The air in the room is heavy, not just with cigarette smoke and cheap wine, but with the suffocating weight of an impossible decision. The city outside is a blur of neon and rain—a cinematic backdrop to a private, shattering moment. I can see the cracked vinyl spinning on the turntable, catching the dim light. It is 1968, and the radio waves, still clinging to the grandiose arrangements of the early sixties, deliver a voice that is both a plea and a triumphant cry: Gene Pitney’s take on “Yours Until Tomorrow.”

This piece of music, penned by the era’s most formidable songwriting duo, Gerry Goffin and Carole King, is not just a song; it’s a script for a three-act tragedy contained within three minutes. It is a testament to the dramatic power of the Brill Building school, filtered through the uniquely operatic sensibility of Gene Pitney. While the song had been previously recorded by others, notably Dee Dee Warwick, Pitney’s 1968 single on the Musicor label claims it with a towering, almost frantic emotionalism that few contemporaries could match.

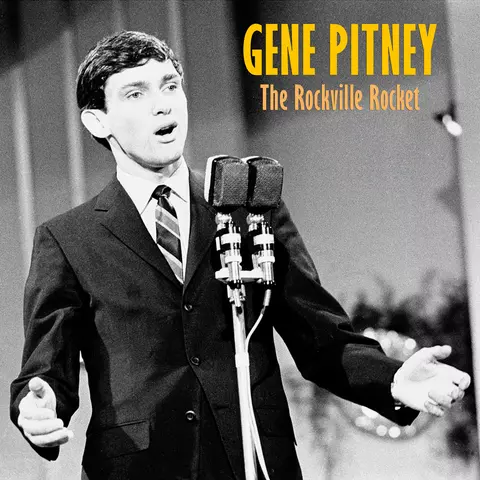

The track arrived late in Pitney’s astonishing run of American chart hits, just as the musical landscape was fracturing under the weight of psychedelia and roots rock. Pitney, the “Rockville Rocket,” had built his career on spectacular, dramatic ballads like “Town Without Pity” and “I’m Gonna Be Strong,” establishing himself as the era’s chief chronicler of romantic, exquisite agony. In the U.S., “Yours Until Tomorrow” was not a major pop breakthrough, but it resonated strongly enough across the Atlantic to become another fixture in his long, successful UK chart run, confirming his enduring popularity in Europe even as American tastes shifted.

The Anatomy of Agony: Sound and Arrangement

The record begins not with a whisper, but with a statement. A sustained, lush string chord hangs in the air, creating an immediate, almost suffocating atmosphere of inevitable doom. This is Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound aesthetic stripped down to its elegant core, focusing its energy into a precision strike of pathos.

Beneath the soaring, mournful strings, the rhythm section enters with a slow, deliberate march—a heartbeat counting down the stolen hours. The bassline is deep and warm, anchoring the entire arrangement while the drums are mixed with a judicious amount of echo, providing a spaciousness that suggests the vast, empty future awaiting the protagonist. A subtle, high guitar figure provides a shimmering counter-melody in the background, a small, bright detail that contrasts heartbreakingly with the overwhelming gloom.

At the emotional center of this arrangement is the piano. It moves from simple, gentle chords in the verses, offering Pitney a soft landing, to powerful, almost percussive declarations in the chorus. It acts as a conversation partner to Pitney’s voice, a solid bedrock of musicality that allows his famously elastic tenor to soar and plunge without losing its anchor.

When Pitney’s voice arrives, it’s a masterclass in controlled desperation. He is singing the story of a man begging for one single night of forbidden love before his partner returns to their “real world” commitment. His vibrato, often criticized as excessive, here feels entirely earned—a tremor of vulnerability and barely contained mania. He doesn’t just sing the words; he italicizes the emotion, drawing out syllables on lines like, “My heart overflows with e-mo-tions I just can’t control.”

The crescendo on the chorus, “Let me be yours until tomorrow,” is one of the most stunning examples of pop-operatic staging in the late sixties. The strings sweep up dramatically, the brass hints at a majestic, yet doomed, fanfare, and Pitney hits a high, sustained note that is pure, unadulterated yearning. It’s glorious and over the top, the sound of a man who knows he is losing everything but will buy one final memory with the coin of his soul.

The Final Hour: Pitney’s Career Arc in Miniature

This magnificent, desperate ballad is an accurate sonic snapshot of Pitney’s career around 1968. He had moved from his early self-penned hits to become a crucial interpreter of the finest contemporary songwriters, taking on material from Randy Newman, Goffin-King, and the Bacharach-David team. His records for the Musicor album label were consistently grand, sophisticated, and unafraid of maximalist drama.

He was the rare American star who managed to not only survive but thrive during the initial British Invasion, often finding more success in the UK and Europe than in his home country. “Yours Until Tomorrow” is a bridge between the classic Brill Building balladry and the darker, more emotionally complex arrangements that would follow. Listening to it now, through a pair of high-fidelity premium audio speakers, the clarity of the production shines through, revealing the meticulous layering of instruments that builds to that peak of catharsis.

“The way he could elevate a simple pop melody into a confession of epic, life-or-death consequence was truly unique.”

Pitney never wavered from his dramatic instinct. While the broader musical current moved toward singer-songwriters playing their own guitar lessons and folk-rock simplicity, Pitney doubled down on the spectacle. This commitment is what makes him timeless for connoisseurs of elegant melodrama. He understood that a three-minute pop song could be as emotionally exhausting and fulfilling as a stage play.

Epilogue: One Last Night, Forever on Wax

The song’s power lies in its structure—the cyclical nature of the verse and chorus reinforcing the central, agonizing bargain. The final verse, the quietest moment, feels like a sudden return to reality, a moment of sober dread before the final orchestral swell. “Tomorrow the real world / Will come crashing down on me / I know I must lose you / And that’s the way it has to be.”

This song is the soundtrack to every doomed, late-night rendezvous; every choice made in the blinding heat of the present, knowing the cold light of the future will demand its price.

Imagine a young woman in 1968, driving an open-top convertible down an empty coastal highway at 2 AM, the radio volume cranked to maximum. The music isn’t simply playing for her; it’s speaking to her, giving voice to a turmoil she can’t articulate. Or consider the quiet listener decades later, slumped in an armchair, the weight of their own compromised history pressing down, finding strange, beautiful validation in the exquisite pain of this recording. This is the enduring genius of Gene Pitney: he gave emotional scale to private grief. He took a universally understood moment of painful, temporary grace and rendered it immortal.

The song fades out with the echo of the final, desperate plea still ringing. It doesn’t offer resolution, only catharsis. It is a masterpiece of pop agony, a monument to the things we surrender for just one more day of belonging.

Listening Recommendations

- “Just One Smile” – Gene Pitney (1966): Another masterful, orchestral ballad by Pitney, this time a poignant cover of a Randy Newman composition, sharing the luxurious, sweeping arrangement style.

- “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore” – The Walker Brothers (1966): Features the same grand, melodramatic orchestral sweep and devastating vocal delivery, cementing the “baroque pop” style.

- “She’s a Heartbreaker” – Gene Pitney (1968): Pitney’s other major 1968 single, demonstrating his successful foray into a more R&B/soul-inflected sound while maintaining vocal power.

- “What The World Needs Now Is Love” – Jackie DeShannon (1965): A different emotional tone but shares the characteristic dynamic contrast and soaring orchestration arranged by Bacharach and David’s orbit.

- “Where Do I Begin (Theme from Love Story)” – Andy Williams (1970): For fans of the tragic, string-heavy, cinematic balladry style that Pitney perfected, this is the logical, lush successor.

- “Wichita Lineman” – Glen Campbell (1968): While structurally different, it shares the same profound melancholy and ability to convey a deep, personal sense of longing within a richly produced soundscape.