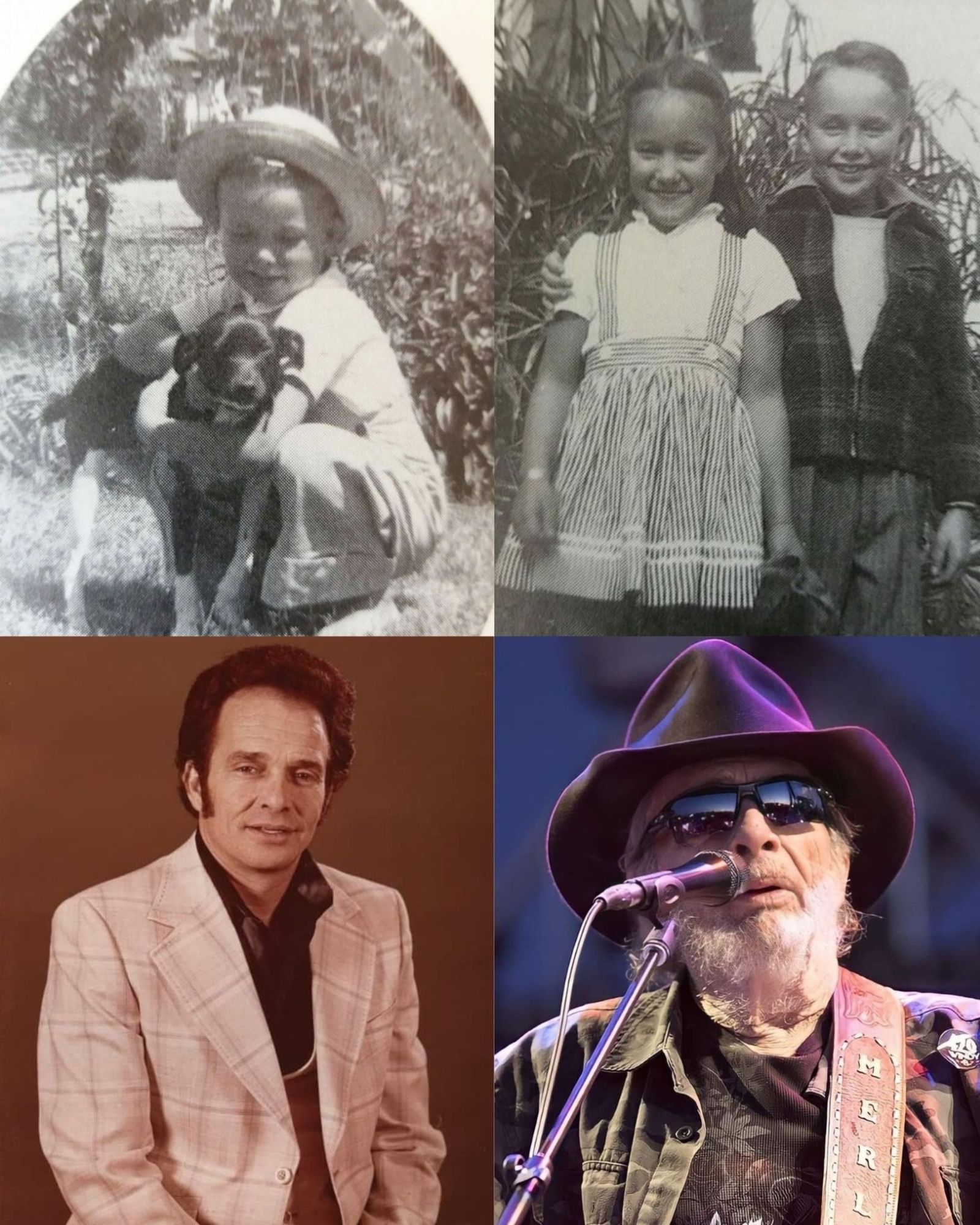

From the boy holding a small dog in the backyard of Oildale, to the rebellious young man locked up in San Quentin, to the artist standing on stage with a guitar bearing his name — Merle Haggard’s journey was never a smooth road. He grew up in a cramped wooden house after losing his father at an early age, watching his mother work tirelessly to keep the family afloat. His troubled years led him into prison, but it was behind those bars that Merle discovered something that would save him: music. From the steel gates of San Quentin, he emerged — carrying a voice carved from life itself. Hungry Eyes, Mama Tried, Sing Me Back Home… These aren’t just songs — they’re fragments of memory. They’re the stories of working-class struggle, of a mother’s resilience, of prisoners who had lost their way but not their dignity. Merle’s voice didn’t decorate the truth — it testified to it. Raw, unfiltered, and deeply real.

I first heard “Sing Me Back Home” the way many great country songs arrive—in the quiet between chores, at an hour when your mind finally sits still. The track doesn’t push itself into the room. It floats in with the surety of a chapel bell, a slow toll that says: listen closely, this matters.

Merle Haggard recorded the piece at the height of his early Capitol run, and its life is entwined with the 1968 album that took its name, Sing Me Back Home, produced by Ken Nelson. It followed Branded Man and helped define a sequence of records that made Haggard the quiet center of the Bakersfield sound, the place where twang, empathy, and plain speech met without fanfare. The single itself arrived in late 1967, then anchored the album released January 2, 1968, on Capitol.

Context matters here because Haggard was moving from promise to authority. The Strangers—his road-and-studio band—were no mere backing unit; they were co-authors of feel. By this point, Roy Nichols had honed his Telecaster’s quicksilver runs, Norm Hamlet’s steel could suggest tears without ever turning maudlin, and George French’s piano slipped in a faint gospel tint. These aren’t just colors in the margin; they are the hinges upon which the song’s tenderness swings open. Personnel credits for the album list Haggard on vocals and guitar, with Nichols (guitar), Hamlet (steel), French (piano), and the rhythm section grounding the space between breath and beat.

What the record remembers—and what listeners often feel before they know the facts—is that “Sing Me Back Home” grew out of an image Haggard carried from San Quentin: an inmate being led to his final moments. In his accounts, that man was Jimmy “Rabbit” Kendrick (often spelled “Kendrick” or “Hendricks” in secondary sources), a figure whose fate clarified the stakes of mercy in Haggard’s imagination. Even when writers parse the details differently, the consensus is stable: a real person’s last walk imprinted itself on Haggard and became the song’s solemn spark.

The sound is remarkably restrained. Haggard’s voice doesn’t oversell the pain; it sits forward in the mix with an unforced authority, drawing you into phrasing that seems to exhale compassion with each line. The Strangers play like they know the lyrics carry their own weight. Listen to how the steel’s sustain lingers a half-breath beyond the vocal, how the guitar replies without chatter, and how the piano’s chordal touches sketch a sanctuary in miniature. The band resists crescendo. Dynamics tighten not through volume but through patience—short swells, gingerly placed fills, and the discipline to leave open air around the singer.

It is a rare thing for a country record to feel both like a bench-side confidant and a public prayer. The track manages that duality by living in two rooms at once. On one side, you hear Bakersfield clarity: ironed rhythms, economical picking, everything a little drier than Nashville’s string-sweetened gloss of the era. On the other, a hush: the room tone seems to curve its shoulders inward, as if the studio itself knows to soften its echoes. The result is a piece of music that moves on human breath, not studio tricks.

Haggard’s delivery is a study in kind authority. His consonants are carefully turned but never fussy, his vowels open just enough to carry the tone without bleeding sentiment. There’s a slight dip on certain syllables—an unhurried fall that suggests both acceptance and ache. Even his micro-pauses feel ethical, as though he’s granting the subject the dignity of silence between thoughts. You can diagram the melody and discuss structure, but the emotional architecture is all in the phrasing. He never shouts. He simply holds the room.

“Sing Me Back Home” sits at a key inflection point in Haggard’s career arc. The single topped the country chart early in 1968, confirming that his voice—stoic, exact, unpretentious—could carry a story this grave and still cross radio with ease. The album itself became a number-one country LP, consolidating his early run with Capitol and extending his range from honky-tonk storyteller to moral witness.

From an arrangement standpoint, what keeps the record evergreen is its balance of detail and space. The rhythm section doesn’t advertise itself; the bass walks with a subdued purpose, and the drums mark time with brushes and light sticks, more heartbeat than metronome. The guitar is a neighbor who knows when to speak—short phrases, a bend that lands like a nod, a fragment of a reply rather than a speech. The piano appears like stained glass in late light: small panes of color that turn the same room into a gentler place. Together, they make a frame that never crowds the portrait.

There’s also the matter of timbre. Much country of the era relied on strings to announce grandeur. Haggard and Nelson knew better than to gild this. If the story is already sacred, you don’t hang more gold on it; you clear a path to the altar. The premium of this recording is intimacy—an aesthetic that rewards good speakers and good patience in equal measure. If you cue it up late at night on a modest home audio setup, you’ll still hear the performance lean toward you like a confidant, not a broadcaster.

One of the great paradoxes of the song is how mercy arrives through craft. Haggard’s melodic line avoids melodrama, yet the lyric’s plea lands heavier because of that refusal to strain. The Strangers answer with a vocabulary pared to essentials: a steel sigh, a single-note guitar figure, a soft piano chord that hums like the last light through a stained-glass pane. The record accepts sorrow without spectacle. In doing so, it turns grief into a common language.

“Sing Me Back Home” also demonstrates how Haggard’s storytelling scale expanded in this period. He wasn’t just narrating personal trials or barroom regrets; he was addressing a community’s sense of justice and forgiveness. It’s no accident critics place the album among the pillars of his late-60s work, an axis with Branded Man and Mama Tried that maps from stigma to compassion to resolve. That arc isn’t theoretical; it’s audible—ascending levels of empathy layered over arrangements that become more confident about saying less.

A few micro-stories surface whenever I play it for people. One friend, a nurse, told me she hears the song as a bedside hymn: “We ask for the old songs in the last hours because they make the room feel like home.” Another listener, a former corrections officer, said the track reminds him that institutions don’t cancel humanity. He keeps it on a playlist for long drives after night shifts, when the road needs a voice that neither condemns nor excuses, only attends. A third, a church pianist, once put it on while repairing a sticky sustain pedal; she said the steel’s long notes taught her how to let certain chords breathe longer during funerals. Different lives, same hush.

Technically, the recording is an education in how to leave room for the listener. Notice how the steel’s vibrato never becomes syrupy; it’s a slow shimmer, not a wobble. The guitar’s attack is measured—just enough pick to define the edge, then a gentle decay that passes the baton back to the vocal. The piano keeps to midrange voicings; too much upper register would sparkle where the lyric needs candlelight. Each choice suggests a band listening more than playing, which is perhaps the highest compliment you can pay a country rhythm section.

The lyric’s central request—sing me back home—poses an unusual theology of song. Home isn’t a place you drive to; it’s an interior room opened by melody and memory. Haggard knew that from the inside. Whatever debates surround the exact biography of the man who inspired the narrative, the ethical stance remains: in the presence of a life’s last minutes, the right tune can dignify what the law cannot heal. That’s not sentimentality. It’s craft in service of mercy.

Play this through good speakers or, better yet, under studio headphones, and you’ll hear how the performance knits itself together. The reverb is modest; tails fade in a room-sized arc rather than a hall. Haggard sits at conversational distance. Even the small air between phrases becomes part of the meaning, as if silence itself were nodding along. Bakersfield may have been born in barrooms, but here it becomes liturgy—lean, humble, exact.

There’s a temptation with classics to enshrine them, to say: untouchable, museum piece. But “Sing Me Back Home” is not glassed off behind a plaque. It lives when you place it in ordinary hours. Try it while you clean the kitchen and you’ll find your hands slow; try it after a difficult phone call and you’ll notice the phone feels lighter; try it on a Sunday commute and your tires will hum in softer meter. The song alters the temperature of a day.

In career terms, its success was immediate and durable. The single rose to the top of the country chart in early 1968, and the album reached number one as well, confirming Haggard’s authority as a songwriter of public feeling. Decades later, critics still list the track among his most affecting achievements, precisely because it refuses theatrics while touching the unspeakable.

“Sing Me Back Home” doesn’t argue; it attends. It’s the sonic equivalent of someone standing beside you and placing a hand on your shoulder only once. The band knows how not to fill every bar. The arrangement leaves the corners of the room dim. The vocal keeps the light steady. And in that steadiness, the listener finds a kind of permission—to grieve what must be grieved and to carry on with tenderness for those still walking.

“Mercy enters the room not with a crash but with a chair pulled close and a voice that remembers your name.”

One reason the record remains persuasive is its refusal to confuse simplicity with smallness. The harmony part—often Bonnie Owens in this era—doesn’t climb over the lead; it shadows just enough to make the melody sound companioned. The rhythm doesn’t chase push; it allows procession. Everything is subordinate to the central human act of singing someone toward home.

This is music built to last because it is built on attention. The arrangement, the placement of each instrument, the patience in the time feel—none of it draws attention to itself until you listen with care. Then you hear the sturdiness of the carpentry. You hear how a Telecaster’s glint can sound like memory’s edge, how a steel’s shimmer becomes the shape of a prayer, how a piano’s midrange chord can warm a cold story without ever sweetening it beyond truth.

If the first listen gives you the gist, the twentieth gives you the grain. That’s when you notice how the final refrains stack not by volume but by acceptance, how the band yields one last little corridor of air for the vocal to walk through. The fade doesn’t close a door; it leaves it ajar. Which is fitting. Some songs don’t end so much as they keep watch.

And so the track earns its place—not as a relic, but as a companion. When people talk about Haggard’s early Capitol years, this is the song that proves how economy can bear transcendence, how honesty can carry more freight than ornamentation, and how a compassionate eye can turn a hard scene into a usable kind of grace.

Before you move on, let it play again. Not to decode it further, but to inhabit its room. There’s nothing grand here, only a voice, a band, and the long kindness of a melody. That is more than enough.