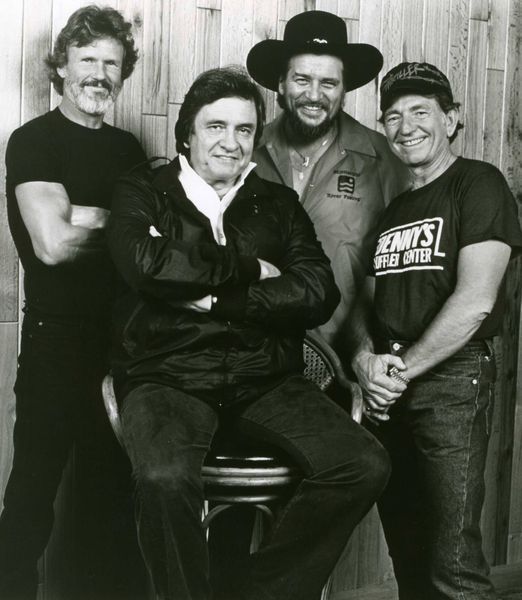

It wasn’t just a band; it was a collision of four separate universes on a single stage at the Nassau Coliseum in 1990. You had Willie Nelson’s easygoing charm, Waylon Jennings’ raw grit, Johnny Cash’s thunderous gravity, and Kris Kristofferson’s poetic soul all pouring into one microphone for “Luckenbach, Texas.” Each man was a legend in his own right, carrying his own history and scars, yet for a few minutes, they created something impossibly rare: a perfect “harmony without ego.” This wasn’t a performance that could be rehearsed; it had to be lived, a moment where four outlaws stood together and turned a simple song about a small Texas town into a powerful anthem of unity for everyone to share.

The camera finds faces before it finds the stage—cowboy hats, denim jackets, that slow Long Island sway that sets in when a crowd senses it’s about to be sung into the same story. Then a cheer lifts like a gust through an open barn door. A familiar shuffle, a small count, and “Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love)” ambles into the room as if it has personally shaken every hand there. The Highwaymen—Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, and Johnny Cash—don’t so much “start” the number as let it bloom. What in 1977 felt like a wry escape plan for a weary couple now arrives in 1990 as a shared memory made public, an outlaw benediction performed by four artists who know exactly how much warmth one song can carry across an arena.

This live take comes from their Nassau Coliseum concert on March 14, 1990, later compiled and released as Live – American Outlaws, a Legacy Recordings set that opened a vault of footage and audio when it landed in 2016. The anthology places “Luckenbach, Texas” deep in the night’s second wind—right where a familiar chorus can turn strangers into a choir. The package documents that tour’s full-blooded chemistry and confirms how effortlessly these four could fold individual catalogs into a single traveling conversation.

Of course, “Luckenbach, Texas” didn’t start as a Highwaymen number. It was Waylon’s, released in April 1977 as the lead single from Ol’ Waylon, written by Chips Moman and Bobby Emmons and produced by Moman. RCA put it out, radio grabbed it, and the song climbed straight to the top of the country charts. It was a winking invitation to step away from shiny burdens and head toward a simpler promise, one that even Willie Nelson punctuated on the original recording with a friendly vocal cameo. That provenance matters here, because when Willie sidles up to the microphone in the Nassau footage, his presence feels less like a guest turn than the completion of a long-running conversation that began on the original cut.

Listening to the Highwaymen version, you can hear how the arrangement keeps the bones of the studio hit but loosens the joints. The tempo has a walkabout gait—unhurried, confident. The rhythm section keeps a gentle two-step, bass breathing in warm quarter notes and drums brushing the backbeat just enough to suggest motion without urgency. Above that, acoustic strums hang like porch light, while an electric lead slips small curls between phrases, never crowding the vocal. A taste of steel floats over the verses, more halo than spotlight, and the crowd’s applause forms its own reverb chamber, a soft, shifting room tone that the singers play against.

What I love is how the voices handle time. Waylon sings like a barstool philosopher who’s learned not to oversell the moral; he leans on the second syllable of “basics,” letting the vowel relax, almost a smile. Willie’s phrasing remains elastic—he leans across lines, lands a half-step behind the beat, then stitches the phrase back into place with that nasal, effortlessly conversational timbre. Kristofferson’s lower register adds a smoked oak texture; Cash drops in like a gate swinging open, the timbre alone rewriting the room’s dimensions. It’s democratic without being bland, and it’s loose without losing shape.

The camera direction—simple, generous, unflashy—helps you notice the physical rhythms that make the chemistry legible. Waylon plants and pivots; Willie bends slightly at the waist on sustained notes; Kristofferson’s shoulders ride the groove like a metronome whose purpose is to reassure; Cash stands nearly still, and the stillness works like a visual bassline. The kindness of their cues to one another—nods, glances, a grin when a line lands—tells you how a traveling show becomes a band rather than an anthology.

Some live recordings hem songs in with arena echo; this one turns space into an instrument. You can hear the air between the drum hits. You can hear the crowd settle after each chorus, the murmurs that sound like a thousand contented exhalations. The mix keeps the front voices prominent but allows the guitars to sketch the tune’s architecture, right down to those slight swells that cushion the last line of each verse. The result is a performance that keeps its shoulders loose; even the applause seems to arrive in time.

There’s a temptation to turn “Luckenbach, Texas” into a totem of nostalgia, a kind of souvenir stand on the highway between memory and myth. But what the Highwaymen do here is subtler. They keep its rope swing intact—yes, the chorus still feels like leaning back over a creek you know—but they also remind us the song began as a pragmatic suggestion. Get small. Go back to what matters. In a year when country music’s commercial apparatus was loudly expanding, these four legends offered a counterpoint: expansion is fine, but not at the expense of intimacy. The performance, in that sense, is philosophy disguised as a singalong.

Context sharpens that point. Back in ’77, Ol’ Waylon marked an apex of Jennings’ outlaw era—commercial power with creative control, and the muscle of a hit single that would haunt set lists for decades. Chips Moman’s role is crucial: an R&B and pop-savvy architect who helped Waylon frame a country tune with crossover intuition. On paper, that pairing reads like collision; on tape, it tracks as chemistry. And it’s no coincidence that Moman co-wrote the song—its efficient structure, its earworm syllables, its sly references to Hank and high society—bear the stamp of a writer-producer who believes in hooks as acts of mercy.

One detail that always registers for me in the Nassau performance is the way the band leaves room around the verses, as if keeping chairs open for each singer’s history. When Waylon’s turn comes, you hear the authority of authorship—not literally, since he didn’t write it, but spiritually, because he was the first to give it a home. When Willie sings, that original cameo becomes a full embrace, a reminder that the tune’s DNA always carried his name. When Cash and Kristofferson roll through, the lyric’s invitation broadens: this isn’t just about a couple’s course correction, but about any listener who has felt cost outpace value. “Back to the basics of love” becomes a floating refrain for grown-ups who’ve tried glamor and found it too heavy to lift.

There’s humor in the performance too, a stingless kind that outlaws can get away with because it’s grounded in affection. You catch it in the timing of a look, in a dip of the head after a well-landed reference, in Willie’s almost conspiratorial half-smile when he touches a line he’s sung a thousand times and finds a fresh corner to round. That levity keeps the song from becoming self-righteous. It’s not a lecture; it’s a hand offered to anyone who’s ready to climb out of a hole they accidentally dug with success.

If you close your eyes during the instrumental break, the tones tell a story about touch. The lead player favors a round attack, notes blooming instead of biting. The steel’s vibrato feels more like a human breath than a machine effect. Behind them, the keys place small, sustained pads that lift the harmony like a friendly palm to the lower back. Nothing is showy—no audacious runs, no studio tricks smuggled on stage. Just taste, proportion, and time felt from the knees up.

“Luckenbach, Texas” is also a test of diction and dynamics, and the Highwaymen pass without drawing attention to the grade. Phrases sit where they belong; the chorus steps forward half a decibel; the final refrain acquires a hint of rubato phrasing that signals goodnight without saying the word. It’s a singer’s arrangement, high on legibility, low on ornament.

Place the moment within the larger arc of the supergroup, and a different picture emerges. The Highwaymen began as a star alignment—four pillars of country sharing buses and songs—and could have coasted on reputation. Yet the Nassau document reveals something sturdier: a working unit that rethinks familiar material without violating its essence. There’s a reason the 2016 release felt like a revelation to fans who knew the myth but hadn’t heard this night in full. The tapes didn’t give us a new story so much as restore a key chapter we’d only read in summary.

Because the original hit is so bound up with the late-’70s outlaw wave, a few production facts matter. The studio “Luckenbach” came out under RCA in 1977, with Moman’s name listed as producer and co-writer, and Bobby Emmons as the other pen—a pairing that explains the song’s economy and its slyly soulful pocket, an economy the Nassau band preserves by underplaying even the fun parts. If the track were any tidier, it would feel laminated. Fortunately, these players prefer wood grain.

There’s a listening vignette that returns to me when I watch this performance. I’m in a kitchen at midnight, the city asleep, nursing lukewarm coffee. A friend texts a link and a single line: “Let this take five minutes off your shoulders.” I tap play. The first chorus arrives, and I feel the room widen. It isn’t nostalgia; it’s permission—to step back from the spreadsheet logic of a life and sit for three minutes with something that knows how to breathe.

Another: a used-CD shop in a college town, the kind with hand-written dividers and a clerk who recommends titles with the precision of a pharmacist. A copy of Ol’ Waylon is propped at eye level. A kid in a faded band tee holds it like a relic. I hear him ask if this is the one with “Luckenbach.” The clerk nods, and the kid’s eyebrows rise as if he’s just been told where the river crosses itself. Years later, when he stumbles on the Highwaymen video, he’ll recognize the outline but marvel at the way four voices can change the color of a tune without changing its shape.

A third: a dad fixes a porch step with his teenager, the summer heat already into triple digits. The radio station fades between driveway ads and honky-tonk memories, and then there it is—“back to the basics of love.” The kid doesn’t know the references; the dad knows them too well. Both hum the last chorus, and for a moment the distance between them feels measurable and, more important, crossable.

If you want to hear the Nassau performance’s small pleasures in relief—the pick noise before a downstroke, the vocal air just before consonants—I’d suggest a quiet room and good playback. The transient detail that pops when you use proper studio headphones can make the ensemble’s restraint glow. Yet the piece is forgiving; it translates just fine on living room speakers while you make dinner or step outside to watch the sky darken. The song’s bureau of essentials remains open for business either way.

Here’s the paradox that keeps me replaying it: the more famous the performers, the more invisible their best work often becomes. “Luckenbach, Texas” is friendly enough to soundtrack a grocery aisle, robust enough to headline a festival, and familiar enough to feel pre-owned by its listeners. But in the Highwaymen’s 1990 hands, it also becomes a modest act of care. They don’t punch it up; they hold it up. And the crowd recognizes the gesture.

“Four giants don’t enlarge the song; they merely lift it high enough for everyone to see their own reflection in it.”

As a critic who tends to chase the new, I find it humbling when a performance like this refuses to age into mere memorabilia. The lyric’s premise—choose simplicity, at least in your heart—hasn’t lost a step. Maybe that’s why the applause in the final seconds sounds less like celebration than assent. We know what’s being asked of us. We also know it isn’t easy. But for three or four minutes, with those voices and that steadied groove, you can believe that getting back to the basics is not retreat but return.

Finally, a word about placement in the careers onstage. Waylon, by 1990, had already proven himself an architect of ’70s country’s rebellious middle—hits, authority, and a sense of humor about both. Willie was a national treasure who could tease a melody until it confessed, while Cash had transformed American gravity into baritone. Kristofferson, the poetic pragmatist, rounded the quartet with the songwriter’s instinct to cut to the bone. No one cedes identity here; no one grandstands, either. That balance—rare as a red moon—is what makes the performance feel more like a living room with 16,000 chairs than a superstar revue.

I’ve tried to avoid sanctifying the moment. The truth is simpler, and better: four men who know the road, playing a song that knows them back. If you haven’t revisited this rendition in a while, carve out space for it. It won’t fix anything. It will make room around what needs fixing. And when the last chord fades, you may feel, briefly and gratefully, that the basics of love are not a destination but a direction.