Table of Contents

ToggleWhen most people hear “Jailhouse Rock,” their minds jump straight to 1957 — striped prison uniforms, sharp choreography, and Elvis Presley at the peak of his early movie-star magnetism. That version is iconic, frozen in black-and-white cool, endlessly replayed as a symbol of rock and roll’s rebellious youth. But more than a decade later, Elvis returned to the same song and transformed it into something deeper, tougher, and far more personal.

The 1968 Comeback Special didn’t just revive Elvis Presley’s career — it redefined his relationship with his own legacy. And nowhere is that more electrifying than in his reimagined performance of “Jailhouse Rock.”

A King at a Crossroads

By the late 1960s, the music landscape had shifted dramatically. The British Invasion had come and reshaped pop culture. Psychedelic rock, protest songs, and new countercultural voices were dominating the charts. Meanwhile, Elvis — the man who helped ignite the rock and roll revolution in the first place — had spent much of the decade in Hollywood, making a long string of formulaic films and soundtrack albums that rarely captured the raw spark of his early years.

To many critics, Elvis had become a relic of a previous era — a symbol rather than a living force.

The ’68 Comeback Special changed that narrative in a single night.

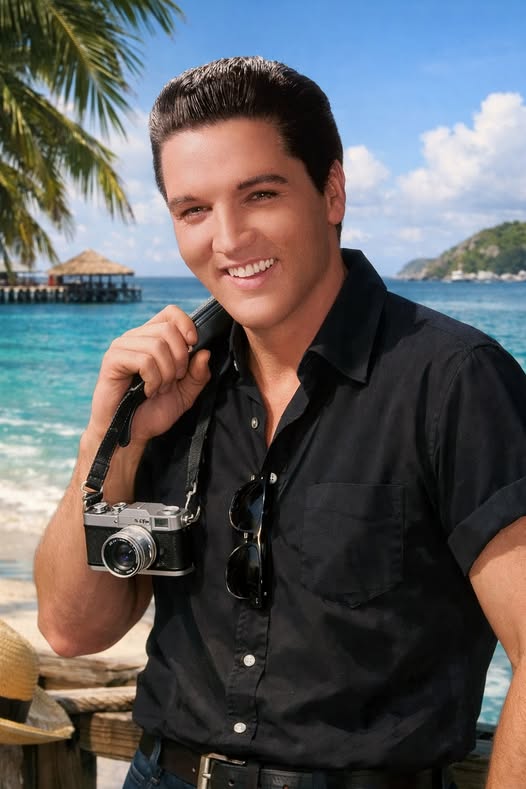

Broadcast on NBC, the special stripped away the glossy movie sets and placed Elvis back where he belonged: in front of a live band, with a guitar in his hands and fire in his voice. Dressed in black leather and framed by dramatic lighting, he looked less like a movie idol and more like a rock and roll outlaw reclaiming his throne.

And when the opening riff of “Jailhouse Rock” kicked in, it was clear this was not going to be a nostalgia act.

A Song Reclaimed, Not Repeated

The original “Jailhouse Rock” was playful, cheeky, and built for the big screen. The 1968 version is leaner and harder. The tempo feels tighter. The rhythm section punches with confidence instead of swing. The guitars bite. There’s a muscular urgency to the arrangement that mirrors the musical evolution happening around him.

Most importantly, Elvis sings it differently.

In 1957, his voice had a youthful swagger — smooth, teasing, and light on its feet. In 1968, there’s grit in the tone, a rasp that comes from experience, frustration, and hunger. Every line feels less like acting and more like testimony. He’s not playing the role of a rebellious inmate anymore; he sounds like a man fighting to prove he still belongs in the house he helped build.

That subtle shift changes everything.

The playful humor of the original gives way to something more intense. His phrasing is sharper. He leans into certain words, stretches others, and snaps back with rhythmic precision. It’s controlled, but it feels dangerous — the kind of performance where you sense anything could happen next.

The Power of the Setting

Part of what makes this version so unforgettable is the staging. Gone are the elaborate sets and backup dancers. Instead, the Comeback Special uses tight camera angles, stark lighting, and a stage setup that brings the audience almost uncomfortably close.

You can see the sweat. The half-smiles. The quick glances between Elvis and his band.

That intimacy turns “Jailhouse Rock” from a theatrical number into a live-wire moment. Elvis moves with confidence but not choreography. His body language is loose, instinctive — a reminder that before he was a movie star, he was a live performer who thrived on the energy of the room.

And the room responds.

The crowd’s excitement is audible, feeding back into the performance. It becomes a loop of energy: band to Elvis, Elvis to audience, audience back to stage. The result feels less like a television segment and more like a club show that somehow made it onto national broadcast.

Symbolism Beyond the Music

Choosing “Jailhouse Rock” for this special wasn’t accidental. The song had been one of the pillars of Elvis’s early superstardom. Revisiting it in 1968 could have felt like a safe, nostalgic nod to the past. Instead, it became an act of artistic reclamation.

He wasn’t just revisiting an old hit — he was proving that it still belonged to him.

At a time when many believed rock had passed him by, Elvis stepped onto that stage and delivered a performance that said otherwise. He didn’t try to imitate the new trends. He didn’t soften his style. He doubled down on what made him powerful in the first place: rhythm, attitude, and undeniable charisma.

That confidence ripples through “Jailhouse Rock.” You can feel that he knows exactly what this moment means. There’s joy in it, but also relief — like an artist finally allowed to breathe after years of creative confinement.

Why It Still Matters

Decades later, the ’68 Comeback Special is often cited as one of the greatest career revivals in music history. And performances like “Jailhouse Rock” are the reason why.

It reminds us that great artists aren’t defined by trends — they define themselves by their ability to reconnect with their core. Elvis didn’t chase the sound of 1968. He rediscovered the spirit that made 1956 explode and brought it forward with maturity and muscle.

For modern viewers, the performance still crackles with life. It doesn’t feel like a museum piece. It feels immediate, human, and thrillingly imperfect. You see the effort. You hear the breath between lines. You feel the risk.

That’s rock and roll at its most honest.

Turning the Lights Back On

In the end, the 1968 version of “Jailhouse Rock” stands as more than a reinterpretation of a classic song. It’s a declaration of identity. A reminder that Elvis Presley wasn’t just the King because of early fame — he earned the crown again when it mattered most.

Under those hot stage lights, dressed in black leather, guitar slung over his shoulder, Elvis didn’t look like a man revisiting old glory. He looked like a man turning the lights back on in a house that had been waiting for him.

And when he sang “Everybody in the whole cell block…” it wasn’t just a lyric from a hit record.

It was the sound of rock and roll roaring back to life.