The first time I really heard it—not just as background noise in a dim cafe, but truly heard it—I was sitting alone in a cheap, rented room in a strange city. It was one of those cold, dead-of-winter nights where the silence is so heavy it feels like a physical blanket. The radio, tuned to an oldies station perpetually stuck at the perfect moment between two eras, was my only company.

And then the strings started.

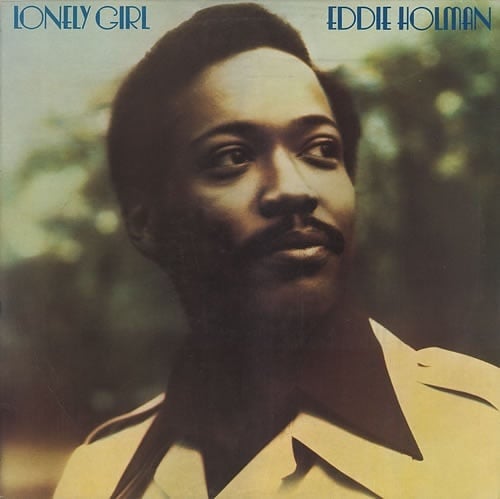

They didn’t crash in; they just began to bloom, like a slow-motion cinematic swell pushing the listener forward into an inevitable emotional reckoning. It was Eddie Holman’s “Hey There Lonely Girl,” and in that moment, in that quiet room, it ceased being a golden-era soul track and became an architectural marvel of feeling.

The song, released in late 1969 on the ABC label, was a pivotal moment in Holman’s fascinating, diverse career, though it built on an earlier tune. The original 1963 version, “Hey There Lonely Boy,” was a modest hit for Ruby and the Romantics. Holman’s rendition, which flipped the gender, took the core melodic genius of Leon Carr and Earl S. Shuman’s composition and dressed it in the most luxurious, heartbreaking sonic tapestry the end of the decade could muster. It wasn’t just a cover; it was a transmutation.

The Philadelphia Sound’s Quiet Beginning

While many associate the term “Philadelphia Soul” with the sophisticated, driving grooves of the early to mid-1970s—the Sound of Philadelphia (TSOP) machine engineered by Gamble and Huff—Holman’s recording is a vital precursor. It was recorded at Virtue Studios in Philadelphia, and the production, credited to Peter De Angelis, has the polish and emotional breadth that would soon define the city’s sound, but with an intimacy that precedes the slicker disco-adjacent sheen.

The initial texture is built on a simple foundation: a steady, almost march-like drum beat with brushes, and a bass line that walks with a beautiful, understated dignity. The rhythm section never rushes, establishing a deliberate, mournful tempo. Over this framework, a soft, arpeggiated figure from a piano traces the core harmonies, providing a subtle, twinkling anchor. It’s the sound of a man watching a stranger from across a crowded room, building up the courage to speak.

The orchestration, however, is the real star. It is an arrangement built for tears, not for dancing. Sweeping violin lines enter at the perfect emotional apex, not just following the melody but commenting on the singer’s anguish. Cellos and violas provide a rich, deep cushion underneath Holman’s voice, a warmth that is both comforting and tragically ironic given the song’s theme of isolation.

“The orchestration on ‘Hey There Lonely Girl’ is an arrangement built for tears, not for dancing.”

The guitar, often relegated to a quick, clean strum or a muted, funky rhythm in contemporary soul, is used here for sparse, carefully placed decorative touches. A gentle, high-register electric guitar lick surfaces only occasionally, a faint shaft of light that cuts through the surrounding gloom before receding again into the sonic fog. It is an exercise in restraint—every instrument waiting its turn to serve the narrative.

The Voice: A Stratosphere of Vulnerability

But you cannot talk about this piece of music without talking about the voice. Eddie Holman’s vocal performance is nothing short of breathtaking. His range is famously high, a pure, ringing falsetto that sails into the stratosphere without ever cracking or sounding thin. The key to the song’s enduring power is not just the height of his register, but the immense emotional weight he carries with it.

Holman’s delivery is disconsolate, yet overwhelmingly compassionate. He is singing directly to the “lonely girl” across the way, a stranger whose sadness he perceives and mirrors. His voice quivers with a shared, sympathetic vulnerability, especially as he hits the sustained, upper-register notes on the word “lonely” in the chorus. It is not a detached spectacle of vocal athleticism, but a direct line to the listener’s own reserves of heartache.

This masterful control of timbre and dynamic—the way he pulls back to a whisper only to soar into a cathartic plea—transforms a simple ballad structure into high drama. The reverb on his vocal is generous but tastefully applied, giving his voice a halo of space, a sense of being both intimately close and impossibly distant, floating above the heavy strings and soft drum pulse.

Context and Legacy: A Career Arc Defined by Contrast

Holman’s earlier work, such as the 1966 hit “This Can’t Be True,” already showcased his vocal brilliance, but “Hey There Lonely Girl” cemented his place in soul history. Released as a single, it eventually became the defining track of his 1969 album, I Love You. It’s a remarkable cornerstone of his legacy, peaking near the top of the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 chart in early 1970 and finding huge success later on the UK Singles Chart, demonstrating its timeless appeal.

The longevity of this song is no accident. It taps into a universally understood feeling: the ache of seeing someone else’s profound sadness and recognizing your own reflection in it. It’s the soundtrack to every lonely, late-night drive where the headlights cut through the rain and the dashboard clock reads a time no one should be awake.

I think of a college friend who used to listen to this on repeat while studying late, using the song’s contained sorrow as a kind of emotional focus. Its melancholy provided an unexpected comfort, proving that the best sad songs don’t deepen your despair; they simply acknowledge it. For those of us who appreciate the subtle details in musical performance, investing in something like premium audio equipment can unlock the nuanced layering of the strings and the clarity of Holman’s formidable vocal control. It’s a track that rewards deep, focused listening.

Holman’s talent was multifaceted, stretching from R&B to gospel later in his career, but this ballad, this empathetic snapshot of connection across a chasm of solitude, remains his signature. It is a moment of pure, cinematic soul glamour juxtaposed against the grit of a genuinely felt, universal human emotion.

The power of this piece of music is its narrative economy. In three minutes, it moves from observation to heartfelt connection to the quiet, open-ended promise of future solidarity. It is a stunning display of production, vocal mastery, and melodic purity, and it deserves to be listened to not as an oldie, but as a living, breathing testament to the enduring power of classic soul.

Listening Recommendations

- The Delfonics – “La-La (Means I Love You)” (1968): Shares the lush, sweet Philadelphia string arrangement and emotional directness.

- The Stylistics – “Betcha by Golly, Wow” (1972): Another example of soaring falsetto lead over a deeply romantic, orchestrated backdrop.

- Jerry Butler – “Only the Strong Survive” (1969): Features a similarly rich, soul-orchestral arrangement, capturing the drama of late-60s Chicago/Philly soul.

- Ruby and the Romantics – “Hey There Lonely Boy” (1963): The original version, providing an interesting contrast in vocal style and arrangement approach.

- Percy Sledge – “When a Man Loves a Woman” (1966): Possesses the same kind of deep, heartfelt sincerity and gradual, emotional build via orchestration.

- Gene Chandler – “Duke of Earl” (1962): Demonstrates another iconic use of the high-register male vocal with a classic R&B arrangement that focuses heavily on narrative.