There are songs that entertain, songs that climb charts, and then there are songs that linger like dust in a sunset beam—quiet, golden, unforgettable. When Emmylou Harris recorded “Pancho & Lefty” for her 1979 album Blue Kentucky Girl, she wasn’t chasing a crossover hit. She was preserving a story. And in doing so, she gave one of Americana’s most poetic ballads a new and enduring life.

Originally written by the elusive troubadour Townes Van Zandt in 1972, “Pancho & Lefty” had already carried the dusty fingerprints of myth and melancholy. But in Harris’s hands, it became something softer and more spectral—less a campfire tale of outlaws and more a meditation on memory, loyalty, and survival.

While the song would later gain mainstream country success through Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard’s 1983 duet, Harris’s interpretation remains one of the most emotionally resonant versions ever recorded. It is less about swagger and more about sorrow. Less about legend, more about loss.

The Songwriter’s Shadow: Townes Van Zandt’s Original Vision

To understand Harris’s version, we must first step into the world of Townes Van Zandt. A songwriter revered by musicians and critics alike, Van Zandt was never a commercial powerhouse. Instead, he was a poet of the margins—a man whose lyrics cut deep and whose life mirrored the loneliness he so often wrote about.

Inspired, according to legend, by a television documentary on Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa, Van Zandt wove a fictional narrative of two outlaws: Pancho, the romanticized bandit who meets a violent end, and Lefty, the quiet companion who survives and retreats into anonymity in Ohio. The song unfolds like a faded photograph, offering glimpses rather than answers.

Was Lefty a traitor who sold out his friend? Or simply a man who chose survival over martyrdom? Van Zandt never spelled it out. The ambiguity is the magic. In just a few verses, he captures the complicated truth of human relationships: loyalty tested, dreams shattered, legends rewritten by time.

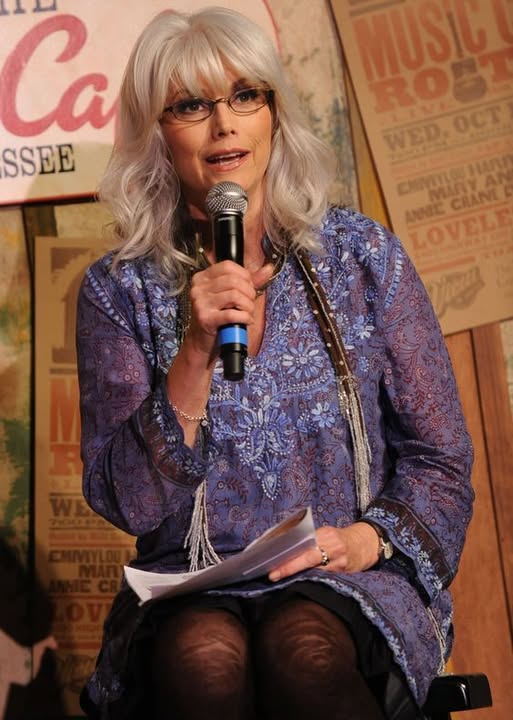

Emmylou Harris: The Interpreter of Souls

By the time Blue Kentucky Girl was released, Emmylou Harris had already established herself as one of country music’s most discerning interpreters of song. She possessed that rare gift: the ability to honor a songwriter’s intent while adding her own emotional fingerprint.

Blue Kentucky Girl would go on to reach No. 3 on the Billboard Top Country Albums chart and earn Harris a Grammy Award for Best Female Country Vocal Performance. The album marked a return to more traditional country sounds after a period of country-rock experimentation. Within that context, “Pancho & Lefty” fit perfectly—a story-driven ballad rooted in folk tradition.

Harris approaches the song not as an outlaw saga, but as a lament. Her voice—clear, almost fragile—floats over the arrangement with restrained sorrow. She does not dramatize Pancho’s death or Lefty’s exile. Instead, she sings as though recalling something half-remembered, something that still aches but no longer burns.

There is a quiet dignity in her delivery. Where other versions might emphasize the grit of the Old West, Harris leans into reflection. The result feels timeless. It could be about revolutionaries in Mexico—or about two friends who drifted apart in a small American town.

The Themes That Never Grow Old

At its heart, “Pancho & Lefty” is about what remains after the dust settles.

Pancho dies young, immortalized in song and myth. Lefty grows old, living in obscurity. The world forgets him. But he remembers. That contrast—between the glorified past and the lonely present—carries a sting that deepens with age.

For listeners who have lived a little, the song resonates in unexpected ways. Most of us have known a “Pancho”—someone charismatic, reckless, larger than life. And many of us, at one time or another, have felt like “Lefty”—the one who stays behind, who carries the memory while the legend grows elsewhere.

The genius of the song lies in its refusal to judge. There is no moral pronouncement, no tidy resolution. Life simply moves forward. Heroes fall. Survivors endure. Stories get told and retold, sometimes smoothing over the messy truths beneath them.

Harris understands this. She sings not with accusation, but with empathy. In her hands, Lefty is not a villain. He is human.

A Legacy Beyond the Charts

Though Harris’s version was not released as a major single, its inclusion on Blue Kentucky Girl helped cement the album’s critical and commercial success. Over the decades, her rendition has become a touchstone for fans who appreciate songwriting craft over spectacle.

When Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard later took the song to No. 1 on the country charts, it brought widespread attention to Van Zandt’s writing. Yet even amid that success, Harris’s earlier recording remains essential. It is the bridge between Van Zandt’s stark original and the polished duet that followed.

In many ways, Harris acted as a guardian of the song—keeping it alive in the late 1970s, introducing it to audiences who might not have encountered Van Zandt’s version. Her commitment to highlighting great songwriting, whether from Gram Parsons, Rodney Crowell, or Townes Van Zandt, has always been central to her artistry.

Why “Pancho & Lefty” Still Matters

Nearly half a century later, “Pancho & Lefty” endures because its themes are universal. Freedom versus security. Loyalty versus survival. Youthful glory versus aging anonymity.

The arrangement may be rooted in country-folk tradition, but the emotional landscape is vast. It speaks to friendships that changed, dreams that didn’t pan out, and the complicated grace of growing older.

Listening today, Harris’s voice feels like a companion on a long drive—steady, reflective, never intrusive. She invites you to consider your own Pachos and Leftys. To think about the roads taken, and those abandoned.

Some songs shout their message. Others whisper it across decades. “Pancho & Lefty,” in Emmylou Harris’s interpretation, does the latter. It is not merely about outlaws in Mexico. It is about all of us—our legends, our compromises, our memories.

And perhaps that is why it remains so powerful.

Because in the end, whether we are remembered as Pancho or fade quietly like Lefty, the story still matters. And thanks to Emmylou Harris, this one continues to be told—with grace, reverence, and a voice as clear as mountain air.