The air in July of 1958 was thick. It hung heavy over manicured lawns and clung to the chrome of parked Chevrolets. From the open windows of suburban homes, the radio offered a steady diet of sanitized pop and lovelorn crooners. But then, something else tore through the static—a sound that was lean, restless, and utterly unapologetic.

It began not with a bang, but with a thud. A percussive, almost primal pulse laid down by a stomping acoustic guitar and insistent handclaps. Then came the riff. A gritty, muscular, and impossibly catchy phrase from an electric guitar, circling like a shark in shallow water. This was the sound of a problem, a grievance, a kid who had finally had enough. This was the sound of Eddie Cochran’s “Summertime Blues.”

Released as the B-side to the far more conventional ballad “Love Again,” the track was an accident that became a manifesto. It never anchored a proper studio album during Cochran’s lifetime, a testament to the single-driven market of the era. But in its two minutes of raw, coiled energy, it articulated a feeling that an entire generation was just beginning to understand: the profound, maddening powerlessness of being young.

Cochran, working with his manager and co-writer Jerry Capehart, crafted this concise piece of music at Gold Star Studios in Hollywood, a space that would become legendary. Yet the recording feels less like a studio creation and more like a field recording from the suburbs. You can almost feel the linoleum floors and the humid night air. The production is brilliantly spare. Earl Palmer’s drums are a steady, driving heartbeat, while Connie “Guybo” Smith’s bass provides a simple, foundational thump.

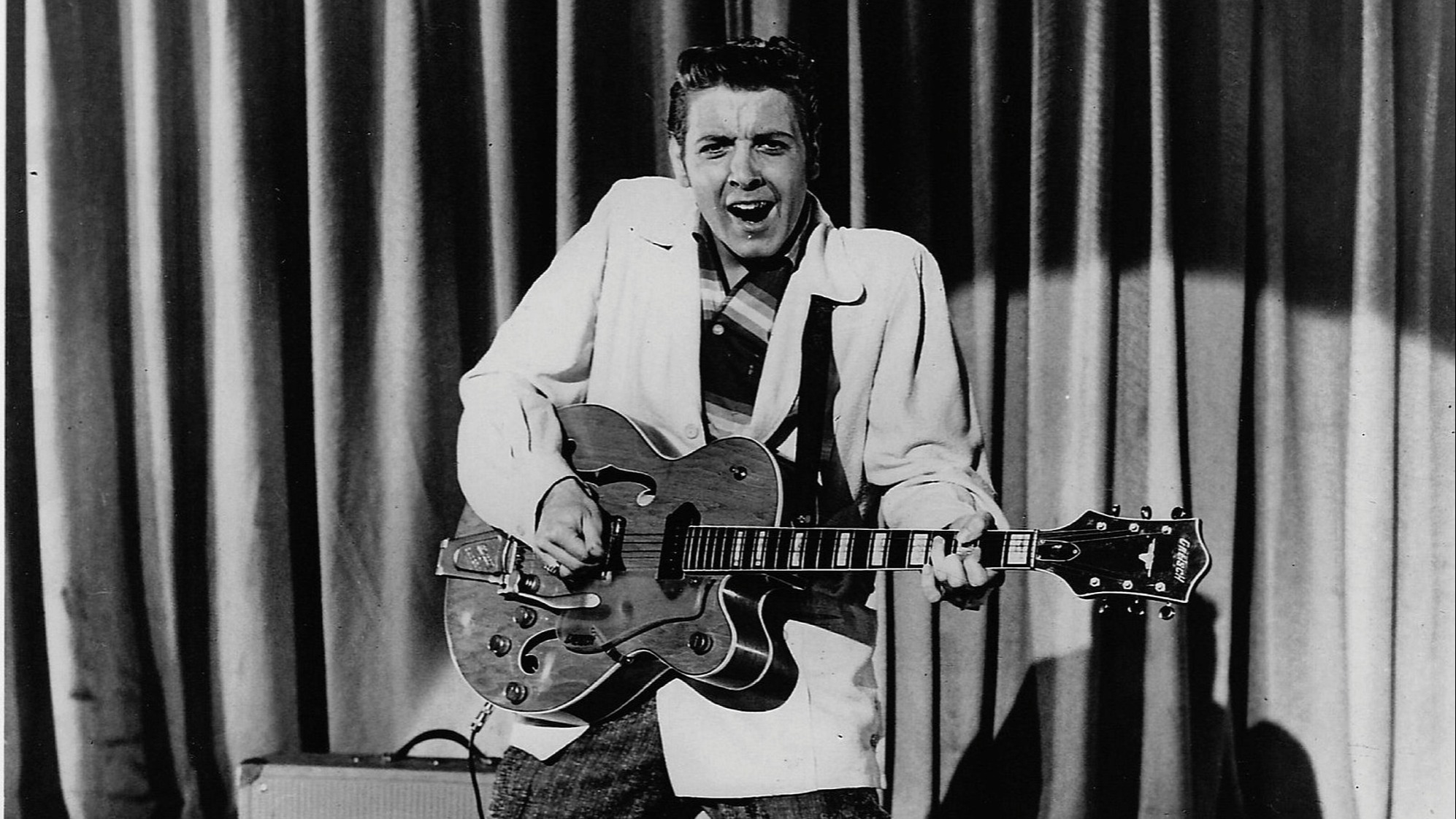

There is no artifice here. Unlike the boogie-woogie hits of his contemporaries, there is no rollicking piano to soften the edges or a saxophone to sweeten the melody. It’s all about the guitar and the voice. Cochran, a prodigious talent, overdubbed all the guitar parts himself. His Gretsch 6120 guitar sounds less like an instrument and more like a coiled spring, its tone sharp and resonant, cutting through the mix with purpose. The acoustic rhythm guitar is pure propulsion, a relentless chugging that dares you to sit still.

“The track is a conversation between a kid and a world that won’t listen, and fifty years later, the line is still busy.”

But the true genius lies in the vocal arrangement. Cochran doesn’t just sing the song; he performs it as a one-act play. He is the exasperated teenager, his voice full of youthful twang and simmering frustration. And then, in a feat of primitive studio wizardry, he becomes the voice of authority—a deep, booming, dismissive baritone that echoes as if from on high. “I’d like to help you son, but you’re too young to vote.” It’s a theatrical trick that transforms the song from a simple complaint into a multi-layered dialogue of dissent.

The lyrics are a masterwork of economy, laying out the teenager’s dilemma in three perfect, inescapable verses. First, there’s the economic trap: “I’m a-gonna raise a fuss, I’m a-gonna raise a holler / About a-workin’ all summer just to try to earn a dollar.” It’s the universal plight of the dead-end summer job, where the effort never seems to match the reward. The frustration is palpable, a feeling that resonates as strongly in a gig-economy landscape as it did in the post-war boom.

Then, Cochran pivots to the political. The protagonist tries to appeal to a higher power, his congressman, only to be shut down by the very system meant to represent him. It was a startlingly direct piece of social commentary for 1958, a time when teenage music was supposed to be about cars and sock hops. Cochran wasn’t just singing about a bad mood; he was singing about disenfranchisement.

Finally, the conflict comes home, to the family. The desire for freedom—a night out, the keys to the car—is met with parental authority. The call-and-response with the deep-voiced “boss” (a stand-in for his father, his employer, the government) is the song’s knockout punch. Every request is denied, every avenue is blocked. The only possible response is the song’s central, helpless refrain: “Sometimes I wonder what I’m a-gonna do / But there ain’t no cure for the summertime blues.”

That raw, coiled energy has sent countless kids to their rooms, not in punishment, but in a determined search for online guitar lessons, hoping to unlock that same power of expression. Played on a high-fidelity home audio system, the track reveals its subtle textures: the woody thwack of the acoustic against the electric grit, the cavernous echo on the boss’s voice, the organic unity of the handclaps. It is a recording that feels alive.

Decades after its release, “Summertime Blues” remains a foundational text. The Who amplified its aggression into a thundering hard-rock anthem. Blue Cheer twisted it into a sludgy, psychedelic roar. Its DNA is present in punk rock’s rebellion, in grunge’s angst, and in any song that dares to speak truth to power from a kid’s point of view.

It is more than a nostalgic artifact. It is a perfectly constructed expression of a timeless human condition. It’s the feeling of wanting a voice but having no vote, of having desires but no agency, of seeing the world move on without you. It’s the heat, the boredom, and the righteous indignation of youth, distilled into two minutes of pure, uncut rock and roll. To listen to it again is to be reminded that some problems don’t need a cure, they need an anthem.

Listening Recommendations

- Gene Vincent & His Blue Caps – “Be-Bop-A-Lula”: Captures a similar brand of smoldering, minimalist cool with an equally iconic vocal performance.

- The Who – “My Generation”: Takes the teenage frustration of “Summertime Blues” and injects it with explosive, stuttering rage.

- Johnny Burnette and the Rock ‘n Roll Trio – “Train Kept A-Rollin'”: For another blast of raw, overdriven guitar that predated and influenced the British Invasion.

- Link Wray & His Ray Men – “Rumble”: An instrumental that speaks volumes, channeling a similar mood of rebellious tension through pure guitar swagger.

- Vince Taylor & His Playboys – “Brand New Cadillac”: A slice of frantic British rockabilly that matches Cochran’s energy and sense of wild abandon.

- The Sonics – “Have Love, Will Travel”: A garage-rock explosion from the next generation, proving the raw, stripped-down sound never went out of style.