The year is 1968. The airwaves are thick with psychedelia’s kaleidoscopic dreams and the hardening grit of rock, yet a specific kind of operatic pop perfection still held sway. You’re driving late at night, radio dial glowing a faint, nostalgic amber, when a sound cuts through the static. It is a voice, trembling and rushed, almost breathless with a terrible urgency.

“The Reverend claimed he was our friend…”

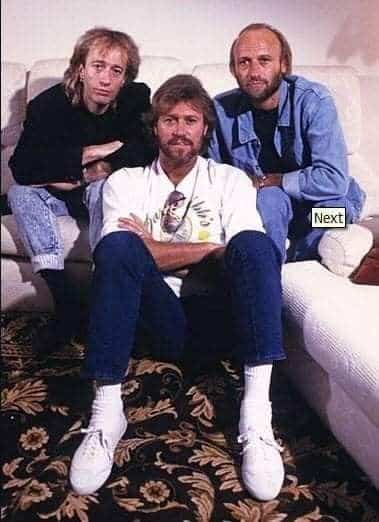

This is not a story of gentle heartbreak or sun-dappled bliss. This is the sound of a man facing the ultimate, inescapable deadline. Before the full-blown, shimmering falsetto of their disco era, before the stadium-filling Saturday Night Fever phenomenon, the Bee Gees—Barry, Robin, and Maurice Gibb—were mastering the art of the melodramatic, symphonic pop single. And among their early canon, I’ve Gotta Get A Message To You is arguably the darkest, most devastating piece of music they ever crafted.

It wasn’t initially featured on the UK release of their 1968 album, Idea, but it was a crucial inclusion on the US edition and was a standalone single that became their second UK number-one hit, reaching the top ten in the US as well. Its success cemented the Brothers Gibb as masters of the high-drama three-minute pop song. The track was a product of the period when their creative output was almost impossibly prolific, working with producer and manager Robert Stigwood, who helped package their baroque sensibilities for a global audience. Stigwood, along with the Bee Gees themselves, is credited with producing this compact opera, ensuring that every element—from the crisp drum attack to the soaring violins—served the central tragedy.

The sheer audacity of the lyrical premise, penned by all three brothers, remains startling. It’s a first-person plea from a man who has murdered his wife’s lover and is now minutes from execution in the electric chair. His one thought is not repentance, but a final, desperate message of love and assurance to his loyal wife. The song’s structure and instrumentation function not as mere backing, but as the relentless, ticking clock of his final moments.

Robin Gibb, whose distinctively quivering, slightly haunted vibrato was the signature of their early period, takes the lead vocal on the verses, embodying the condemned man’s raw panic. His delivery is a masterful study in controlled hysteria, conveying the desperation without ever tipping into full-blown screeching. It’s an intimate performance, almost too close for comfort, as if we are the chaplain sitting beside him. When Barry takes the second verse, the tone shifts slightly—a moment of solid, grounded finality that underscores the man’s grim situation. The contrast between Robin’s ethereal, pleading tone and Barry’s earthier resonance creates a duality that mirrors the contrast between the man’s soul and his mortal end.

The arrangement is a lesson in dynamic tension. The song begins with the somber thud of the drums and a minor-key progression, immediately setting the tone of impending doom. The bedrock of the rhythm section is tight and precise, anchored by Maurice Gibb’s solid bass guitar line. The instrumentation builds swiftly into the sweeping, glorious melodrama of the chorus. This is where the song truly earns its ‘baroque pop’ descriptor. We are talking about wall-to-wall sound: lush, soaring strings that lift the entire chorus to a pitch of near-transcendent anguish.

The string arrangement is not just ornamentation; it’s a character in the drama, providing the emotional catharsis the narrator cannot fully articulate. They swirl and crest, a counterpoint to the insistent, almost funereal rhythm established by Colin Petersen’s drums. Maurice’s understated piano work holds the harmonic center, supporting the vocal trade-offs. His Mellotron adds an organ-like texture in places, contributing to the vaguely religious, confessional atmosphere evoked by the presence of the Reverend.

There’s a beautiful, unsettling juxtaposition at work here. The theme is pure darkness—a capital crime and its ultimate consequence—but the sound is absolutely radiant pop. It’s meticulously crafted to lodge in your ear, to be hummed on the street. This contrast is the Bee Gees’ great genius of the late 60s: making the unbearable beautiful.

I remember once trying to explain this piece of music to a younger listener, someone accustomed only to the crystal-clear fidelity of contemporary digital tracks. I put on the original vinyl version, the one where the mono mix on the single reportedly ran slightly faster, adding to the urgency. We listened not on expensive studio headphones but through a home audio system, the warm saturation of the vintage recording filling the room. The subtle imperfections, the slightly compressed yet powerful sound, the immediacy of that lead vocal—it makes the story real.

The simplicity of the chord changes in the verse gives way to a complex, multi-layered texture in the chorus, demonstrating a remarkable economy of expression. They manage to evoke an entire life’s tragedy—love, crime, regret, and goodbye—in under three minutes.

“It is a high-tension wire stretched taut across a field of elegant, heartbreaking melody.”

This ability to fuse a morbid narrative with such infectious pop structure is a masterclass in songwriting. It’s why this single has such staying power, reaching beyond the typical nostalgia for the 1968 chart era. For someone just learning the craft, dissecting the transition from the subdued urgency of the verse to the explosive emotion of the chorus is more valuable than any formal sheet music lesson. It’s about emotional architecture.

The song’s power is a universal one. Who hasn’t felt that desperate, last-minute need to communicate something vital to the person they love, to reach out across an impossible chasm? The scaffold may be an electric chair, but the feeling is that of any terrible, irreversible separation—a sudden loss, a final door closing, a missed connection that defines a lifetime of regret. It’s a compressed tragedy that feels as immediate today as it did decades ago.

The Bee Gees in 1968 were already operating at an extremely high level, exploring sophisticated lyrical concepts with arrangements that married the rock band format with classical elements. I’ve Gotta Get A Message To You is a profound, compelling testament to their brilliance before they became the other Bee Gees—the disco superstars. It remains a pinnacle of cinematic pop that deserves to be revisited, to be properly heard again, not as a period piece, but as a chilling, timeless transmission from the edge of oblivion.

Listening Recommendations

- The Moody Blues – Nights in White Satin: For the perfect blend of classical orchestration and rock band performance, centered on a dramatic vocal.

- Procol Harum – A Whiter Shade of Pale: Shares a similar grand, melancholic, organ-driven, and slightly dark baroque pop atmosphere from the same era.

- Scott Walker – Jackie: A track with equally theatrical, almost morbidly dramatic lyrics presented within a lush, sophisticated pop arrangement.

- The Zombies – Time of the Season: Captures that same late-60s British pop sound where the rhythm section and keyboards create a subtly tense backdrop.

- Elvis Presley – In the Ghetto: Another powerful story-song from 1969 with a narrative of social tragedy that uses orchestration to amplify its emotional weight.

- The Bee Gees – New York Mining Disaster 1941: For a comparison of an earlier Gibb brothers narrative single that also builds intense atmosphere from a tragic scenario.

Video

Lyrics: I’ve Gotta Get A Message To You

The preacher talked with me and he smiled

Said, “Come and walk with me, come and walk one more mile

Now for once in your life you’re alone

But you ain’t got a dime, there’s no time for the phone.”I’ve just gotta get a message to you

Hold on, hold on

One more hour and my life will be through

Hold on, hold onI told him I’m in no hurry

But if I broke her heart, then won’t you tell her I’m sorry

And for once in my life, I’m alone

And I gotta let her know just in time before I goI’ve just gotta get a message to you

Hold on, hold on

One more hour and my life will be through

Hold on, hold onWell I laughed, but that didn’t hurt

And it’s only her love that keeps me wearing this dirt

Now I’m crying, but deep down inside

Well I did it to him, now it’s my turn to dieI’ve just gotta get a message to you

Hold on, hold on

One more hour and my life will be through

Hold on, hold onI’ve just gotta get a message to her

Hold on, hold on

One more hour and my life will be through

Hold on, hold on

I’ve just gotta get a message to her

Hold on, hold on