To hear Emmylou Harris sing is to encounter something both ancient and fragile—a voice that seems to drift in from another room, carrying memories you didn’t know were yours. For decades, she has been crowned the “Queen of Americana,” a title that barely captures her influence on folk, country, and roots music. Yet behind the reverence, the Grammys, and the halo of harmony vocals lies a far more complex truth: Emmylou Harris built her legacy by living two lives at once, and for more than thirty years, the cost of that duality remained largely invisible.

This is not a story of scandal or deception. It is a story of devotion—of what happens when an artist commits herself so fully to music that there is little left over for anything else.

The Architecture of Solitude

Emmylou Harris’s life reads less like a traditional rise-to-fame narrative and more like a slow, deliberate shedding of certainties. Born in 1947 into a military family, Harris grew up in a world governed by discipline, restraint, and emotional understatement. Her father, a Marine Corps officer, survived years as a prisoner of war in Korea. In that household, resilience was not encouraged—it was expected.

Music became her refuge long before it became her profession. It was the one space where vulnerability was permitted, where emotion could breathe without explanation. That instinct—to internalize pain and translate it into sound—would later define both her art and her personal life.

When Harris abandoned her early ambitions in drama and found herself drawn to the folk revival of Greenwich Village, she wasn’t chasing fame. She was searching for a vocabulary. Songs offered what ordinary language could not: a way to articulate longing without demanding resolution.

Early Losses and Unspoken Goodbyes

Her debut album, Gliding Bird (1969), arrived quietly and disappeared just as fast. Commercially overlooked, it coincided with the collapse of her first marriage to songwriter Tom Slocum. What followed was one of the most painful chapters of her life—one she rarely speaks about in detail.

As a young, struggling musician and single mother, Harris made a decision that would haunt her for years: she sent her daughter, Hallie, to live with her grandparents so she could pursue music in Washington, D.C. It was not abandonment, but it felt like betrayal. That ache—of choosing art over proximity, vocation over domestic stability—would become a recurring undertone in her voice.

From that point forward, Harris lived in a state of emotional partition. Onstage, she was luminous and assured. Offstage, she was learning how to survive with absence.

Gram Parsons and the Birth of a Myth

Everything changed when Emmylou Harris met Gram Parsons.

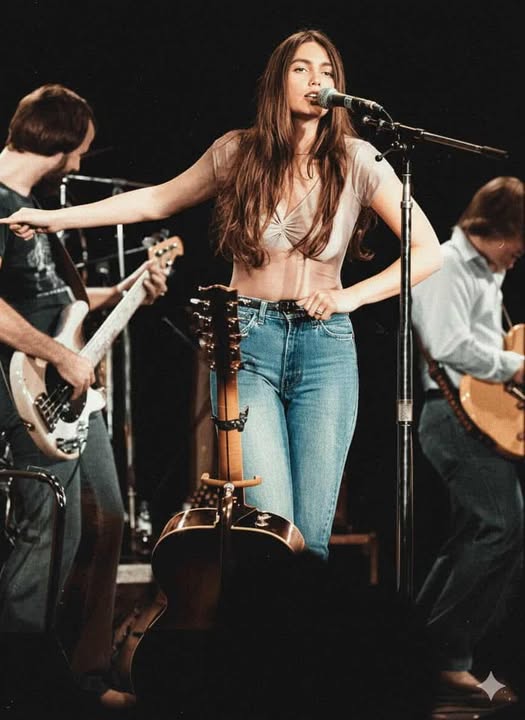

Their partnership was brief but seismic. Together, they reimagined country rock not as nostalgia, but as something aching, reverent, and dangerously alive. Their voices intertwined with uncanny intimacy, as if neither could fully exist without the other.

But Parsons was also volatile, self-destructive, and orbiting disaster. When he died in 1973, Harris lost not just a collaborator, but the one person who had seen her completely—artist to artist, without compromise.

Instead of retreating, she transformed grief into momentum. Pieces of the Sky (1975) and the devastating “Boulder to Birmingham” did more than establish her solo career; they announced her emotional truth to the world. From that moment on, a pattern emerged: Harris’s most transcendent work often rose directly from personal devastation.

Love, Marriage, and the Machinery of Success

In the years that followed, Harris married twice more—producer Brian Ahern and songwriter Paul Kennerly. Both relationships began in creative communion and ended under the weight of touring schedules, studio demands, and the relentless expectations of success.

Harris once described herself as “a really good ex-wife.” It was a line delivered with humor, but beneath it lay a hard truth. She was loyal to the music in a way that left little room for permanence elsewhere. Where others built homes, Harris built catalogs. Where others rooted themselves, she stayed in motion.

This was the second life she lived—the private life shaped by sacrifice, compromise, and a long acceptance that her deepest commitment could never be divided evenly.

The Power of Trio and Artistic Liberation

In 1987, Harris found a different model of connection with Dolly Parton and Linda Ronstadt. Trio was not just a commercial triumph; it was a cultural statement. Three women, each with formidable careers, stood shoulder to shoulder and proved that collaboration—not competition—could redefine industry expectations.

The success of Trio gave Harris the freedom to explore less conventional terrain. Albums like Wrecking Ball (1995) stripped away polish in favor of atmosphere and emotional abrasion. Red Dirt Girl (2000) turned inward, offering a raw reckoning with memory, place, and regret.

These records felt like liberation—not from pain, but from the need to disguise it.

A Life Reclaimed on Her Own Terms

Today, Emmylou Harris lives outside the traditional narratives once used to measure success. She is not defined by marriage or domestic legacy, but by purpose. Through activism, advocacy, and her animal rescue organization, Bonaparte’s Retreat, she has built a life grounded in care rather than compromise.

She stands as proof that fulfillment does not require conformity. That meaning can be constructed quietly. That love can exist in many forms—songs, causes, communities—without diminishing its power.

Emmylou Harris remains the silver thread running through Americana music: subtle, unbreakable, and true. Her voice carries weight because it has lived the consequences of its choices. And in every note, you can hear the price she paid—not with bitterness, but with grace.