In the polished, radio-friendly world of mainstream country music, few stories feel as satisfyingly rebellious as Dwight Yoakam’s rise to fame. Today, he’s celebrated as a trailblazer, a Grammy winner, and one of the leading figures of the neotraditionalist movement. But before the accolades, platinum records, and sold-out tours, Yoakam was something Nashville didn’t want. Too country. Too old-school. Too different.

And that rejection didn’t end his career — it defined it.

A Misfit in Music City

When Dwight Yoakam first set his sights on Nashville in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the city was riding a commercial wave. Country music was leaning toward crossover appeal, shaped by the “Urban Cowboy” era. Smooth production, pop influences, and radio-friendly polish dominated the airwaves. Artists were styled for mass consumption, and traditional honky-tonk grit had largely been pushed aside.

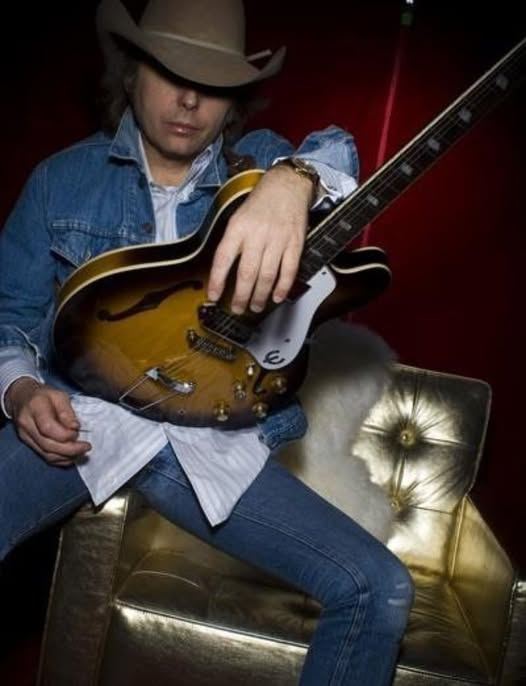

Into this landscape walked Yoakam — skinny, intense, dressed in tight jeans, a cowboy hat, and a vintage denim jacket. But more striking than his look was his sound. He wasn’t chasing trends; he was chasing ghosts — the sharp twang of Buck Owens, the Bakersfield drive of Merle Haggard, the emotional directness of classic West Coast country.

To Nashville executives, he didn’t sound like the future. He sounded like the past.

And that, ironically, was the problem.

“You’re Too Country”

Yoakam has spoken openly over the years about those early meetings and auditions that went nowhere. Record labels weren’t just hesitant — they were dismissive. The message he heard again and again was blunt: There’s no place for this on country radio. Some reportedly told him his music was “too retro.” Others felt his stripped-down sound couldn’t compete with the slick production dominating the charts.

Imagine being told you are too country for the country music industry.

For many artists, that kind of wall would force a compromise. Soften the twang. Add strings. Chase a more commercial sound. But Dwight Yoakam wasn’t interested in sanding down the edges that made him who he was. He believed country music’s roots weren’t outdated — they were timeless.

So instead of changing his sound, he changed his location.

Los Angeles: An Unlikely Home for Honky-Tonk

In a move that seemed almost backward at the time, Yoakam left Nashville and headed west to Los Angeles. It wasn’t exactly known as a country stronghold. But L.A. in the early 1980s had something Nashville didn’t: a thriving roots-rock and punk scene that valued authenticity over format.

Yoakam began performing in clubs alongside bands like The Blasters and Los Lobos. These crowds didn’t care about genre boundaries. They responded to energy, honesty, and attitude — all things Yoakam had in spades. His Bakersfield-inspired sound, driven by sharp Telecaster guitar and dancehall rhythms, suddenly felt fresh rather than outdated.

In smoky bars and small venues, he built a devoted following the old-fashioned way: one electrifying live show at a time. His music carried the emotional punch of classic country but the rebellious spirit of rock ’n’ roll. That combination resonated far beyond traditional country audiences.

Ironically, it took leaving the heart of country music to prove that his version of country still had a heartbeat.

Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc. — A Shot Heard in Nashville

By the time Yoakam released his debut album, Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc., in 1986, he had already developed a reputation as an outsider with serious momentum. The record wasn’t a compromise — it was a declaration. From the title track’s driving rhythm to his revival of Johnny Horton’s “Honky Tonk Man,” the album sounded like it had been beamed in from a honky-tonk in 1965, but with modern fire and urgency.

Listeners loved it.

The album became both a critical and commercial success, climbing the charts and earning widespread praise for reviving a raw, traditional sound many fans didn’t realize they’d been missing. Country radio — the same gatekeeper that once shut him out — suddenly couldn’t ignore him.

Yoakam’s success helped ignite what became known as the “New Traditionalist” movement, paving the way for artists like Randy Travis, George Strait, and later Alan Jackson to bring classic country elements back into the mainstream. Nashville hadn’t just misjudged Yoakam — it had misjudged the audience.

Integrity Over Acceptance

What makes Dwight Yoakam’s story endure isn’t just that he eventually succeeded. It’s how he succeeded. He didn’t bend to fit the system. He built momentum outside it until the system had no choice but to pay attention.

His journey is a case study in artistic conviction. At a time when the industry was chasing broader markets, Yoakam doubled down on specificity. He believed that emotional truth and musical heritage weren’t limitations — they were strengths. By trusting that belief, he reshaped the genre he loved.

He also redefined what it meant to be a country artist. You didn’t have to follow Nashville’s formula. You could draw from tradition without sounding dated. You could honor the past while still sounding urgent and alive.

The Legacy of a Rejection

Today, Dwight Yoakam is rightly viewed as one of country music’s most important modern traditionalists. His influence stretches across decades, and his catalog remains a touchstone for artists who value roots over trends. But it all traces back to a moment when the industry told him “no.”

That rejection, painful as it must have been, became the spark that pushed him toward a more independent path — one that ultimately expanded country music’s possibilities. It’s a reminder that gatekeepers don’t always recognize the future when they hear it, especially if it sounds like the past.

In the end, Dwight Yoakam didn’t just survive being rejected by Nashville. He forced Nashville to rediscover part of itself.

And country music is richer for it.