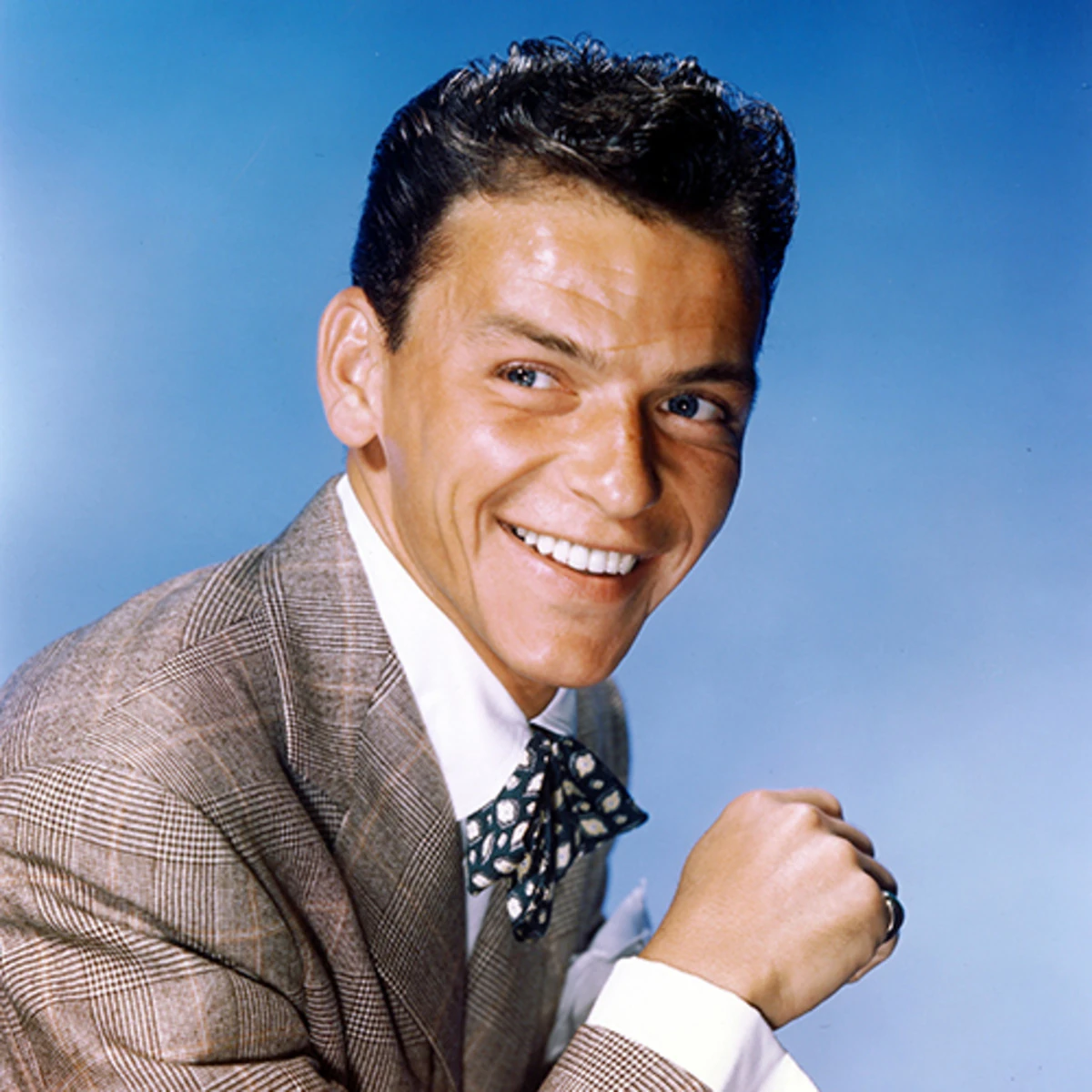

The air in the café was thick and still, the kind of late-November morning where the light is already failing by mid-afternoon. A silent snow was starting outside the window, blurring the edges of the city. I was nursing a lukewarm coffee, chasing a deadline, when the low, golden baritone drifted in from the vintage home audio system above the espresso machine. Not just any baritone, but two of them, in a stately, unhurried conversation. The sound was unmistakably that of Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby, and the piece of music was, inevitably, Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas.”

It is a curious thing, the cultural weight we put on a simple song—or, in this case, the union of two titans on a melody that already owned the holiday season. The history of “White Christmas” is, in many ways, the history of 20th-century American music, centered on Crosby’s iconic, multi-million-selling 1942 original (and the essential 1947 re-recording). Sinatra himself had multiple cracks at the tune across his career. But the version that resonates with such a specific, almost cinematic warmth is the one released on the album 12 Songs of Christmas in 1964.

This track is less a new interpretation and more a summit meeting—a moment where Ol’ Blue Eyes, then head of his burgeoning Reprise Records label, coaxed his musical idol and only real commercial rival, Bing Crosby, into the studio for a collaborative Christmas project. The album was produced by Sonny Burke and featured arrangements by Harry Simeone and Nelson Riddle. This specific recording of “White Christmas” is imbued with the spirit of that collaboration, capturing the respect and easy camaraderie between two legends who, for decades, had defined the very sound of American popular song.

The song arrives not in the stark, wistful manner of Crosby’s wartime original, but with a comfortable, mid-tempo orchestral swell. The arrangement here is not stripped-down or intimate; it’s a full, rich tapestry of mid-century studio craft. It leans heavily on the string section, with violins weaving a shimmering, nostalgic thread through the entire piece of music. The brass, particularly the subtle, warm French horns, fill out the lower registers, lending the track a stately, almost formal elegance.

Listen closely to the separation in the mix. Crosby takes the first verse, his voice a buttery, relaxed purr—the quintessential croon. It is a sound that defined an era, a natural, almost conversational delivery that revolutionized singing. His timbre is slightly darker, heavier with the weight of decades of association with this melody.

Sinatra steps in for the second verse, his voice brighter, his phrasing just a touch more elastic. There is an undercurrent of swing, even in this gentle ballad, a hallmark of his Capitol and Reprise eras. The contrast is not competitive, but complementary, like two master tailors presenting two different, equally exquisite cuts of the same luxurious material. They do not just sing the song; they inhabit their respective roles in its legacy.

The rhythmic backbone is subtle, kept firmly in the background so as not to overshadow the voices. The presence of the piano is mostly felt in the chordal scaffolding, a lush series of pads that support the central melody rather than driving it. The bass line is deep and acoustic, anchoring the arrangement with a gentle, walking motion that keeps the time flowing like a slow, perfect river. There is no major role for the guitar in this particular arrangement, the song instead relying on the sweeping power of the orchestra to convey its expansive holiday feeling.

This 1964 version carries the sonic signature of the era: wide stereo imaging, the vocals placed forward with a light, warm reverb, and a mastering job that prioritizes clarity and orchestral texture. It is a recording built for the kind of discerning listener who invested in premium audio equipment—the Hi-Fi enthusiast of the early 60s who wanted to hear every shimmering cymbal and the rich bloom of the cello section. It is a decidedly ‘Reprise’ sound, more polished and less rustic than many of Crosby’s earlier Decca recordings.

The emotional core of “White Christmas” has always been a gentle, deeply felt longing—for a bygone time, a distant place, or a perfect, idealized memory. Crosby, having sung it for the troops in the Pacific during the war, understood this longing profoundly. When the two men’s voices finally join together in the final refrain, it feels less like a performance and more like a shared, fond memory.

“The great magic of this recording is how it manages to feel both monumental and utterly casual, a fireside chat between two kings.”

It’s in this duet section that the real cultural moment crystallizes. We are hearing the two poles of mid-century American pop singing finally aligning. It is the handover of the crooning crown, performed with mutual respect and a genuine smile woven into the vibrato. It’s a moment that transcends the season, a lesson in vocal restraint and the power of shared experience.

This song, and indeed, this entire collaborative effort, serves as a poignant reminder that even the most enduring classics can be successfully revisited when the intentions—and the talent—are aligned. Whether one is learning the chords for the first time via sheet music or hearing the track drift from the radio on Christmas Eve, the sentiment remains pure, simple, and irresistibly nostalgic.

The enduring success of 12 Songs of Christmas—the rare collaboration that truly delivers—proves that some things are simply better together. It’s not just a holiday track; it’s a historical document, capturing two legends at a point of mutual admiration, reminding us that even the greats rely on one another to make a timeless sound.

Listening Recommendations

- Bing Crosby – “Silent Night” (1935): For the earlier, more pious, and historically significant side of Crosby’s foundational holiday catalog.

- Frank Sinatra – “The Christmas Song (Merry Christmas To You)” (1957): Features a similarly rich, Nelson Riddle-esque orchestral arrangement and Sinatra’s signature sophisticated phrasing.

- Nat King Cole – “The Christmas Song (Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire)” (1961): Shares the same warm, lush mid-tempo ballad feel and iconic crooning vocal quality.

- Perry Como – “It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas” (1951): Adjacent in mood and era, representing the same effortless, slightly formal pop style of the 1950s.

- Doris Day – “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” (1964): Offers a counterpoint of wartime yearning and orchestral swell, delivered with a similarly intimate vocal style.