In the mid-1970s, Merle Haggard was at the height of his fame, yet behind the curtain, he often felt the weight of life’s disappointments. One night after a show, he found himself alone in a quiet motel room, watching an old black-and-white movie on TV. The screen was filled with perfect romances and happy endings, a stark contrast to the reality he’d lived — failed marriages, long stretches on the road, and the loneliness that came with it. He realized how often people believe life should play out like the movies, only to be met with heartbreak when it doesn’t. That moment inspired “It’s All In The Movies” — a bittersweet reminder that the silver screen’s promises are just illusions. For Merle, it was both a confession and a comfort, a way to tell fans: life isn’t perfect, but the stories still matter.

The first time I felt “It’s All in the Movies” land, it was late—one of those road-trip nights when station IDs blur and the sky over the interstate looks like a blank reel waiting for pictures. A familiar voice rose out of a low noise floor, steady as an engine. Then came the strings and that unhurried, river-sure cadence. By the second verse, the headlights were the only stars I needed. Merle Haggard was telling a love story about illusions, and paradoxically, it never felt more real.

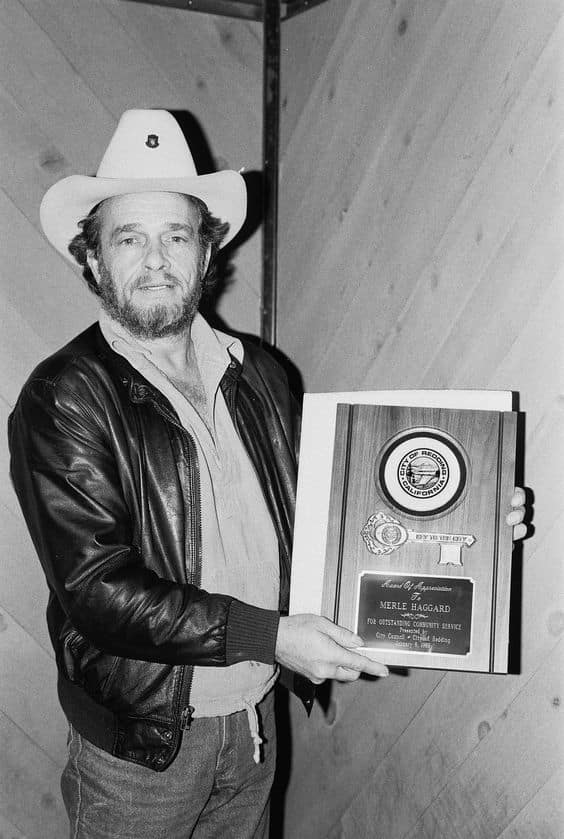

By 1975, Haggard had already staked out a vast frontier inside American country music. On Capitol Records through the mid-’70s, he’d balanced workin’-man grit with a poet’s sense of proportion—always exact, never ornate for its own sake. “It’s All in the Movies,” the title track from the album of the same name, arrived in that phase of late-Capitol maturity. It was produced by longtime collaborator Ken Nelson, with many sources also noting the guiding presence of Fuzzy Owen—two figures who had helped shape Haggard’s lean, unflashy approach for years. The record quickly rose to the top of the country charts in late 1975, the kind of success that feels inevitable only after it happens.

If you place it alongside earlier Haggard triumphs—restless, steel-forward statements like “Mama Tried” or “Sing Me Back Home”—this piece of music seems almost upholstered. Not overstuffed, but upholstered: strings that breathe, background vocals that cradle the line, and a rhythmic bed that moves like a confident actor crossing a stage. Haggard and his band, The Strangers, had nothing to prove by then, so they proved nothing and everything—playing at a volume and tempo that allowed nuance to do the heavy lifting.

The arrangement opens with an easy sway. There’s a hush to the initial downbeat—as if the room itself is leaning in. You hear a brushed drum pattern laying down a soft grid; then the bass slides under it, positive and unhurried. A light acoustic figure introduces the harmonic palette, and before you realize it, the strings have joined—not as ornamental tinsel but as genuine partners in the storytelling. The reverb tail here is short, intimate, the kind that locates musicians a few feet in front of you rather than in some cavernous hall. The attack on the snare is sanded down, while the sustain on the strings is just long enough to feel like breath.

Haggard’s vocal sits at the center, dry and unwavering. He doesn’t push to the rafters; he narrows the aperture and lets the lines gather heat from his phrasing. Listen to how he leans into vowels, how consonants arrive a hair late and yet exactly on time. The vibrato is minimal, almost conversational. He gives the words moral weight by refusing to underline them. In that restraint lies the spell.

What the song says is simple: people chase dreams that glow brightest onscreen, yet daily life, even with its disappointments, can be its own premiere. The lyric imagines romantic fulfilment as a film that can be spliced, rewritten, forgiven. “It’s all in the movies,” he tells us—both a shrug and a benediction. The gesture is archetypal Haggard: skeptical of sheen, tender toward the people who fall for it, and clear-eyed about the cost. You could call it realism, but in his hands realism flowers into mercy.

Instrumentation-wise, this recording is full of tiny balances. The rhythm section never puffs itself up; it moves like a shadow behind the melody. Electric guitar decorates only in minimal filigree—low in the faders, answering phrases instead of interrupting them. A soft piano figure appears as if through a half-open door, laying simple triads that suggest resolve without declaring it. The strings swell and recede with a patience that feels earned. There’s even a sense—especially in the middle eight—of the violins gently threading the melody so that Haggard can float across, as if the band is building a land bridge under his feet.

This is not a grand “Nashville Sound” pastiche, though. It is tidy without being precious. The Strangers had always managed a feat most bands never do: appearing to do less while doing more. Their gift is the negative space, how they frame Haggard so each word lands. Ken Nelson’s production respects that ethos; nothing is over-roomed or lacquered. The stereo image feels honest—acoustic left of center, a mellow electric complement on the right, strings rising in a kind of soft halo around the vocal. If you’re listening on decent studio headphones, the blend reveals its seams not as flaws but as hand-stitching.

Some listeners remember where they were when they first heard the hook. For me it was that night highway. For others, the song might have arrived across a kitchen radio at the end of a long shift, when coffee tastes like cardboard and laughter starts sounding like a choice. Haggard’s narrator doesn’t scold the person who believes in cinematic endings; he just names the price of keeping the projector running. He champions the stubborn hope that love can be edited toward better outcomes, even if reel changes leave scratches.

Consider the dynamic curve. Verses keep their powder dry; choruses let a bit more air into the room. There’s no big modulation, no horn section, no dramatic ritard that tells you how to feel. The emotional lift happens in increments—an extra bar of sustain under the strings, a slightly more forward harmony line, a bass note that hangs an extra breath. It communicates like a good actor who knows that whispering into a microphone can be louder than a shout.

Haggard’s legacy often gets framed as “tradition keeper” vs. “outlaw traveler,” but the truth is more interesting. He was a formalist who trusted the form enough to be tender with it, and this track is a late-Capitol case study. The veneer—those strings, those tidy backing vocals—let him smuggle in skepticism and compassion. Glamour versus grit? He turns the binary into a conversation. The glamour is the string sheen; the grit is the way he refuses to moralize. The song recognizes the thrill of the spotlight and the long quiet afterward—and it does so without bitterness.

Here’s the line that keeps echoing: the chorus’s reassurance that “it’s all in the movies” doesn’t dismiss human longing; it reframes it. If love is a kind of cinema, then faithfulness is the editing room—a craft that happens offstage, with choices, trims, second takes, and patient revisions. That’s why the last chorus feels less like an anthem than a gentle curtain. We’re not promised perfection. We’re offered another draft.

“Illusions aren’t the enemy here; they’re the raw footage—we discover our truth in what we choose to leave in.”

A few historical bearings matter. The song’s 1975 release marked a period when country radio was increasingly open to lush textures and crossover melodies, even as certain corners of the audience bristled at anything that smelled like compromise. Haggard’s cut threads the needle. It sits comfortably on playlists that favored smoother timbres while maintaining his core identity. You can hear why it became a staple. It’s accessible without flattery, refined without faintness of heart.

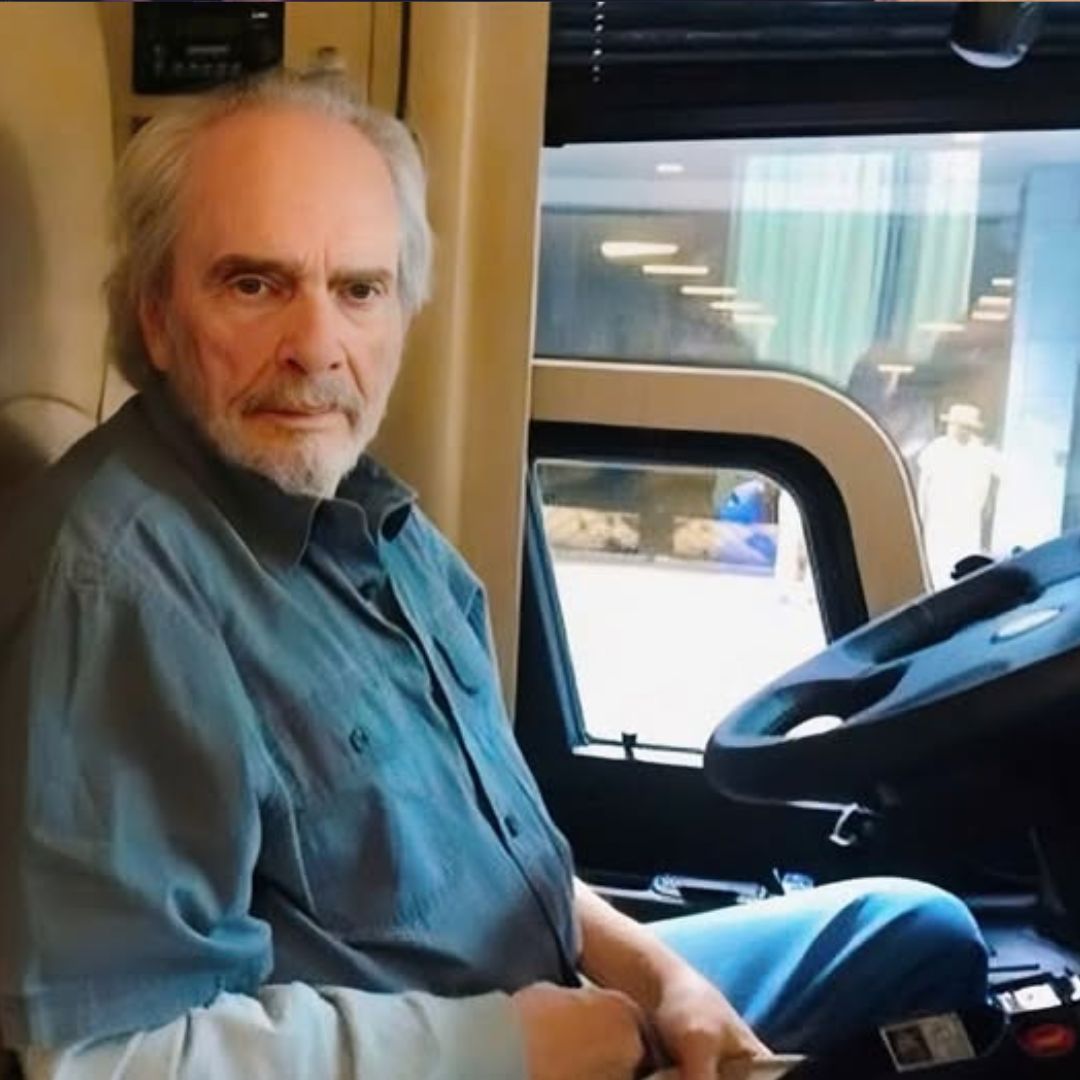

Put this track up against the broader arc of his work and it reads like a bridge. From the Bakersfield sting of earlier records toward the more polished material that would follow as he moved labels later in the decade, this number gathers his strengths into a single, generous frame: observational wisdom, a voice that refuses melodrama, and arrangements that speak in complete sentences. It’s not the swaggering Haggard of myth nor the bare confessor; it is the adult writer, watching, taking notes, and offering them back with grace.

There is a tactile quality to the soundstage. The brushes graze the snare with a papery hush; the bass is round, almost without edge, yet present. The acoustic strums are short and percussive, while the electric lines are soft beams of light. The strings never bloom beyond the borders—no sudden cinematic walls—but they give the choruses a mild lift, like a window shade raised an inch to invite morning in. All of this contributes to the illusion at the heart of the lyric: the ordinary made luminous, the living room recast as a theater.

Micro-story one: a friend once told me this was his “closing time” song when bartending in a small town on the edge of a dry county. He’d play it as the neon was switched off, and couples who had argued all night would soften on their way to the door. Not reconciled, not transformed—softened. He said it was because the song didn’t pick a side; it picked the possibility of next time.

Micro-story two: years later, at a backyard cookout, a cousin set this track between more contemporary Americana cuts. The younger crowd, unfamiliar with Haggard beyond a name on a T-shirt, stopped talking by the second verse. Someone asked what year it was from; someone else said the strings made it feel like a deluxe remaster of their own worries. The song sat there, patient, and did its work.

Micro-story three: a record collector I know swears by the original vinyl pressing as the best way to encounter the recording’s grain. He’s not chasing nostalgia; he insists the midrange details—the little breaths around the vocal—just sit better. I don’t evangelize for format, but I understand the urge. When a track is this poised, you want to meet it on its terms. If your music streaming subscription is your primary conduit, no shame; the emotion makes it through either way.

There’s a sly elegance in how the lyric refuses to solve the dilemma. Are we better off with a myth that keeps us trying, or with realism that accepts the limits of our editing room? The song doesn’t police the answer. It gives you a hallway lined with movie posters and asks which door you’ll open. Haggard’s delivery implies he’s tried most of them and found rooms worth returning to. That, more than any moral, is the wisdom I hear.

And so it endures. Not as the most quoted, not as the most covered, but as a faithful companion for those moments when you realize life rarely matches its trailers. It tells you that this is okay. That the dull ache of an honest day might redeem the shaky cut. That promises sometimes need reshoots. The takeaway is gentle and clear: the camera rolls whether you’re ready or not, but you still get to choose your edit.

If you’ve only known Haggard by his rougher, bar-band edges, try this like a slow sip. Hear how the arrangement respects the lyric; how the vocal honors the audience; how the band builds a frame that flatters without lying. It’s the kind of craftsmanship that vanishes into the experience. And it’s the sort of song that, once it’s with you, tends to show up again—closing a night, steadying a hand, reminding you that the reel keeps turning, even when the credits seem to roll.

Finally, it’s worth noting how this track models a particular kind of country wisdom that remains scarce: clear-eyed without cruelty, hopeful without denial. It neither worships the screen nor laughs at those who do. It affirms that we move through the world like actors, yes, but also like editors. We revise. We try again. We leave some scenes on the floor. When the last chord settles, what you’re left with is not a grand message but a calm one—room to breathe and, maybe, to pick a kinder cut next time.

Recommendations rarely feel right at the end of a song like this, but this one invites them, because its spirit is generous: it says, here are some other rooms where the lights are kind and the stories know your name.

Listening Recommendations

-

Merle Haggard – “If We Make It Through December” — Another gentle, grown-up reckoning, trading string sheen for winter air and quiet resolve.

-

Merle Haggard – “Silver Wings” — A graceful glide of melody and memory, pared back to essentials so the ache can travel.

-

George Jones – “A Picture of Me (Without You)” — Lush arrangement in service of emotional clarity, from a voice that lives in the small turns.

-

Charlie Rich – “The Most Beautiful Girl” — Early-’70s polish that still leaves room for human grain, proof that pop crossover can carry depth.

-

Glen Campbell – “Rhinestone Cowboy” — Cinematic shimmer meets workaday longing, a bright marquee with honest letters underneath.

-

Willie Nelson – “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” — Radical simplicity that lets time do the speaking; every note earns its place.