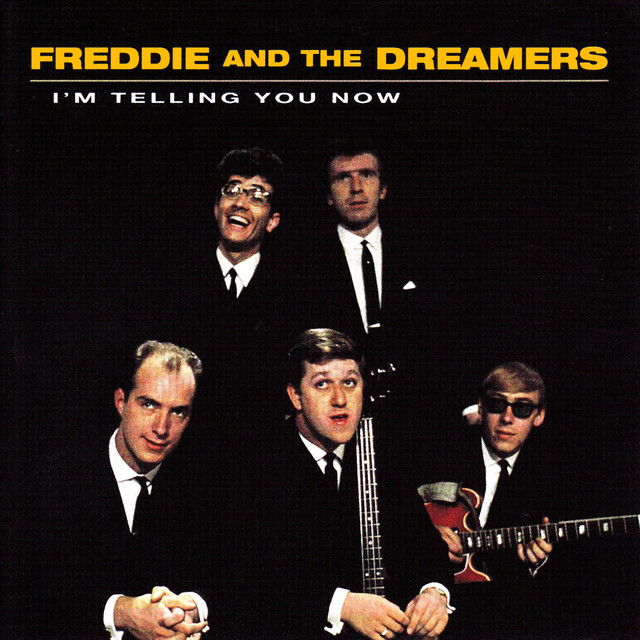

The early 1960s British Invasion, like a crowded carnival, had its rock titans—The Beatles and The Stones—whose influence would become canonical. But flanking the kings were the jesters, the side-show attractions whose charm lay in their sheer, unpretentious exuberance. Freddie Garrity, born on this day in 1936, was the ringleader of that auxiliary circus. He was the perpetual motion machine, the small, bespectacled man whose manic stage antics—the flailing arms, the frantic jump known simply as “The Freddie”—often overshadowed the simple, potent power of the music his band, The Dreamers, were creating.

To only remember the novelty of the performance is to miss the solid, melodic core of their output. This is why I return to a track like “Over You,” released as a single on the Columbia label in early 1964. It was their fourth single and, coming after a remarkable run of three UK Top 3 hits, its broad UK chart peak at number 13 might have been a small disappointment. Yet, this song, a non-album single at the time (though later compiled repeatedly), holds a deeper key to the band’s legacy than many of their higher-charting, zanier numbers. It’s the sound of the Dreamers stepping out of the spotlight and into a dim corner of the youth club dance floor, letting the heartbreak speak for itself.

The Sound of Manchester: Grit and Melodic Simplicity

Freddie & The Dreamers were Manchester beat, a slightly more rough-and-ready, less polished counterpart to the Merseybeat sound of Liverpool. Produced by John Burgess, who oversaw much of the band’s early career, “Over You” is an exemplar of their signature approach: brisk, rhythm-forward, and economical. There is no excess here, no indulgent studio trickery.

The foundation is built on an urgent, driving rhythm section of bass and drums, locked into a frantic two-beat feel that is both propelling and strangely mournful. Drummer Bernie Dwyer uses the ride cymbal with a sharp, almost breathless attack, creating an atmosphere of nervous energy that mirrors the song’s anxious subject matter. The rhythm guitar, likely played by Roy Crewdson, provides a persistent, chiming pulse, serving more as a textural element than a melodic one.

Then comes the lead guitar line. Derek Quinn’s fills are sharp, brief, and blues-inflected, cutting through the mix with a clean, slightly trebly tone that speaks of the close-mic’d, four-track limitations of the 1964 studio. There’s a wonderful moment in the break where a quick, high-register run by the guitar mirrors the rising emotional pitch of the lyric. It’s not flashy, but it’s precisely right.

The Missing Piano and the Naked Emotion

What strikes the listener immediately is the absence of any major keyboard presence. Unlike many of their contemporaries who used the piano or organ to flesh out the mid-range—think the classic Spector sound or even some of the more ornate Merseybeat arrangements—”Over You” relies almost entirely on the guitars, bass, and drums to carry the melodic and rhythmic weight. This stark arrangement strips the track bare. It feels intimate, almost aggressively direct.

Freddie Garrity’s vocal performance is central to the song’s success. His natural vocal timbre was high and thin, often lending itself to a playful or even frantic delivery. Here, however, that slight strain in his voice, his vibrato taut with emotion, perfectly conveys the narrator’s struggle. He is trying to convince himself he’s “Over You,” but the intensity of his plea betrays the lingering hurt. It’s a contrast between the joyous, cartwheeling public persona and the exposed, wounded heart.

This entire piece of music operates on a powerful contrast: the frantic, unrelenting rhythm section pushes forward, suggesting a desire to move on quickly, while Garrity’s voice drags slightly behind, anchored by the weight of the memory. It is a cinematic sound, the frantic footsteps of a man trying to outrun his own heartbreak.

Beyond the Gimmick: A Legacy of Craft

The commercial arc of Freddie & The Dreamers is often cited as a microcosm of the British Invasion’s rapid evolution and subsequent thinning of the herd. They were wildly successful early on, hitting the UK Top 3 multiple times. But by 1964, the British album scene was quickly moving towards complex songwriting and artistic control, exemplified by bands like The Kinks and The Beatles. The Dreamers, for a time, resisted this shift, choosing to remain rooted in simple, exuberant beat-pop—a choice that cemented their US success in 1965 (with the re-release of “I’m Telling You Now” hitting US #1), but saw their UK chart prominence fade quickly.

“The most authentic expression of early sixties heartbreak sounds like a sprint to forget a memory, not a melancholy ballad.”

“Over You” sits precisely on that historical cusp. It’s too polished and emotionally direct to be mere novelty, yet it retains the youthful energy and musical simplicity of the first-wave beat groups. It reminds me of the pure, unadulterated joy that could be found in a well-crafted three-minute pop song, before the pressure of complex orchestration and concept album work took hold. For today’s listener, exploring tracks like this on a music streaming subscription service is a vital way to understand the true diversity and depth of the 1964 pop landscape. It’s a testament to the skill of the band that their energetic simplicity, particularly the tight guitar work and propulsive rhythm, remains so compelling. They didn’t need the elaborate compositions of their peers; they simply needed to play with conviction.

I imagine a young Freddie, perhaps just a milkman before the fame, feeling this exact emotion. The feeling of being cornered by a memory you desperately want to shake off. This song is the sonic representation of that internal struggle. The sheer pace of the music is the only escape route he knows. In this context, the entire record becomes a vibrant micro-story—a two-minute, nineteen-second melodrama played out on a stripped-down stage. It’s a shame the spotlight often only landed on the dance, because beneath the spectacle was a band with serious pop songwriting muscle.

Listening Recommendations: Songs of Pastoral Retreat and Observational Pop

- Gerry and the Pacemakers – “I Like It” (1963): Shares the same buoyant, up-tempo beat-pop energy and simple lyrical optimism.

- The Searchers – “Needles and Pins” (1964): Another classic beat-era track with tight vocal harmonies and the same slightly brittle, treble-heavy production.

- Herman’s Hermits – “Silhouettes” (1965): Features a similar narrative focus on unrequited love and a slightly geeky, earnest vocal delivery.

- The Swinging Blue Jeans – “Hippy Hippy Shake” (1964): Highlights the raw, driving rhythm that characterized the early, pre-psychedelic Manchester/Mersey scene.

- The Fourmost – “Hello Little Girl” (1963): A straightforward, melodic Lennon-McCartney composition delivered with the lighthearted sincerity typical of this era’s non-rebel bands.

You can listen to the original 1964 single “Over You” by finding this classic Freddie & The Dreamers song on YouTube.