Before Dwight Yoakam became a Grammy-winning country icon with a sound instantly recognizable from the first twang of a guitar, he was grinding it out in places most stars never mention — smoky bars, half-empty clubs, and rowdy venues where country music wasn’t exactly welcome. Long before the spotlight found him, Yoakam was already shaping a style that refused to fit neatly into Nashville’s polished mold. What looked like an uphill battle at the time would later be seen as the very thing that saved his career — and helped revive traditional country music for a new generation.

Born in Pikeville, Kentucky, and raised in Columbus, Ohio, Yoakam grew up surrounded by the echoes of classic country legends. Buck Owens, Merle Haggard, and Johnny Cash poured through radios and jukeboxes, leaving a permanent imprint on his musical DNA. But he also absorbed rock ‘n’ roll, rhythm & blues, and the restless energy of youth culture. That blend — traditional roots mixed with rebellious edge — would become his signature.

By the late 1970s, Yoakam made a bold move that many thought made no sense: he headed west to Los Angeles. Nashville, the heart of country music, was drifting toward smoother, pop-leaning production. Yoakam’s raw, honky-tonk revivalism didn’t match what Music Row executives were selling. Instead of compromising, he carved out his own lane in the unlikeliest of places — the L.A. club scene.

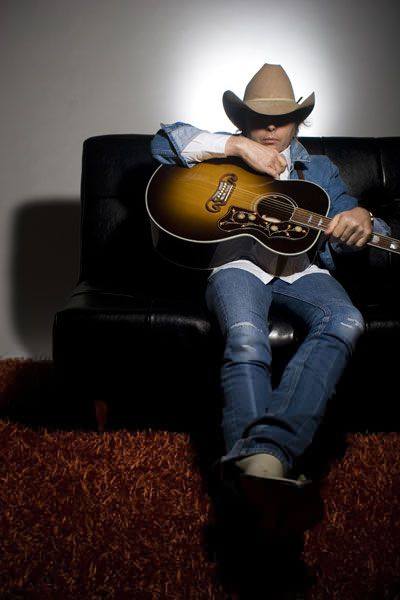

There, between punk bands and rock acts, Yoakam took the stage in tight jeans, a cowboy hat, and unapologetic country swagger. The contrast was electric. Audiences who had never given country music a second thought suddenly found themselves hooked on Bakersfield-inspired twang delivered with rock-club intensity. His shows were loud, fast, and full of attitude, but beneath the energy was deep respect for the genre’s roots. He wasn’t parodying country — he was resurrecting it.

That gamble paid off in 1986 with the release of his debut album, Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc. The title alone sounded like a mission statement. Packed with driving rhythms, Telecaster bite, and Yoakam’s distinctive high, lonesome drawl, the record exploded onto the scene. Covers like “Honky Tonk Man” sat comfortably beside originals like “Guitars, Cadillacs,” proving he could honor the past while pushing the sound forward. Critics hailed him as a breath of fresh air, and fans hungry for something real finally had a new hero.

The album didn’t just succeed — it shifted the conversation. Suddenly, the stripped-down Bakersfield sound pioneered by Buck Owens and Merle Haggard felt modern again. Yoakam wasn’t following trends; he was resetting them.

He proved it wasn’t luck with a string of powerhouse follow-ups. Hillbilly Deluxe delivered hits like “Little Sister” and “Little Ways,” cementing his place on country radio without sacrificing edge. Then came Buenas Noches from a Lonely Room, an album that balanced heartbreak and attitude with stunning control. Songs like “I Sang Dixie” revealed a vulnerability beneath the swagger, while “Streets of Bakersfield,” his duet with Buck Owens, became both a chart-topper and a symbolic passing of the torch between generations of honky-tonk rebels.

What made Yoakam stand out wasn’t just the music — it was the total package. His image felt timeless yet fresh: part rockabilly cool, part Kentucky grit. He moved onstage with the confidence of a rock star but sang with the emotional precision of a classic country storyteller. Heartache, humor, loneliness, and defiance all lived in his voice.

Through the 1990s, he continued to evolve. Tracks like “Ain’t That Lonely Yet” and “Fast as You” showed he could blend polished production with traditional sensibilities without losing authenticity. While many artists chased crossover trends, Yoakam stayed grounded in storytelling and musicianship. Even when his sound incorporated bluegrass textures, rock influences, or Americana shades, the core remained unmistakably country.

But Yoakam’s creativity wasn’t limited to music. He built a respected second career in film, surprising audiences with nuanced performances in movies like Sling Blade, where he played a chillingly volatile character, and later in Panic Room and other roles. Acting revealed another dimension of his artistry — a willingness to take risks and avoid being typecast. Much like his music, his film choices leaned toward character, depth, and unpredictability.

Despite decades in the industry, Yoakam never became a nostalgia act. He continued recording, touring, and experimenting, all while maintaining the integrity that defined his earliest days. His live shows still carry the same urgency he brought to those L.A. clubs, a reminder that his career wasn’t built on hype — it was built on conviction.

Looking back, Dwight Yoakam’s journey reads like a blueprint for artistic independence. When Nashville wasn’t ready, he didn’t soften his edges — he found a new audience. When trends shifted, he didn’t chase them — he doubled down on what made him different. In doing so, he helped lead the neo-traditionalist movement that brought steel guitars, honky-tonk rhythms, and emotional honesty back to the forefront of country music.

His influence can be heard in countless modern artists who blend classic country textures with contemporary energy. Yet few can match the singular mix of style, grit, and authenticity that Yoakam brought to the table from day one.

From dimly lit bars to sold-out arenas, Dwight Yoakam’s story isn’t just about fame. It’s about staying true to a sound when the world says it’s outdated, about honoring tradition without becoming trapped by it, and about proving that real music — played with heart and conviction — never goes out of style.

And every time that sharp guitar riff kicks in and that unmistakable voice cuts through the speakers, it’s clear: Dwight Yoakam didn’t just make country music history. He helped rewrite its future.