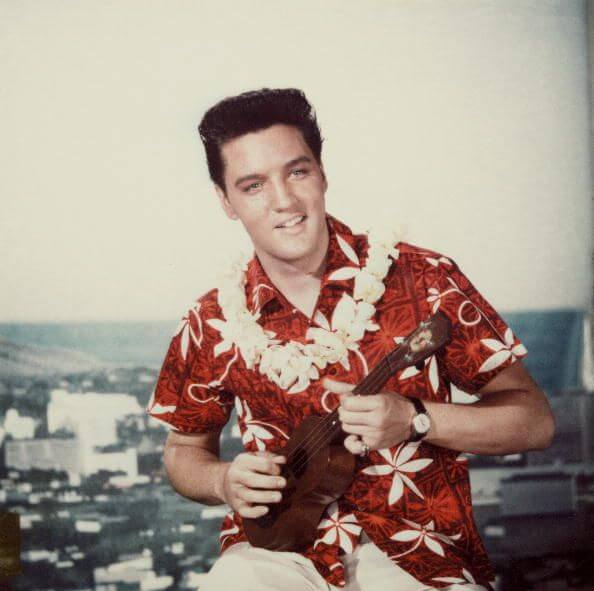

The year 1973 did not begin with a quiet sunrise; it arrived with a flash, the digital ghost of a spectacle beamed across a world that was still reeling from its own decade of seismic shifts. For those of us who remember gathering around the television, the image of Elvis Presley, dazzling in a white jumpsuit embroidered with the American eagle, performing live in Honolulu, felt less like a concert and more like a coronation, an acknowledgment of a history that could not be denied.

The resulting record, Aloha from Hawaii via Satellite, is an artifact of pure cultural saturation. Nestled within this landmark live album, right after the dramatic sweep of “An American Trilogy,” is a five-minute-long piece of music that functions as a devastating, self-penned epitaph: “My Way.”

This wasn’t a studio retake, nor a casual concert staple; it was the King of Rock and Roll, in the twilight of his reign, taking on Frank Sinatra’s signature anthem, stripping away the elder crooner’s cool detachment, and injecting it with a raw, almost desperate sincerity. It’s the sound of a man confronting his legend, his successes, his failures, and the narrow, difficult path that brought him to this brightly lit stage in the middle of the Pacific.

The Sound of a Reckoning

Producer Felton Jarvis and the Joe Guercio Orchestra, which served as Elvis’s central musical pillar in this era, understood the necessity of grandeur. They constructed an arrangement that was less a background and more a sonic canvas worthy of a historical moment. The track begins not with a bang, but with a hushed, reverent entry: the mournful, stately chords of a grand piano, immediately setting a tone of deep, personal reflection. This is quickly augmented by the brass section—not the frantic horns of a Memphis session, but measured, velvet tones that hint at a coming storm.

The texture of the sound here is massive, yet surprisingly intimate. We hear the echo of the International Center in Honolulu, but Elvis’s voice is placed right in the foreground, mic’d close, capturing every subtle catch and tremor. When he begins, “And now, the end is near…” the vibrato is less a vocal ornament and more a manifestation of the song’s inherent tension.

The instrumentation builds like a classical symphony approaching its climax. The rhythm section—drums and bass—maintains a restrained, almost funereal pace, a steady heartbeat beneath the swelling emotion. James Burton’s guitar work, usually so fiery and distinctive in Elvis’s band, is remarkably sparse, limited mostly to a few elegant, soaring counter-melodies that fill the space between verses. He provides color, not flash, acknowledging the song’s operatic scale.

It is the string section that carries the lion’s share of the emotional weight. They rise and fall with the drama of the lyric, not simply echoing the melody, but underscoring the melancholy of Paul Anka’s adapted words. It is this orchestral sweep, a hallmark of Elvis’s Vegas-era sound, that lifts the song from a simple pop cover into a towering, career-defining performance. For anyone seeking to analyze the orchestral pop arrangements of the 1970s, or even aspiring composers looking at sheet music from the era, this recording is a masterclass in controlled, powerful melodrama.

Contrast: The Man vs. The Myth

The power of Elvis’s “My Way” lies in its profound, almost accidental, contrast with the singer’s public persona. Frank Sinatra’s earlier, definitive version spoke of accomplishment, the proud assertion of a man who had conquered the world. When Elvis sings it, the words take on a tragic ambiguity. The lyrics about “taking all the blows” and “standing tall” are delivered not with Sinatra’s defiant snarl, but with a weary, almost pleading conviction.

The performance becomes a micro-narrative in itself, a three-act play unfolding over four minutes. In the first verse, the vocal is cautious, almost resigned. Then, as he hits the middle section—“I’ve loved, I’ve laughed and cried, I’ve had my fill, my share of losing…”—a palpable shift occurs. He starts to talk-sing, the professionalism of the show dissolving for a moment, letting the real-life struggles bleed into the lyric. It’s a gut-wrenching moment of artistic honesty.

The final chorus, of course, is pure catharsis. The dynamics are maxed out, the orchestra a wall of sound, and Elvis’s voice is an overwhelming, glorious roar. The famous final lines: “The record shows I took the blows, and did it my way!” are not a boast; they are a necessary, life-affirming scream against the gathering darkness. This is not a song about how he lived, but the desperate, all-consuming need to justify the choices he made.

“This performance, shimmering under the Hawaiian lights, is less a cover and more a confessional, the final, operatic statement of a complicated life.”

For the dedicated enthusiast setting up their home audio system, this track is a perfect test. The separation of the soaring strings, the crisp percussion, and the deep resonance of Elvis’s baritone offer a rich, complex audio experience. It’s a testament to the live recording quality of the era that such a dramatic dynamic range was captured.

The impact of this live rendition, released originally on the Aloha from Hawaii album, grew exponentially after Elvis’s death in 1977, when a version from the TV special Elvis in Concert (also produced by Felton Jarvis) became a posthumous single. It was cemented as his parting statement, the final word from the King. It remains one of the most powerful, and sadly prescient, vocal performances of the twentieth century. It’s a piece of music to be listened to in solitude, with the lights low, and the full weight of his story in mind.

Listening Recommendations (Adjacent Mood/Era/Arrangement)

- Elvis Presley – An American Trilogy (1972): Shares the same core Aloha from Hawaii setting and the same theatrical, orchestral grandeur.

- Tom Jones – She’s a Lady (1971): A comparable display of 70s vocal power and brass-heavy, polished Vegas-style arrangement.

- Frank Sinatra – It Was a Very Good Year (1966): Offers the same deep, melancholy self-reflection on a life fully lived, backed by rich strings.

- Scott Walker – Jackie (1967): Explores a similar mood of cinematic, almost overwrought European chanson filtered through a pop vocalist’s sensibility.

- Shirley Bassey – Diamonds Are Forever (1971): Features a powerhouse vocal performance over an utterly dramatic, lushly recorded orchestral backdrop.

- Glen Campbell – Wichita Lineman (1968): A masterful piece of sophisticated pop-country arrangement, showcasing another singer facing a quiet, personal loneliness.