is to ask which exact guitar and mic chain were used. That’s a fair question, but the heart of the tone is in the hands. A steel-string acoustic with moderate action and light-gauge strings often helps emulate the gentle top-end shimmer without sacrificing the warmth in the mids. Focus on the evenness of your fingerpicking—consistency across bass and treble voices—and on the controlled release of each note. Aim for low to moderate nail length; too long and the attack becomes glassy, too short and the articulation dulls.

Those interested in gear will inevitably consult lists of the best acoustic guitars, but it’s worth remembering that the recording’s eloquence has more to do with performance than price. An affordable, well-setup instrument, played with care and attention, will get you further than any high-end model played indifferently. If you sing while playing, practice separating breath from attack; the song’s intimacy relies on vocal phrasing that sits just inside the beat, never pushing.

Listening in the Present Day

In an era dominated by algorithmic playlists and compressed loudness races, “Catch the Wind” rewards focused listening. Try it with good headphones or through a modest hi-fi that emphasizes midrange clarity. You’ll notice micro-details—the slight inhalations before lines, the natural decay on sustained vowels—that digital perfection often sands away. If you’re exploring the song through music streaming services, seek out both the original single and the later re-recording. The juxtaposition underscores how the composition survives any framing; it is the songwriting, not just the sonics, that keeps the flame alive.

Why It Endures: Universality Without Platitude

Why do some songs feel permanent? In this case, it’s the combination of universal metaphor and personal delivery. The wind stands in for the beloved and for time itself—present, felt, but impossible to hold. The singer does not rage against that truth; he accepts it with wonder and a touch of melancholy. That posture is disarmingly mature for a young artist. Rather than dramatizing heartbreak, he names it quietly, and in doing so leaves room for the listener’s own experiences to enter. The result is a piece you return to when you need to feel more, not less, human.

A Note on “Piece of Music, Album, Guitar, Piano”

The song’s power also illustrates how categories intersect. As a “piece of music, album, guitar, piano” reference point, “Catch the Wind” lives in the pocket where songcraft, arrangement, and performance coalesce. Interestingly, there is no piano in the classic arrangement, yet the tune begs for a sparse piano rendition; you can imagine a single hand outlining the waltz pulse as the vocal floats above. That potential for re-interpretation is itself a measure of durability.

For Listeners Who Love Country and Classical

If your listening diet leans country, you’ll find kinship in the song’s plainspoken longing and its waltz sway; it sits comfortably alongside the gentler ballads in the American songbook. If you favor classical music, you’ll recognize the attention to line, the economy of means, and the way the melody’s architecture mirrors the text’s emotional arc. In both traditions, clarity of intention is prized—and “Catch the Wind” has that in abundance.

Recommended Listening: Songs That Share the Air

After you spend time with “Catch the Wind,” you may want to live in that mood a little longer. Here are several songs and performances that keep the same air in their lungs:

-

Donovan – “Colours”: Another early Donovan gem, using similarly spare instrumentation to explore emotional universals.

-

Bob Dylan – “Girl from the North Country”: Fingerpicked elegance, delicate phrasing, and a wistful gaze across a landscape of memory.

-

Gordon Lightfoot – “Early Morning Rain”: Folk storytelling with a country heartbeat; melancholic but inviting.

-

Simon & Garfunkel – “Kathy’s Song”: Intimate guitar-and-voice poetry, recorded with the gentleness of a letter never meant to be sent.

-

Tim Hardin – “Reason to Believe”: A masterclass in directness, with the same refusal to overstate.

-

Bert Jansch – “Needle of Death”: Harmonically richer and darker in theme, yet guided by the same belief in the guitar’s quiet authority.

-

Joan Baez – “Diamonds & Rust”: Later in the decade, but the reflective lyricism and unvarnished vocal feel aligned with Donovan’s sensibility.

Each of these tracks proves, in its own way, that understatement can be a kind of bravado—that confidence in the song itself can outshine any studio spectacle.

Final Thoughts: The Wind You Can’t Hold—And Why That’s Perfect

“Catch the Wind” continues to matter because it dignifies the unsayable. It doesn’t promise that love will be mastered, only that it will be honored. The arrangement—acoustic guitar, harmonica, voice—isn’t just a style; it is a philosophy of listening. By leaving room for breath and silence, the recording invites you to complete the picture with your own feelings. As a listener, you become a participant rather than a consumer.

The album that presented it to the world—What’s Bin Did and What’s Bin Hid in the U.K., Catch the Wind in the U.S.—still reads like a doorway. Step through and you’ll find an artist learning how little is needed to tell the truth. You’ll also find the template for countless singer-songwriters who followed: keep the melody honest, keep the words clear, and let the performance be a conversation rather than a speech.

If you’re a player, the lesson is equally direct. Your guitar is a storyteller; let it whisper. If you’re a singer, rely on phrasing over force. If you’re a listener, give the song your attention and it will repay you with quiet revelations. And if you’re a collector or explorer of recordings, compare versions to notice how arrangement shapes perception—another reminder of how a single composition can wear different clothes and remain utterly itself.

More than half a century on, “Catch the Wind” is not a relic; it’s a living companion. It turns the everyday act of longing into a moment of grace, and then it leaves the door open so the wind can come and go, as it always has and always will. In a world that often confuses volume with meaning, Donovan’s classic stands as proof that the softest voice in the room can tell the deepest truth—no album-length argument required, just one perfectly formed song.