The year 1966 was a seismic shift. The world felt the tremor of Revolver and Pet Sounds, the new sound a complex tapestry of studio wizardry and cultural rebellion. Yet, across the Atlantic, in the UK charts, a different kind of sound held court, one that was perhaps more ancient and certainly more theatrical. It was the sound of opera, disguised as pop: the glorious, unapologetic agony of Gene Pitney.

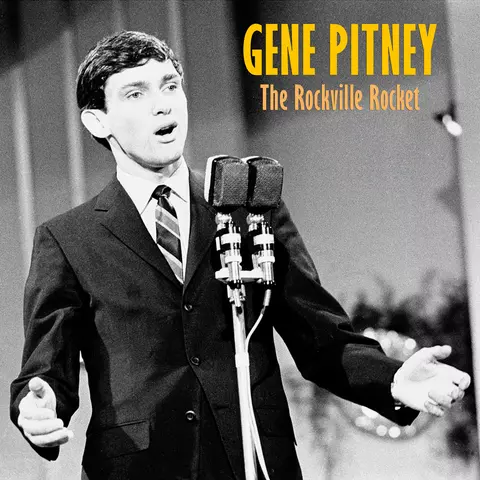

His US popularity was beginning to wane, a pre-British Invasion figure finding his soulful, high-drama style momentarily out of step with the burgeoning psychedelic and folk-rock movements. But in Britain, Europe, and especially Italy, Pitney remained a titanic figure. His audience there still craved the full, orchestrated heartache he delivered with impossible vocal control. They demanded melodrama, and Pitney, the Rockville Rocket, was ready to launch.

This context is vital to understanding the brilliance of “Nobody Needs Your Love” (often appended with More Than I Do). Released as a single in 1966 on the Musicor label in the US (though reportedly not promoted as a single there, only appearing on the Backstage (I’m Lonely) album), and as a wildly successful single on Stateside in the UK, this piece of music is a testament to two distinct mid-sixties phenomena: Pitney’s enduring, almost cult-like appeal abroad, and the early, insightful genius of a then-fledgling songwriter named Randy Newman.

It is Newman’s composition that provides the skeletal sorrow. The lyrics are a straightforward, desperate plea: a man whose identity is entirely wrapped up in his unrequited devotion. “If you don’t want me, I don’t wanna live,” Pitney cries, a line that manages to sound less manipulative and more profoundly, tragically literal coming from his lips. The song is a succinct statement on absolute need, a four-line biography of a broken heart.

The arrangement, credited to the masterful Garry Sherman, is what elevates the song from mere pop balladry into a cinematic scene of utter despair. It’s a perfect example of the ‘grown-up’ side of the Brill Building aesthetic, blending a solid rock-and-roll rhythm section foundation with an almost Mahlerian swell.

The opening is immediately immersive. A rapid, syncopated drum figure, played with brush strokes that quickly transition to a driving backbeat, sets a restless tempo. The brass hits—sharp, quick bursts—punctuate the first few seconds like anxious gulps of air. But it is the strings, Pitney’s signature sound, that take the emotional lead. The violins don’t simply pad the melody; they are an active, weeping voice, their sustained, rich texture providing the velvety backdrop for Pitney’s tenor.

The piano work is subtle, playing a crucial, almost hidden role in binding the low-end harmony to the melody. It’s less a featured instrument and more the foundation that prevents the large orchestration from dissolving into air. It gives the piece its structural integrity, a dense, dark anchor beneath the vocal flight. Similarly, the guitar is an understated presence, likely an electric rhythm guitar strumming in the background, offering harmonic fills rather than flashy solos. The overall production, which the singer himself reportedly oversaw alongside Sherman, is rich, dense, and perfectly tailored for the premium audio systems of the day—a full-spectrum sound that fills the room.

Pitney’s vocal performance, of course, is the event. His voice—a rare blend of operatic training, rock-and-roll grit, and a distinctive, powerful vibrato—was made for these grand gestures. He begins the song in a relatively controlled mid-range, pleading with earnestness. But by the time he reaches the chorus, the emotion bursts through. The famous high-C-sharp, his signature note of catharsis, arrives with a near-shattering intensity on the word “I,” as in, “Nobody needs your love more than I do.” It’s an act of controlled desperation, a man standing at the precipice of emotional collapse, perfectly captured on tape.

“He turns a simple pop song into a short, harrowing tragedy played out in three minutes and twenty seconds of sound.”

It’s a marvel how the dynamics mirror the psychological state of the singer. The music builds, layer by layer, with an almost frantic energy. The repeated phrasing of the title line in the outro is where the song truly dissolves into a state of magnificent obsession. Pitney’s voice multi-tracks itself, a relentless chorus of sorrow that fades out not because the feeling has ended, but because the tape machine simply ran out of room for the tears. This final, echoing chant is the perfect sonic device to imply an unending, looping misery.

In an era of increasing lyrical sophistication and studio experimentation, Pitney stuck to a style that was, by then, already considered démodé by many American critics. He took the grand, orchestral pop arrangement—the “Wall of Sound,” the Bacharach/David classicism—and made it wholly his own by injecting his unique, tear-soaked Italian-American soul. His commitment to this style is why the US album, Backstage (I’m Lonely), and the singles like this one, found little purchase in America but flourished so completely overseas, leading to the peculiar transatlantic career arc that defined his later years. It’s a compelling contrast: a sound deemed passé in New York was pure gold in London.

The song’s UK success, climbing into the upper reaches of the chart, is a quiet marker for how much the British public valued that strain of dramatic, European-tinged pop. It’s also a powerful early indicator of Newman’s talent. Before the satirical, character-driven narrative of his famous solo work, Newman penned these perfect, miniature portraits of romantic collapse, showcasing a surprising empathy for the plight of the theatrical pop singer.

Today, listening to this track through a good pair of studio headphones reveals the astonishing clarity and depth of the 1966 recording. You can hear the room, the separation of the orchestra, and the sheer power of Pitney’s uncompressed vocal, a raw, undeniable testament to the era’s unique recording philosophy. It’s a time capsule of a sound that never compromises, that never whispers where it can roar.

“Nobody Needs Your Love” is more than a forgotten hit; it’s a brilliant, overwrought monument to mid-century heartbreak, cemented in place by the synergy of a powerhouse singer, a visionary young writer, and a perfect, tear-stained arrangement. It invites you to lean in and indulge in the exquisite agony of a man who simply cannot go on without a love he will never have.

Listening Recommendations

- Gene Pitney – Just One Smile (1966): Another masterful, lushly arranged Randy Newman composition from the same year, demonstrating their powerful chemistry.

- Scott Walker – The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore (1966): Shares the same sense of epic, orchestrated despair and theatrical vocal delivery in a contemporaneous UK hit.

- Dusty Springfield – You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me (1966): Features a similar sweeping orchestral drama and an emotionally intense, soaring vocal performance.

- Roy Orbison – Crying (1961): The quintessential antecedent for Pitney’s style, showcasing the operatic, high-tenor agony over a classic pop structure.

- The Righteous Brothers – Unchained Melody (1965): Another Phil Spector-influenced, ‘Wall of Sound’ track utilizing immense dynamic range and a male vocal of overwhelming emotional depth.