The tape hiss is the first thing I imagine when I press play in my mind: a soft veil, then the room brightens as the band drifts in—strings like light spilling across a polished floor, tambourine catching the cast-off sun. The opening cadence is neither rushed nor languid; it’s a steady hand guiding you to the center of the melody. Peter Noone’s voice arrives with that youthful clarity, unfussy and melodic, slightly smiling at the edges, as if the microphone itself has encouraged him to lean closer. It’s a pop moment you feel in the chest before you parse a single word.

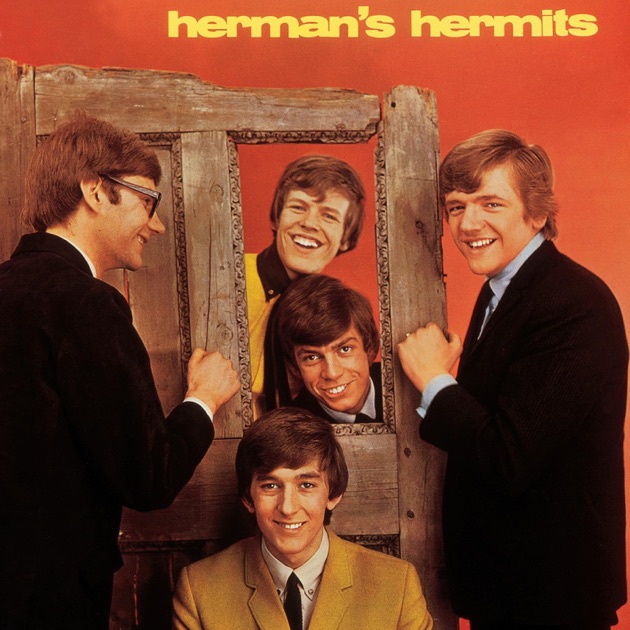

By 1967, Herman’s Hermits were fixtures of British Invasion radio, a group whose genial image belied the tight craftsmanship behind their records. “There’s a Kind of Hush,” produced by Mickie Most, materialized in that hinge-year when psychedelic experimentation crowded the charts, yet here was a record that refused the lysergic swirl for something more direct. Released on the band’s home turf under EMI’s Columbia imprint and stateside through MGM, it was positioned as both a single and the namesake of a U.S. LP—one of those cross-Atlantic packaging quirks that marked the era. The song proved its mettle quickly, rising into the top tiers in multiple markets and giving the group another international calling card.

Context matters with Herman’s Hermits because their timeline tells a story of immaculate singles. They were never an “albums band” in the way of their peers, but they were masters of three minutes. The team—Most at the controls, the session-first approach, the emphasis on strong material—understood radio like a native language. “There’s a Kind of Hush,” written by Geoff Stephens and Les Reed, fits squarely into that philosophy: a melody that feels familiar on first contact and inevitable by the second chorus, a lyric that collapses a small romantic revelation into a communal hush. The band doesn’t strain for grandeur; they place every accent exactly where it belongs.

Listen to the arrangement and you’ll hear layers that feel nearly transparent. Clean rhythm section first: a lightly pulsing bass, brushed or delicately struck drums, a tambourine that sparkles without crowding the beat. Above it, a cushion of strings glides in measured arcs—no overwrought drama, just a gentle lift on the chorus and a softer landing on the verses. Woodwinds—likely flutes—trace a halo around certain phrases, offering air and a hint of pastoral sweetness. In the midrange, the acoustic strum is tidy, and a chiming counter-line arrives like a polite greeting. The mix keeps the vocal front and center, not in a spotlight that blinds, but in a glow that flatters.

The harmonic language is reassuring, the kind of diatonic staircase you can walk up with your eyes closed. Still, there are small surprises. A pivot chord slips you into the chorus with more grace than you anticipate, and the backing voices rise together in a cushion that never quite breaks into the bombast you might expect from late-60s pop. It’s restraint as a guiding principle. The song courts sweetness and gets it, but refuses stickiness. Even at its most sentimental, there’s a steadiness in the tempo and a respect for space.

What catches me—the detail that often lodges in memory—is the balance between private and public feeling. The lyric imagines a world where everything quiets because two people have discovered a moment that eclipses the noise. On record, that conceit becomes an engineering choice. The high end is polished, but not brittle. Reverb is present, yet short—enough to imply a room, not a cathedral. Noone’s consonants have definition; his vowels are rounded but not syrupy. You can trace the reverb tail on the vocal as it taps the back wall and falls away, and in that tiny arc the song’s premise lives: the world hushes, the air carries only what matters.

Of course, the aesthetic was shaped by the band’s overall direction in this period. Most had a knack for simplicity rendered as sheen, for taking a straightforward chord map and turning it into a postcard from what pop could be at its most welcoming. There’s no studio showboating here, no reverbed timpani, no carnival of sound effects, just pieces assembled with patient confidence. And so the record sits comfortably next to other Hermits favorites from the mid-decade, while also sounding a touch more grown, a touch more reflective. The group that once winked through novelty and nursery-rhyme proximity now offers a small, sincere pledge.

If the 1967 context tempts you to draw psychedelic parallels, resist the urge to force it. This is not sunshine pop gone kaleidoscopic; it’s more like a well-pressed dress shirt caught in late-afternoon light. The glamour is the finish. The grit is the discipline. And that contrast is a key part of its appeal. By standing apart from the countercultural storm, the song became an alternative to it—a reminder that euphoria can be found not only in expanded consciousness but also in tuned harmony and careful phrasing.

There’s also a tactile sense of room. Close your eyes and you’ll hear the soft press of fingers on strings, the slightly delayed entrance of a background vocal on a breath that wasn’t perfectly aligned but was perfectly human. The rhythm section doesn’t push; it smiles. Dynamics are modest yet deliberate. Verses sit half a notch lower; the chorus opens like curtains pulled back an extra hand’s width. If you’re listening on good speakers, a subtle low-mid warmth cushions the entire performance, suggesting a recording chain that prized clarity over conquest.

I like to think of “There’s a Kind of Hush” as the rare piece of music that lets everyday life overhear a secret without betraying it. The singer never shouts. He welcomes you to overhear the whisper. That emotional posture makes the record unusually durable. It doesn’t chase your attention; it earns it.

One micro-story: I remember an evening train pulling out of a small station, windows fogging as bodies settled in after a winter day. A student across the aisle scrolled through a playlist of new releases—dense, modern, all teeth and neon—before stopping on this track. The coach seemed to exhale. No one looked up, but the atmosphere shifted slightly, like a theater when the house lights dim. Nothing dramatic. Just ease.

Another: A backyard wedding where the couple forwent an elaborate processional for a discreet entrance through a side gate. The DJ, perhaps sensing the mood, slid this song into the cocktail hour set. Parents, aunts, older cousins—people who had lived through the original chart run—smiled with a recognition that needed no words. A few heads tilted, some hands found each other. The track was nostalgia, yes, but it also functioned as new air in that space.

A third: A late-night drive in spring rain, wipers tracing a slow metronome. The track came on the radio, the kind of terrestrial playlist where 60s hits thread between classic rock and soft 70s. The car cabin turned into a gentle chamber. Each ride cymbal tick sounded like a raindrop meeting glass and staying. By the time the final chorus came through, the city around me felt slightly polished, as if the night had been waxed.

If you want to interrogate the performance further, pay attention to timbre. Noone’s lead is light-grain oak, not mahogany—pleasantly pale, smooth, strong enough to hold weight without darkening the mood. The backing vocals are brushed chrome: reflective but not dazzling. The strings are satin rather than velvet; the edges are rounded, the body is full, and the tone never turns cloying. When the melody lifts, the arrangement lifts with it—not by adding mass, but by opening small windows in the texture.

I’ve heard listeners describe the record as “lightweight,” a critique often aimed at mid-decade British pop that resisted the heavier themes emerging from peers. Yet writing light without turning flimsy is harder than it looks. The song’s craft lies in selective emphasis. Every element earns its keep. No grand guitar solo arrives to claim center; no orchestral swell insists on its own applause. Instead, details serve proportion. Even the bridge—so often a place for melodramatic escalation—chooses poise.

As for instruments that ground the track, the acoustic figures do steady work, and a softly voiced keyboard line rounds the body. Whether it’s a compact upright or electric key, the presence is there, embellishing without demanding. No showy comping, just supportive voicings that trace the chords and leave room for breath. In a modern listening setup, you can especially appreciate these balances. Cue it up on decent gear and the song’s spatial order snaps into focus, the kind of subtlety that rewards careful listening through studio headphones.

Place the song in the band’s broader arc and a pattern emerges. Herman’s Hermits were adept at finding songs that suited Noone’s youthful poise, then finishing them with a gloss that read cleanly across AM dials everywhere. “There’s a Kind of Hush” appears just as pop was splitting into more specialized lanes—heavy, baroque, psychedelic, folk-rock—and it plants its flag in the pop-literate middle. You could hear it after a Motown single and before a jangly West Coast track and not feel jarred. That universality helped it travel, and it still travels now, folded into playlists and wedding mixes with the ease of something that knows how to leave space for other moments.

Many sources note that the track performed strongly on both sides of the Atlantic. You don’t need exact chart numbers to hear why. The hook is simple but not simplistic; the lyric trades in shared weather rather than ornate metaphor; and the recording invites you to lean in rather than step back. It’s an inclusive design: personal enough for the headphone listener, open enough for a café sound system, tidy enough for radio stacking.

This is also a quietly instructive record for musicians and producers. If you were to glance at the chord chart—think of it like skimming the sheet music before a rehearsal—you’d see how unassuming the architecture is. The drama lives in arrangement choices and performance decisions: vibrato kept spare, phrase endings slightly tapered, percussion tucked into the pocket with a smile rather than a smirk. An engineer could point to the frequency spectrum and show you how little of it is wasted. The lesson isn’t minimalism as ideology; it’s intentionality as craft.

“By standing still and shining clearly, the record proves that quiet can be a form of confidence.”

I often picture the session scene in practical terms: a singer with an ear for melodic line, players who understand that timing and tone needn’t be flashy to be memorable, and a producer whose instincts tilt toward accessibility without condescension. That team made a record that wears formality lightly. It’s easy to overlook pop this tidy because it doesn’t insist on interpretive effort, yet its steadiness is part of why it endures.

A quick note on the band’s image in this period: the Hermits were sometimes cast as clean-cut pop foils to grittier contemporaries. That’s a convenient narrative, but it understates the skill involved in landing simplicity so consistently. The charm here isn’t an accident; it’s a chosen result. And in 1967, when the surrounding landscape grew wilder by the month, that choice reads as clarity rather than caution.

If you drag the fader down to the individual components, you can admire how they stack. The rhythm guitar strokes are clipped and confident, providing lift without flashy syncopation. A modest line or two snakes between vocal phrases, a melodic aside that never competes. Farther back, a keyboard presence—likely a compact acoustic voice rather than a grand—adds roundness to the harmony and a suggestion of room. You may even catch a small breath before a backing-vocal entrance, a humanizing tick that a modern comp might smooth away. Those choices keep the song alive rather than lacquered.

The best way to appreciate the record now is to listen through a contemporary lens. You can hear how carefully it was designed to sound good on any system—transistor radios, car dashboards, living-room consoles. That adaptability remains its secret strength in a world where playback environments vary from phone speakers to elaborate home setups. Even on modest gear, the vocal line sits where it should; on better systems, the low end rounds out and the upper strings shimmer. If you’ve been considering a small upgrade to your home listening chain, this track is an unexpectedly strong test for balance, particularly in the upper mids.

And then there’s the emotional use-case: moments that benefit from a tone of invitation. It’s a track you can play when conversation matters, when you want music to lean in with you rather than push against you. At gatherings, it’s a gentle bridge between generations, partly because its sentiment is so unguarded. No ironic posture, no tricky allegory—just warmth.

In the end, “There’s a Kind of Hush” occupies a precise niche in the Herman’s Hermits catalog: a marker of maturity without any loss of ease. It’s also a postcard from a moment when pop polished itself for the widest room and still kept a human pulse. If your taste usually runs heavier, the song may feel like a feather. But a feather can be a small engine if it’s placed in moving air. This one still lifts.

As the track fades—voices thinning, strings settling—you may find you’ve leaned closer to the speakers than you intended. That’s the quiet spell it casts. Not hypnosis, just attention. And the invitation still stands: close the door, reduce the light, and let that hush arrive again. It’s a modest request for a modest reward, which is often how love communicates best.

Before you revisit it, a practical aside: if you’re sharing it with a young musician learning harmony, point out how the backing lines support the lead without stealing focus—a miniature lesson you could tuck into early guitar lessons or ensemble work. For listeners, it’s enough to notice how the song lets a smile travel from phrase to phrase.

The last detail is almost incidental but true: the record is easy to keep close. Play it once, and the chorus will wake you the next morning, soft as daylight.

Recommendations for listening? Turn it up just enough that the room dims. Then listen for the moment the strings enter and the tambourine flickers. That’s where the hush begins.

Listening Recommendations

-

The Association – “Windy” (1967): Sunlit harmonies and crisp orchestration evoke the same bright, buoyant optimism.

-

The Hollies – “Bus Stop” (1966): Tight melodic writing and polished production carry a bittersweet pop storytelling edge.

-

The Turtles – “Happy Together” (1967): A soaring chorus and clean arrangement that balance romance with radio-ready clarity.

-

Petula Clark – “I Couldn’t Live Without Your Love” (1966): Sophisticated London pop sheen with a tender vocal centerpiece.

-

The Zombies – “I Want Her, She Wants Me” (1968): Baroque-tinged craft and measured sweetness, ideal for harmony lovers.

-

Gerry & The Pacemakers – “Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying” (1964): Orchestral restraint and a graceful vocal line for gently reflective moods.