The radio dial, circa 1959, was a contested landscape. Rock and Roll, still raw and unpredictable, wrestled with the smooth, professional balladry of the previous generation. Into this sonic battle, where the grit of Little Richard faced off against the polish of Perry Como, stepped a new kind of star: the teen idol. And perhaps no single piece of music better encapsulates the calculated, utterly charming sophistication of this new sound than Frankie Avalon’s “Venus.”

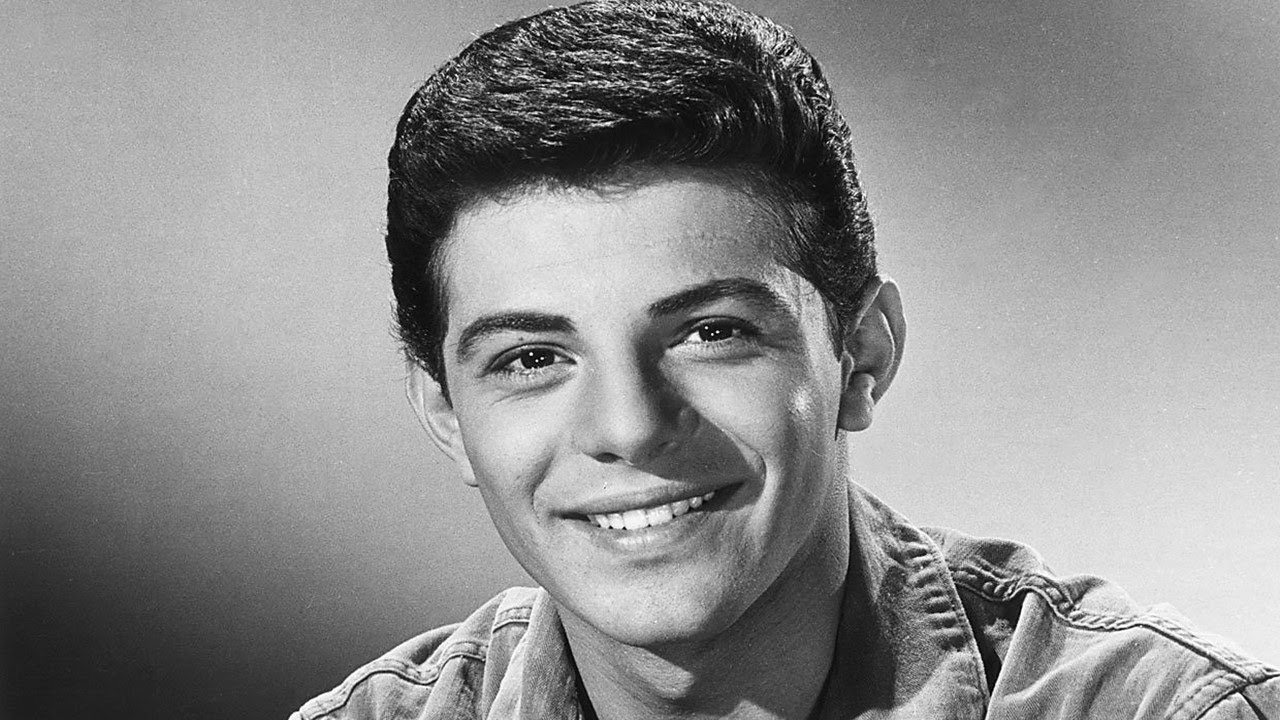

Close your eyes and picture the moment. It’s early 1959. The air is cold, but the hi-fi speaker radiates a soft, warm glow. Avalon—the fresh-faced Philadelphia trumpet prodigy turned singer—had already charted a few hits for Bob Marcucci’s Chancellor Records, establishing himself as a marquee name. But “Venus,” released as a single, was the defining moment. It wasn’t attached to a studio album initially; it was a focused strike on the pop charts, a move engineered to solidify his status not just as a hit-maker, but as the sincere, romantically yearning voice of a generation. When it soared to the top of the Billboard Hot 100 for five consecutive weeks, it confirmed the strategy: the teen market craved clean, orchestral romance.

The songwriting itself—credited to Ed Marshall, though some sources suggest a co-credit for Peter De Angelis—is a masterclass in direct, emotional simplicity. It’s a literal prayer, a plea to the Roman Goddess of Love to send a girl who will love him back. The lyrics are sweetly earnest, the kind of uncomplicated desire that felt utterly authentic to the young audience. But the genius of the record lies less in the words and more in the texture that Arranger Peter De Angelis layered around Avalon’s voice.

The Velvet and the Tremolo: Anatomy of an Arrangement

“Venus” is not a rock and roll song. It is a work of high-grade, studio-era orchestral pop masquerading as a teen anthem. The opening is immediate and dramatic. It starts not with the standard rhythm section, but with an echoing piano arpeggio, clean and sparkling, immediately establishing a soundscape that is both grand and intimate. This quickly dissolves into the song’s bedrock: a lush, almost overwhelming wash of strings.

The strings are the emotional core of the track. They swell and recede with cinematic purpose, utilizing a wide, luxurious vibrato. This isn’t background filler; this is front-and-center melodrama, pushing the listener toward the sublime. The dynamic shifts are subtle but effective. During the verses, the string section maintains a smooth, supportive flow, giving Avalon room to breathe. When the chorus hits, they soar, adding a cathartic lift to his plea.

Avalon’s vocal performance is remarkable for its restraint. His tone is light, possessing a natural tremolo that, in this context, sounds vulnerable rather than affected. He doesn’t belt; he sings into the microphone with an almost breathy urgency. Listen closely, and you can practically feel the close mic placement, giving his voice a warmth that contrasts perfectly with the cool, shimmering strings. It’s a delicate balance: the voice of the boy next door set against the scale of a Hollywood score. This meticulous engineering and mixing effort makes the original recording a crucial test of any serious premium audio setup.

Hidden beneath this velvet curtain are the rhythm players. The drums maintain a polite, nearly brushed rhythm, pushing a gentle backbeat that is felt more than heard. The bassline is subtle, a quiet anchor. The presence of a guitar is minimal, perhaps contributing to the overall gentle harmonic padding, but it avoids the choppy rhythm or sharp riffing that would define the emerging rock scene. This is a song about longing, and the band plays their part by not intruding on the vocal petition.

“It is a work of high-grade, studio-era orchestral pop masquerading as a teen anthem.”

The Teen Idol Archetype and a Cultural Shift

The success of “Venus” wasn’t just a musical triumph; it was a cultural one. It cemented the teen idol archetype that would dominate the pre-Beatles landscape. These were stars who were safe, romantic, and well-scrubbed, providing an antidote to the perceived dangers of artists like Elvis Presley or Jerry Lee Lewis. Avalon, along with peers like Bobby Rydell and Fabian, offered parents a palatable version of youth rebellion: controlled, charming, and focused on pure, innocent love.

For the aspiring musician, “Venus” was a gateway. It wasn’t technically complex, yet it felt sophisticated due to its arrangement. You can trace its impact through the sheer volume of sheet music sold, purchased by young pianists and singers eager to recreate its romantic sweep in their living rooms. It demonstrated how simple melodies could be elevated to majesty through the power of orchestration.

Frankie Avalon himself recognized the enduring power of the original recording, reportedly preferring it even to the disco re-recording he made in 1976. This first version, at just over two minutes, is concise perfection. It ends on a sustained high note—a final, soaring vocal plea accompanied by a huge, fading string chord—leaving the listener suspended in that moment of romantic aspiration. It’s a short journey, yet one that uses every second to maximize emotional impact. It is a definitive sonic photograph of 1959.

Today, listening to “Venus” is like opening a time capsule to a world where melodrama and sincerity were not mutually exclusive. It is a reminder that even in the ostensibly volatile early years of pop and rock, there was a deep, commercial hunger for beauty, polish, and uncomplicated romantic mythmaking. It holds up not just as a historical marker, but as an immaculately produced ballad whose heart-on-sleeve sincerity remains surprisingly resonant.

Suggested Listening

- “Mack the Knife” – Bobby Darin (1959): Shares a similar use of jazz-inflected, sweeping orchestral accompaniment defining the sophisticated pop of the era.

- “Put Your Head on My Shoulder” – Paul Anka (1959): Another massive teen idol ballad from the same year, using lush strings to deliver an intense, romantic vocal.

- “Only the Lonely” – Roy Orbison (1960): Features the same blend of dramatic strings and a passionate vocal performance, though Orbison leans into more operatic sorrow.

- “Teen Angel” – Mark Dinning (1959): Reflects the dramatic, cinematic storytelling and sentimental tone that defined many of the era’s biggest hits.

- “Where The Boys Are” – Connie Francis (1960): Captures the clean, polished, pop-friendly sound and subject matter of the beach/teen romance culture emerging at the decade’s close.