I keep hearing the click of a tape machine before the music starts—an imaginary cue, the kind you feel in your bones rather than in your ears. The room is modest, the air a little dry, and the meters barely settle before the band jumps. Suddenly, there’s a compact blast of rhythm, a sun-flare of treble, and a voice that sounds like it’s standing right in front of you, shirtsleeves rolled, knowing grin loaded. “C’mon Everybody,” from 1958, announces itself in a single breath like a car door slamming before the night’s first joyride.

Though remembered as one of the great rockabilly anthems, the track was a single first and foremost—issued by Liberty Records, co-written by Eddie Cochran and his manager Jerry Capehart—and only later folded into compilations, including The Eddie Cochran Memorial Album after his untimely death. That chronology matters. “C’mon Everybody” wasn’t designed to be a deep cut tucked between ballads; it was built to stand alone on a 45, to be pulled from a diner’s jukebox or a teenager’s portable turntable and to set an immediate mood: motion.

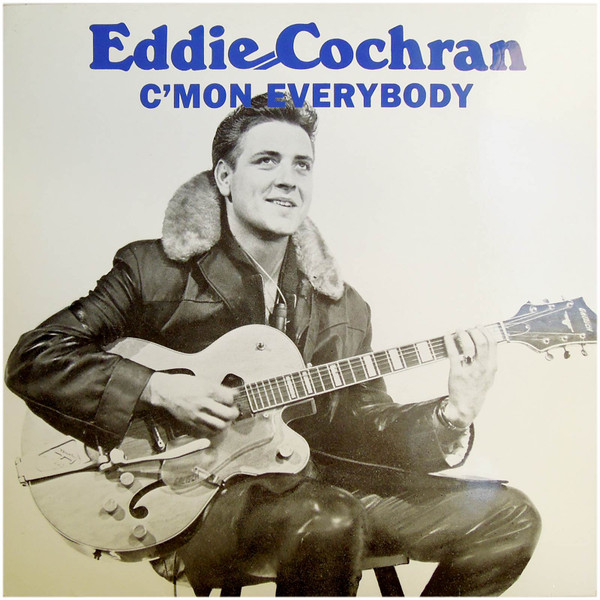

Cochran’s career in 1958 was gathering steam. He had already carved out a reputation as a versatile young American rocker who could sing, write, and—crucially—shape the studio sound around him. Accounts vary on the precise production credits, as was often the case in that era, but the record bears his fingerprints: the punchy arrangement, the brash confidence, the sense that the singer understands what the microphone wants. You can hear the self-assurance of a 20-year-old who was already behaving like a studio captain.

What strikes me first today isn’t nostalgia; it’s efficiency. Every sound has a job. The rhythm section doesn’t drag; it leans. The bass walks with a touch of bounce, the drums push straight ahead, and a rasping, bright lead line slices through like a grin you can hear. There’s a bit of slapback echo—short, taut, decisive—conjuring spatial depth without washing anything out. The mono image is narrow by modern standards, yet the record feels roomy, as if the walls themselves are pulsing in time.

Listen for the arrangement’s little pivots. Stop-time breaks, those quick drops where the band holds its breath, set up the chorus like a springboard. Background shouts and stacked voices act as a crowd forming instantly, a sonic line outside the door that tells you the party has already started. This is teen-energy handed a microphone: not immature, not naïve—just urgent. Cochran’s vocal rides just above the band, neither crooned nor barked, with a relaxed enunciation that keeps the celebration from tipping into chaos.

The lyric concept is simple: get together, make a little noise, claim your own night. But the phrasing nudges it from slogan to scene. Cochran doesn’t preach; he hosts. He’s the friend who knows the right house, who brought the records, who says “c’mon” and actually means it, no subtext. And because the verses sketch such a clear image—parents out, furniture pushed, dance floor invented—the track doubles as a micro-movie of teenage America in the late fifties, where independence was measured in borrowed time and borrowed rooms.

If you’re attuned to period recordings, the mic character is a delight. The vocal sits close, dry enough to catch a faint edge of breath, then shadowed by that quick echo that returns like a wink. The snare has a papery crack, the kick a compact thump, and the cymbals are mixed with restraint so that the pulse stays centered. There’s little low-end smear, suggesting careful placement rather than brute force. It’s concise engineering: the soundstage is a small town, the dynamics a main street at dusk, everything ready to move.

I’ve always loved the way the track passes the baton from verse to chorus. The band’s energy compresses, then rebounds; the crowd vocals answer, not as choir but as co-conspirators. That call-and-response isn’t gospel in form, yet it borrows the same communal electricity. You are not just hearing a performance; you’re being drafted into it. And that may be the oldest trick in rock and roll—turn the listener into a participant, a warm body in the room.

As a piece of music, “C’mon Everybody” is deceptively sturdy. The chord pattern is straightforward, almost skeletal, which grants the performance enormous flexibility. You could pull the tempo a notch slower and it might swagger; push it faster and it would scream. Cochran lands right in the sweet spot—fast enough for kinetic excitement, controlled enough to stay intelligible. The economy of the structure lets the vocal punctuations and instrumental interjections matter. Nothing is ornamental; everything is functional.

The instrumental colors are classic rockabilly. A bright lead cuts across the top of the mix with quicksilver runs and pointillist accents. You hear short, almost clipped phrases that bloom and vanish before they overstay. There’s warmth in the midrange but very little haze, which keeps rhythmic details crisp. For a moment in the middle eight, the band feels like it’s leaning forward on its toes, catching the chorus before it even arrives. The momentum is that physical.

One detail that often goes unremarked: the absence of ornate keyboards in the arrangement. A bar-room piano would have tipped the texture toward boogie; keeping it minimal preserves the record’s inhale-exhale precision. The discipline pays off when the final chorus lands and the voices widen. You get a broader impression without any single element blasting beyond its weight class. It’s the difference between teenage mayhem and teenage command.

Cultural context helps explain the song’s durable grin. In the U.S., it turned heads; in Britain, it became a genuine hit and would later echo across the early sixties when British groups studied American singles like textbooks. Cochran’s catalog never sprawled across decades the way some contemporaries’ did—his life was heartbreakingly brief—but his impact radiated outward: onstage swagger, studio smarts, the idea that a young artist could both front the performance and steer the console.

There’s an almost cinematic quality to the recording that modern listeners sometimes miss. You can imagine the room: a small crew, head-nodding engineers, a red light above the door, the sort of place where a singer measures the distance to the mic with a glance and a habit. The take doesn’t feel labored; it feels chosen. And because it’s chosen, it has that mysterious “rightness,” the quality that makes it hard to imagine a better version existing in some vault.

I played it recently for a friend who mostly knows rock through playlists and algorithmic blends. We were in a kitchen with too many windows and a chipped floor, and the opening bars turned the space into a commons. People who had drifted in and out of conversation started tapping on the table. Someone snapped. Someone laughed at nothing in particular. “C’mon Everybody” doesn’t require fidelity upgrades to bloom, but through modern studio headphones you catch the pleasing grit: the edges of the consonants, the tightness of the echo, the slightly compressed grit that feels like lacquer on a well-worn instrument.

Here’s a thing every young band could learn: insist on clarity of purpose. The record never tries to be more than what it promises, yet it also never settles for less. It is an invitation, yes, but it’s also instruction—how to build a party out of air and time, how to pace a shout so it doesn’t become a scream. Its energy is not a tidal wave; it’s a metronome with swagger.

“C’mon Everybody is that rare two-minute engine: it doesn’t just move; it teaches you how to move with it.”

When I was a teenager discovering fifties rock, I assumed the appeal was mostly historical. Then I heard this track in a secondhand shop on a rain-glossed afternoon, and history gave way to vibration. The clerk had stacked old 45s near the register, and the single hit like a polite alarm. Two customers started nodding in sync; the room brightened by a few degrees. There is a reason this cut survives in cover versions, in TV snippets, in jukebox fantasies: it behaves like a reliable fuse.

Rock and roll can be ornate; it can be orchestral; it can build cathedrals of sound. Cochran chooses a garage. That contrast—glamour outside, grit inside—makes the track paradoxically elegant. The vocal is polished enough to sell, rough enough to convince. The lead interjections flash without grandstanding. The rhythm breathes, leaving little pockets of air you can dance in. The confidence is unmistakable, but it’s communal rather than soloistic: not “look at me,” but “join me.”

Critically, the song also works in the quiet. Try it at low volume late at night. The foot-taps shrink, the room tightens, and the vocal becomes conspiratorial. Suddenly the record isn’t a party; it’s a plan. The promise—come over, we’ll make something happen—still thrills because it feels like a shortcut past hesitation. If you’re a player yourself, the arrangement’s compactness is instructive; it’s tempting to over-decorate, but restraint gives excitement a surface to spark against. No wonder so many aspiring players look to material like this when starting out; it’s a masterclass in directness you can absorb faster than any formal guitar lessons.

From a historical vantage point, “C’mon Everybody” arrives in the hinge years when rockabilly’s country-blues DNA was being repackaged for mass teenage audiences. Cochran isn’t a preacher or a wildman in this performance; he’s a translator. He filters the idiom through a suburban lens without sanding it dull. Even the brief instrumental break models the aesthetic: articulate, catchy, recession-proof against time.

I’ve been careful to avoid mythologizing details that can’t be verified, because this era invites tall tales. What we can say with confidence is that Liberty Records issued the single in 1958, that Cochran co-wrote it with Capehart, and that the track made a significant splash in the U.K. while carving a respectable stateside presence. We can also say the record’s afterlife has been loud: covers, syncs, continual rediscovery by listeners who stumble on that title and realize it’s more than a slogan—it’s a structural principle.

One more vignette: a road trip with a cracked dashboard and a stubborn radio. Somewhere outside the city, the scan lands on an oldies set, and there it is—those opening bars like an open gate. The car speeds up without anyone touching the pedal. The sky is ordinary, traffic is ordinary, but the air in the cabin lifts. For three minutes the map looks simpler. A song can do that when the architecture is honest.

It’s tempting to frame the track as “just” a party cut. But the word “just” doesn’t fit. There is intent in the compression, elegance in the repetition, a craftsman’s pride in the way the performance turns space into momentum. You can turn the volume down and focus on the mechanics; you can turn it up and stop thinking entirely. The switch toggles effortlessly because the design welcomes either mode.

For the archivists among us, the lineage is also notable. Cochran’s influence bled into British beat groups, who prized the briskness and the youth-coded invitation. Later punk scenes would recognize the efficiency too—short, sharp, decisive. Yet “C’mon Everybody” never sounds stern or doctrinaire; the smile is built into the groove. It’s a welcome that arrives already halfway to the door.

One listening trick I recommend: cue the track on a system with unglamorous speakers, then again on a clean setup so you can hear the attack, the reverb tail, the way the room folds around the snare. The record’s charm survives either way, but the second pass reveals little production choices that reward attention. For deep night sessions, resist the urge to over-process or upmix; leave the mono intact. The centerline focus is part of its locomotion.

I also like to imagine the young Eddie Cochran assessing the take, hearing not only crowd appeal but a self-portrait: energetic, neat, persuasive. The song doesn’t stretch his range or beg for ornament. It captures him as a leader of ceremonies who knows the value of brevity. Sometimes you earn longevity by using less time.

If “C’mon Everybody” is new to you, start with the original single. Then explore its neighbors in Cochran’s catalog to hear how he balanced tenderness and bravado elsewhere. But don’t skip the simple pleasure of replaying this exact side immediately after it ends. The outro lands like a door closing softly. The quiet afterward feels like a street after the parade: confetti in the gutter, a promise lingering.

In the end, the track is not merely an artifact of the fifties; it’s a living, renewable invitation. It needs no period costume to function. Played today, it still finds the soft spot between planning and action, between the thought and the move. And that is why it endures.

Before I wrap, a small note for collectors: some reissues boast improved transfers; if you’re choosy about editions, the better ones present a touch more air without sacrificing punch. The difference isn’t essential, but it’s pleasant, like cleaning a window you didn’t realize was dusty. If you explore those versions, you may catch details that were always there—tiny shifts in breath, the faintest resonance after a strike—that help the performance stand up to modern premium audio habits built around clarity and immediacy.

All this from a single that barely cracks three minutes. That’s the trick. The party ends before the neighbors call. The promise remains.

By the time the last chorus fades, you’re either in or you aren’t. I suspect you will be. Press play again, let the night redraw itself, and see how ordinary rooms turn elastic.

Listening Recommendations

-

Buddy Holly – “Rave On”

A compact, buoyant charge from the same era; similar economy, with a buoyant vocal that snaps listeners to attention. -

Gene Vincent – “Be-Bop-A-Lula”

Sultry rockabilly glide; leans on feel and swagger the way Cochran’s single leans on forward motion. -

Chuck Berry – “Sweet Little Sixteen”

Rhythm-first propulsion and observational lyrics; maps a teenage world with quick brushstrokes. -

Jerry Lee Lewis – “Great Balls of Fire”

Boiling energy and percussive keys; a parallel lesson in how minimal components can feel huge. -

Little Richard – “Keep A-Knockin’”

Relentless drive and shouted charisma; the ecstatic end of the same dance-floor spectrum. -

The Everly Brothers – “Wake Up Little Susie”

Tighter harmonies and sly narrative; shows how innocence and mischief can share a single, unforgettable hook.