George Strait’s “The Cowboy Rides Away” is the kind of goodbye that doesn’t slam the door; it simply turns up the collar, tips the brim, and moves on without spectacle. I remember first hearing it on late-night radio, windows cracked, the road emptying into darkness like a long cattle trail. The song didn’t plead. It didn’t lecture. It kept pace, as if the heart had learned—after many miles—how to keep walking.

The track arrived in January 1985 as the second single from Strait’s fourth studio album, Does Fort Worth Ever Cross Your Mind, co-produced with Jimmy Bowen and released on MCA. It’s one of those career-pivotal weeks in country history: when Strait, barely a few years into his run of hits, solidified his neotraditional stance on the radio dial, favoring fiddles and steel over then-fashion synth sheen. The single would become a Top 5 entry on Billboard’s Hot Country chart in the U.S. and reach the Top 3 in Canada, the sort of broad reception that quietly tells you a story has landed where it needs to. Wikipedia+1

There’s important context here. The album that housed it marked Strait’s first production pairing with Bowen, a seasoned Nashville figure renowned for letting performers breathe inside arrangements rather than gilding them. Many observers have noted that this partnership helped define Strait’s economical, tradition-first studio identity going forward. Recorded in Nashville in mid-1984, the record’s sonic footprint favored live-room energy, unfussy miking, and playerly interplay over flash. Wikipedia+1

Written by Sonny Throckmorton and Casey Kelly, “The Cowboy Rides Away” has a narrative as old as the West and as current as anyone facing an ending they can neither fight nor fix. The cowboy isn’t leaving in triumph; he’s retreating with hard-won clarity. The lyric sketches a relationship that’s circled the corral too many times, the dust finally settling into a plain, painful acceptance. Strait’s performance makes room for that acceptance by refusing to crowd it—phrases hang just long enough to sting, but never long enough to wallow. Wikipedia

Musically, the arrangement tells its own pared-back story. The rhythm section locks into a mid-tempo lope, the kind of understated motion that suggests distance rather than drama. A high, mournful steel guitar braids around the vocal like dusk light slipping through fence boards. The fiddle lines are conversational—never a showpiece, always a witness—answering Strait’s phrases with a nod of recognition. Acoustic strums lay the bed; electric filigree keeps the horizon glinting. If there’s a faint keyboard pad or a spare bar of piano, it’s subtle, tucked in like the brush of wind against denim.

What strikes me on repeated listens is restraint. There’s no big modulation, no dramatic drum fill to push the chorus uphill. The structural movement comes from dynamics and density—the way the band tightens slightly into the hook, then releases as the verse returns to low flame. Strait sings in the pocket, behind the beat by a breath, trusting that listeners will lean forward instead of being yanked along. That’s confidence, and it’s also craft.

The mic perspective feels close but not claustrophobic, a studio intimacy that hints at a singer standing half a step back from the capsule, letting air do some of the work. On the steel, the sustain decays into a soft halo; the reverb tail is short, more room than plate, letting articulation stay crisp. Even the drum kit—the light thump of the kick and the dry hush of the snare—suggests carpeted floors and baffled corners rather than cavernous echo. These are small choices, but they matter: they pull the song inward, where departures actually happen.

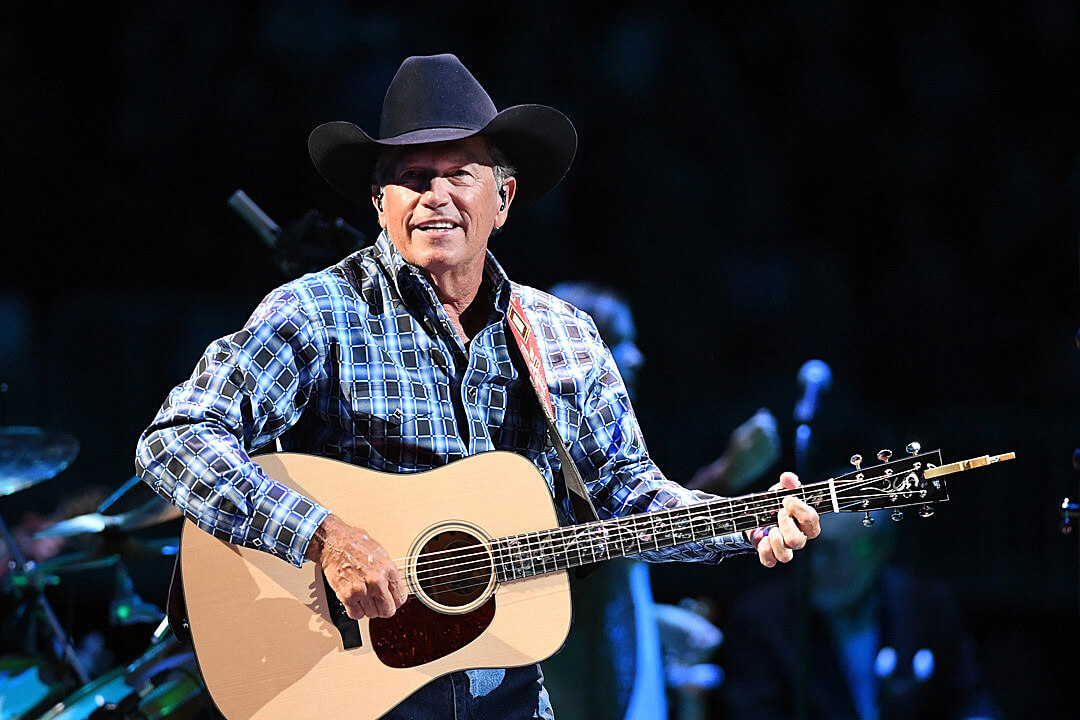

Every George Strait hit becomes part of a longer arc, and this one gained a second life as his signature closer onstage, eventually lending its name to his 2013–14 farewell tour. When he sang it at his final tour stop at AT&T Stadium on June 7, 2014—before a reported stadium-record crowd—the metaphor folded into reality: the cowboy really did ride away, at least from the relentless churn of the road. That moment retroactively deepened the studio cut, proving how a three-minute country single can accrue meaning over decades until it feels like folklore. Wikipedia+1

As a piece of music, it also models Strait’s interpretive philosophy. He’s not a vocal acrobat. His instrument is presence, the way tone and timing suggest a life lived beyond the microphone. Listen to the way he rounds the edges of the vowels in the chorus, as if smoothing down a rough cedar post with the palm of his hand. Hear the almost-spoken glide at the end of lines, the refusal to lean into melisma where a plain note will do. The emotional temperature stays steady, which paradoxically makes the lyric burn hotter.

I sometimes teach young players that country gravitas isn’t about singing louder; it’s about making listeners believe you’d say the words even without a melody. Strait embodies that. The edges of his phrasing feel weathered but not weary, and when the band drops to a hush for a beat before the chorus returns, the silence is as eloquent as any lick.

If you sit with the track on good studio headphones, a few production textures stand out. The steel harmonics kiss the top of the spectrum without ever turning brittle. There’s a slight glue in the midrange—fiddle, vocal, and snare sitting together—suggesting careful EQ carving that favors warmth over glare. And beneath it all, the bass holds a sure line with minimal ornament, giving the drums something to lean on but never insisting on attention. None of it is designed to impress in the moment; all of it is designed to last.

Consider how the song fits in Strait’s catalog around that time. In 1984 and 1985 he was moving from rising star to institution, stacking hits while bucking the pop-country trends that dominated much of the decade. The chart story on this single—a solid Top 5 in the U.S., a notch higher in Canada—mirrors the aesthetic: substantial, unhurried, inevitable. You don’t sense an artist chasing; you sense an artist choosing, and country radio choosing with him. Wikipedia

Because the composition is so lean, small performance decisions carry weight. The opening measures don’t over-announce themselves; they simply begin, like hooves finding the trail at first light. The first verse functions almost like a whispered confession—a few lost fights, a few tried repairs, and then the recognition that dignity sometimes means departure. The chorus, to my ears, doesn’t explode; it settles. It accepts. That’s the record’s mature brilliance: it recognizes that some crescendos happen internally.

I’ve heard the song in three different rooms that changed its meaning for me.

One: a dim café after a long winter afternoon, rain making watercolor of the street outside. A couple near the back table didn’t speak for several minutes. When the chorus arrived, they looked up at the same time and nodded. Not resignation—recognition. The song gave them neutral ground, a place to think in parallel without accusation. A goodbye can be merciful when it refuses to humiliate.

Two: a crowded bar on a Friday when nobody wanted to go home. A local band played it without flash—two acoustics, a small amp, a modest steel player who never once reached for pyrotechnics. The dance floor thinned to patient two-steps. I noticed how the lyric made the room gentler, as if everybody agreed to keep each other’s stories intact.

Three: a highway rest stop somewhere west of Amarillo, the kind of night where the sky feels like a ceiling has been removed. A trucker had the song drifting from a cab. He leaned against the door, watching the pumps. When the line about riding away returned, he smiled—not sad, exactly; more like someone who knows departure can be a promise as well as an ending.

“Restraint is the record’s secret engine: it moves the heart by refusing to shove it.”

When I zoom in on instruments, the track’s equilibrium becomes even clearer. The guitar parts are unhurried, supportive, like good friends who don’t overtalk a hard moment. A few single-note climbs, a measured strum, nothing that jostles the narrative off center. The fiddle operates as a second narrator, answering the vocal with short phrases that feel like side glances—comforting, not prescriptive. And the steel, when it lifts into that keening overslide just before the chorus resolves, paints the horizon in two strokes: pain and release.

It’s tempting to fantasize about alternate versions—bigger string sections, stacked harmonies, a longer outro. But the record’s intelligence lies in its refusal to gild. Strait and Bowen keep the frame narrow; the picture gains force because nothing distracts from the figure moving away from us down the trail. In a decade when production often chased gloss, this track stood its ground. The result is a single that still feels contemporary because it is unafraid of space.

From a listener’s standpoint today, the song has acquired a ceremonial glow thanks to its role closing Strait’s concerts and lending its name to his final tour. That legacy never overwhelms the original cut; it simply casts a longer shadow, reminding us that country’s most durable emotions are the ones spoken plainly. When the stadium lights went down in Arlington in 2014 and the last chorus receded into 100,000 quieted voices, the three-minute studio recording from 1985 felt like a seed that had found its vast, improbable field. Wikipedia+1

A word about craft for musicians who study the bones of songs. This isn’t a piece you transcribe for pyrotechnic solos or sudden metric tricks. But if you’re the sort who likes to mark up sheet music to track dynamics and phrasing, you’ll find a masterclass in moderation—swells that arrive a bar later than you expect, breaths that create humane tension, instrumental replies that never crowd the singer. It’s not simple because it lacks complexity; it’s simple because the complexity has been disciplined into service of feeling.

Even in the broader Strait discography, the track remains a north star for balance: classic Western narrative, modern radio economy, emotional clarity. That’s why it keeps finding new ears—through old CDs, catalog streams, live compilations, or a parent’s well-worn jukebox memories. The song doesn’t need an introduction anymore. It requires a quiet room and enough honesty to let it work.

In closing, I’ll underline what makes “The Cowboy Rides Away” endure. It respects both parties in the story. It honors the distance between spectacle and truth. And it shows how a country singer at the crest of his ascent could already sound like someone who had nothing to prove. The trail it leaves behind is not a wound; it’s a map. Revisit it with a clear head and a steady heart, and the road it points to may surprise you.

Listening Recommendations

– George Strait — “Does Fort Worth Ever Cross Your Mind”: Another mid-’80s Strait essential with the same unfussy production and a more overt hook. Wikipedia

– Alan Jackson — “Here in the Real World”: Early-’90s neotraditional polish with steel and fiddle carrying a stoic heart.

– Randy Travis — “On the Other Hand”: A slow-burn moral crossroads rendered with unadorned grace.

– Reba McEntire — “Whoever’s in New England”: A restrained arrangement framing adult heartbreak with narrative finesse.

– Brooks & Dunn — “Neon Moon”: A loping nocturne where steel guitar and space define the ache.

– George Strait — “I Cross My Heart”: Later-era Strait, bigger sweep but the same poised sincerity that rewards a re-listen.