The first time I really listened—not just heard, but listened—to “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” it was after midnight, a low lamp, the day’s noise finally settling. The opening bars felt less like a record starting and more like a curtain drawing back. You sense a hush, an intake of breath, a long hallway of reverb that seems to lead you toward something both private and public at once. It’s a paradox only the great pop moments achieve: a piece of music intimate enough to sit with you in a quiet room and yet vast enough to carry a stadium.

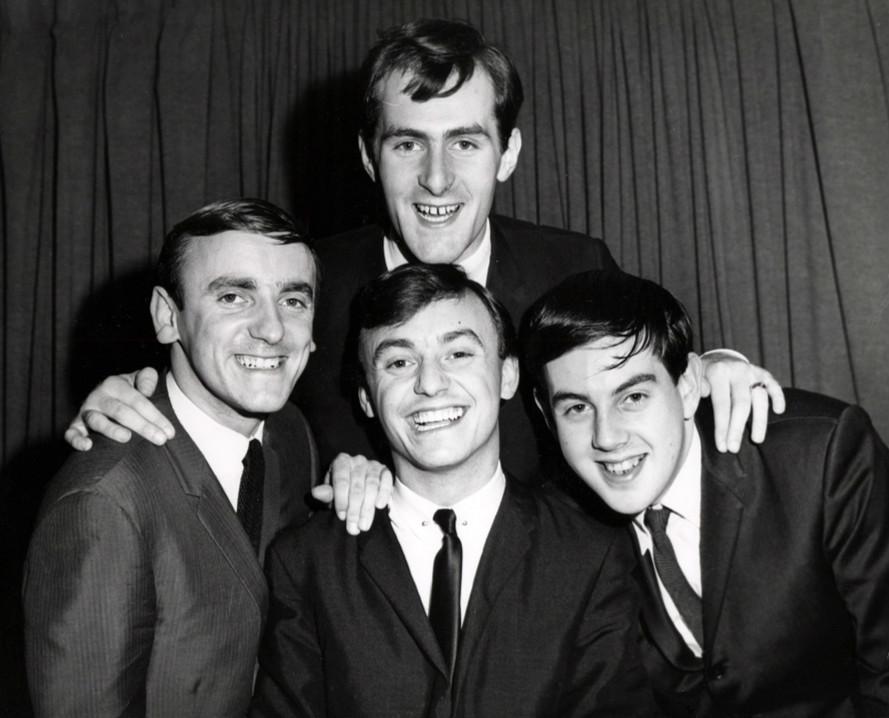

The origin story is well known but still remarkable. Rodgers and Hammerstein wrote it for Carousel in 1945—a benediction sung against calamity. Nearly two decades later, Liverpool’s Gerry & The Pacemakers, produced in their early run by George Martin, recast it as a beat-era devotional and, in doing so, rewired the song’s social life. Their 1963 single rose straight to number one in the UK, a bridge between theater aisle and football terrace, between the personal and the collective. The label on that run of hits was Columbia (an EMI imprint), and its ascendance made the group the first act to see its first three singles all go to UK No. 1.

But singles are only half the story; albums are where songs learn to sit among neighbors. “You’ll Never Walk Alone” wasn’t left floating as a stand-alone; it took a seat on the band’s 1963 debut album How Do You Like It?, nestled among rhythm-and-blues covers and Merseybeat stompers. That context matters. Surrounded by up-tempo fare, its stately gait becomes more pronounced, almost ceremonial, a point of stillness in a busy room. You can feel the sequencing logic: speed, swing, swagger—and then this solemn procession through the center of the LP.

Listen to the arrangement and you’ll hear the group work with a restraint that speaks volumes. The rhythm section sits back, more heartbeat than backbeat. The strings, arranged to swell without smothering, arrive like weather: first a breeze, then a gathering front, and finally a clearing, sun after storm. Gerry Marsden sings with a plainspoken vibrato—never showy, never undercooked—phrases shaped at the ends, consonants softened so the vowels can carry. The guitar doesn’t jangle; it glints—small arpeggios and supportive figures that keep the song’s spine straight while the strings do the lifting. When piano peeks through, it’s the kind of unobtrusive doubling that locks harmony to breath, wood and wire to human voice.

The performance builds without manipulation. If there’s a modulation it’s executed like a camera dolly, not a jump cut, and the dynamic arc is all human scale: verses in the chamber, chorus in the nave. You imagine the microphones placed to capture space as instrument—room tone as compassion. The reverb tail isn’t glossy; it lingers like a thought you’re not ready to lose.

What always gets me is the tempo choice. A notch too slow, and you risk sentimentality; a notch too quick, and courage becomes pep talk. Here, the pulse feels like the walk in the title—steady, unhurried, shoulders squared. The entire band understands that walking is the point. This is not a sprint to transcendence but a measured crossing of a difficult street.

“Restraint turns into radiance not by adding more sound, but by letting the same notes stand up straighter.”

By any cold metric, the record worked. It topped the UK singles chart, and you’ll find its chart life echoed in Australia, Ireland, and New Zealand. But the more significant afterlife came a few miles from the band’s home turf, when Anfield made the single a ritual. In Liverpool the song stopped being just a track; it became a civic hymn. It’s sung before kickoff, in sorrow after disaster, in joy after improbable comebacks. The club even etched its promise into its official motto. Culture critics sometimes overstate these transformations, but not here: the record’s success and its local authorship created a feedback loop between vinyl and voices that few songs ever achieve.

What fascinates me is how a show tune’s architecture survived the pop arrangement intact. Rodgers and Hammerstein wrote a melody built to hold grief and resolve simultaneously; it’s a line that climbs while looking back. Gerry & The Pacemakers didn’t mask that theater spine. They respected it, allowing orchestration to support, not recast, the geometry. That’s why the pathos lands without melodrama. You hear the consonance between stage and street: the theater teaches projection; the terrace teaches response.

One subtle craft choice: the breath between “walk on” and “with hope in your heart.” Many singers rush that intake to stretch the next phrase. Marsden lets the air complete the thought. It’s as if the song acknowledges the human body—lungs, ribs, diaphragm—as part of the instrument. The phrasing reminds you that courage is not abstract; it is breath managed under pressure.

Consider the mix perspective. Vocals are forward, yes, but not isolated; you still perceive a halo of room. The strings aren’t syrupy; their timbre leans closer to church than cinema—bow hair, not sheen. When the drums surface, they do so with brushes or soft sticks, an undercurrent rather than a command. If you’re listening on studio headphones you’ll notice the way the sustained strings knit with the voice on the long vowels—the kind of low-level detail that transforms a familiar track back into a living performance.

There’s a temptation to make this all about football, to reduce a wide human thing to ninety minutes. Yet the song’s reach has always been wider. During the pandemic, communities across Europe repurposed it as a salute to essential workers and a balm for isolation. That’s because the lyric—call it secular gospel—speaks to any public moment when fear comes into view and we decide to face it together. The Pacemakers’ version works here because it frames courage as a collective act without ever shouting.

In the band’s career arc, this moment was a culmination and a turning. Their early singles had already set records—three consecutive UK number ones—and “You’ll Never Walk Alone” sealed their early dominance. It’s easy to forget how quickly this happened: the British beat boom was a cascade. Under the guidance of manager Brian Epstein and producer George Martin, Gerry & The Pacemakers staked out a lane adjacent to their friends and rivals in The Beatles: less irony, more earnestness; fewer sly winks, more open-armed melody. The single might be a cover, but it crystallized the band’s own face: sincerity as signature.

The Liverpool connection, of course, is more than a trivia note. There are stories—some from players—of Gerry Marsden sharing an advance copy with Bill Shankly in the summer of ’63 and the manager being immediately taken by it. Whether the details shift depending on who’s remembering, the thrust is consistent: the song left the record shop and entered the rituals of a city. Soon the Anfield DJ’s habit of spinning the week’s chart cracked open a new tradition—the crowd sang the No. 1, then kept singing when it left the charts. Longevity by communal fiat.

What about the song’s body, that tactile thing we experience through speakers? Listen closely to the way the strings and voice interact on the final chorus. The strings rise first, like a hand placed on a shoulder. The voice follows, not by getting louder but by adding a little grain to the tone. The arrangement widens then tightens, and when the last chord resolves, the release feels earned. The record doesn’t manufacture catharsis; it allows it.

I think often about how the arrangement keeps faith with the lyric’s verbs: walk, blow, sky, storm. The textures conjure weather and motion. The band resists any breakbeat or dramatic drum fill that would force a climax; instead, they let the harmony make the horizon appear. A second guitar line might have modernized the record in ’63, but the choice not to crowd the midrange is why it feels timeless now.

Two micro-stories, vivid in my mind:

A late-night taxi ride through a city I barely knew, rain on the windshield like Morse code, the driver humming along to a local radio segment of “songs you grew up with.” He turned it up, said nothing, and the silence between us felt like understanding.

A hospital corridor a few years ago, volunteers pushing a small cart with a speaker—someone’s idea of bringing music to the ward. A nurse, exhausted, mouthed along as she walked. Nothing performative. Just a line learned young, retrieved when needed.

And yes, back to Anfield: a match I watched on television, the camera cutting to faces in the stand as the chorus rolled out. What struck me wasn’t spectacle; it was the ordinary faces—parents, kids, people in heavy coats—each using the melody for something personal while making one sound together.

It’s also instructive to compare versions. Patti LaBelle & The Bluebelles give it spectral force; Elvis lets his gospel choir carry the burden; later pop arrangements drape the tune in contemporary sheen. Gerry & The Pacemakers? They find the exact point where pop meets prayer. That’s why the recording outlasts fashion. Its studio craft is midcentury, but its sensibility is sturdy, almost folk-like—a melody to be borrowed and given back.

For listeners coming to the song fresh, a recommendation: try it once on modest speakers in a small room, then again on a system with more air around the treble. You don’t need premium gear to get the message, but on a decent home audio setup the strings bloom and the vocal sits in space the way it would in a hall. You begin to hear the arrangement as architecture, not just ornament.

Because this is a review, a few final particulars for context. The single was issued in 1963, hit UK No. 1, and appears on the debut LP How Do You Like It?—a meaningful placement that underlines its role in the band’s first flush of success. George Martin’s production stewardship during this era is part of the reason the record rings with clarity and humility rather than bombast. And while the label credits and catalog numbers fascinate discographers, what matters for most of us is that the track endures not only as a chart entry but as a shared rite.

One last note on language. We sometimes call songs “anthems” too easily. An anthem, properly, is sung by many for a reason beyond entertainment. This recording made that leap. It teaches courage not as a solo performance but as something we borrow from each other. That’s the genius: a pop single that knows when to step aside and let the crowd sing.

As I switch the lamp off and the last chord fades, I’m left with the simplest measure of a classic: it doesn’t require the moment to be grand to feel grand; it makes room for whatever you’re carrying and walks beside you until you can carry it yourself.

Listening Recommendations

The Beatles – “The Long and Winding Road”

Similar orchestral ballast and late-era tenderness; a string-laden slow build that treats vulnerability as strength.

The Hollies – “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother”

Another communal-leaning ballad where restrained vocal delivery meets resolute moral center.

The Righteous Brothers – “Unchained Melody”

Dramatic but disciplined, with soaring vocal phrasing that turns personal longing into public catharsis.

Elvis Presley – “You’ll Never Walk Alone” (1967)

A gospel-framed rendition showing how choir and lead can refract the same melody into devotion.

Gerry & The Pacemakers – “Ferry Cross the Mersey”

The band’s own elegiac pop, Liverpool again as place and metaphor, strings used as supportive weather.

Roy Orbison – “Crying”

A lesson in emotional architecture: voice as cathedral, arrangement as scaffolding for release.

Notes and sources: The single’s UK chart-topping status and label are documented by the Official Charts Company; the song’s Rodgers & Hammerstein origin and 1963 success are summarized in standard references; Liverpool’s adoption and the track’s presence on How Do You Like It? are widely reported and supported by reliable discographies.

(For clarity: 1963 UK No. 1 single on Columbia/EMI; appears on the 1963 album How Do You Like It?; early recordings produced under George Martin’s direction; later civic life intertwined with Liverpool F.C.)