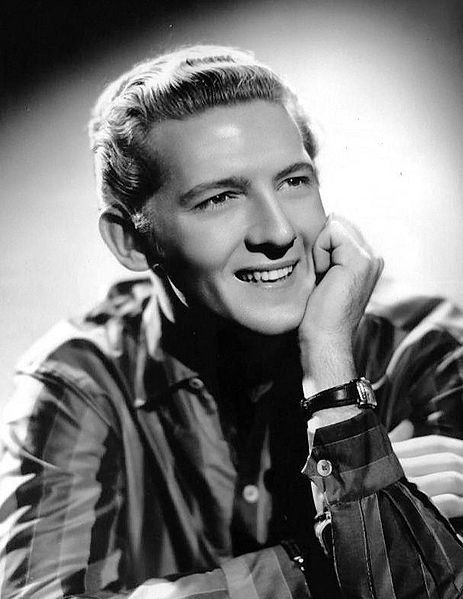

Jerry Lee Lewis’s “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” is one of those rare recordings that still sounds combustible the moment the needle drops. Cut at Sun Studio in early 1957 and issued as Lewis’s second single that spring, it fused boogie-woogie drive, honky-tonk attitude, and R&B bite into a new, unruly shape—and in the process gave rock ’n’ roll one of its defining performances. The record’s ascent—Top 3 on Billboard’s pop chart and No. 1 on both the R&B and country lists—made “The Killer” a household name and left an imprint that every subsequent piano-pounding rocker has felt.A single first, then an album staple—how this track fits into Lewis’s catalog

Unlike many hits that debut on LP, “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” arrived as a stand-alone 45 on Sun Records. In fact, when Sun issued Lewis’s self-titled debut album in 1958, the label surprisingly did not include either “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” or “Great Balls of Fire,” preferring a different selection of material. Only later did “Shakin’” become the anchor of numerous collections, among them the widely circulated The Golden Rock Hits of Jerry Lee Lewis (1964), ensuring that new listeners encountered the song in album form even if it had started life as a single. This release pattern—single first, compilation later—matters because it explains why the track feels like a calling card as much as a cut: it’s the performance Sun used to announce Lewis to the world, then it became the emblem around which albums were curated.

The band, the room, the sound

Part of the record’s power is its sparseness. The core lineup is a trio: Lewis on lead vocal and piano; J.M. Van Eaton on drums; Roland Janes on electric guitar. That’s it—no section of horns, no layers of overdubs, and often no discernible bass part because Lewis’s left hand does the heavy lifting. The arrangement pushes all attention toward the keyboard’s relentless churn and the vocal’s playful command. Producer/engineer Jack “Cowboy” Clement supervised the session at Sun, and the famous Memphis slapback echo creates a vivid, roomy halo that makes the piano feel like it’s leaping off the tape. Listen for Van Eaton’s crisp snare accents and Janes’s muted, percussive figures—they act like guardrails for Lewis’s right-hand glissandos and treble stabs, tightening the groove without ever taming it.

That slapback is crucial to the so-called “Sun Sound.” Sam Phillips—Sun’s founder and the architect of so many epochal ‘50s sessions—prized both the intimacy of small ensembles and the psychological bigness that echo could impart. Technically, it was achieved with a short, single-repeat delay that thickens transients (piano hammers; snare hits) without muddying them, giving records a distinct, live-in-the-room presence. “Shakin’” uses the effect to heighten the sensation of movement; the echo almost behaves like another dancer in the room, a second body shadowing the beat.

What you actually hear: arrangement and performance details

“Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” is built on a sturdy 12-bar chassis, but it doesn’t behave like a textbook blues. The first half establishes a locomotive groove: left-hand octaves (or tenth-based patterns) pump quarter- and eighth-note energy, while the right hand drops ornamental trills, blue-note crushes, and those signature palm-smeared slides across the upper keys. Lewis’s vocal is a master class in rhythmic phrasing—behind the beat when he wants to imply swagger, on top of it when he wants to incite the room—and his call-and-response with the piano turns the instrument into a co-conspirator. When the famous breakdown arrives, the band pulls back to a whisper; Lewis narrates, coaxes, and teases the crowd with command-and-wink lines before slamming the door with a final chorus at full tilt. The arrangement is a tutorial in tension and release, replacing sheer loudness with dynamic storytelling.

Technically inclined listeners will notice a few specific piano moves. In the breakdown, Lewis often reduces his left-hand pattern to a sparse, heartbeat pulse—just enough to keep time—freeing his right hand to chatter in short, syncopated figures that complement the vocal. During the choruses, he sometimes shifts to rolling triplets in his right hand, which is part of why the groove feels like it’s accelerating even when the tempo doesn’t change. And that hard-pedaled sustain before the last exclamation point? It lets the final chord bloom into the room, a satisfying, ringing pay-off that makes the whole take feel inevitable.

Country roots, gospel fire, rock ’n’ roll attitude

Historically, the record sits at the crossroads of styles. Its bones come from the hillbilly-boogie tradition—think Moon Mullican and Merrill Moore—but the execution is raucous rock ’n’ roll. The lyric’s flirtatious naughtiness channels jump blues theater; the piano’s voicings owe as much to tent-revival gospel as they do to barroom honky-tonk. That hybrid DNA is why the single could dominate three different charts at once: country, R&B, and pop. If you grew up on Nashville steel guitar and shuffles, you recognize the back-porch party; if you were raised on Ray Charles and Big Joe Turner, you recognize the nightclub electricity; and if you were a teenager in 1957, you simply recognized freedom—something to shout along with and dance to until the floorboards begged for mercy.

Who wrote it—and why Lewis’s version became the version

The authorship story is tangled (as many mid-century songs are). The tune is usually co-credited to Dave “Curlee” Williams and Roy Hall, and there were pre-Lewis recordings—Big Maybelle’s R&B treatment chief among them—but Jerry Lee reshaped the number so dramatically that it’s not just a cover; it’s a reinvention. He changed the feel, inserted that theatrical breakdown, and sharpened the innuendo without crossing into parody. It’s a textbook case of how interpretation can become authorship in the ears of the public: once you’ve heard Lewis’s cut, it’s hard to imagine the song any other way.

Why the sound still shocks—production and engineering notes

Sun’s slapback adds presence, but it’s the placement of instruments in the image that makes “Shakin’” feel so alive. The piano dominates the midrange, where rock guitars would later live, which explains part of the record’s novelty to modern ears: it’s a rock hit driven by keys, not six-string distortion. Janes’s guitar is mixed almost like additional percussion—percussive chanks, clipped fills, and a slightly damped tone that keeps the spectrum clear for the vocal and piano harmonics. Van Eaton keeps time with a lightly swung backbeat and neatly placed ride-cymbal pings; he plays with the piano rather than on top of it, giving the take elasticity instead of rigid gridlock. Professionals talk about “air” in classic records; here, “air” is the literal space around a trio performing in a room, captured on magnetic tape with minimal circuitry between performance and playback. It’s one reason “Shakin’” remains a production reference—an analogue of kinetic energy.

A note on the album context—why compilations matter here

Because “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” was released as a single in 1957, the first LP that introduced many listeners to the track arrived later via compilations. The 1958 Jerry Lee Lewis debut LP notably omitted the hit; in the early-‘60s Sun era and beyond, collections began to canonize it. Among those, The Golden Rock Hits of Jerry Lee Lewis (1964) served as an entry point for a new generation, assembling the big bangers in one package and cementing “Shakin’” as Lewis’s signature. For modern listeners used to discovering music via playlists and anthologies on music streaming services, that history matters; this is a song built to lead a compilation, to kick the door down first and ask questions later.

What musicians hear in the track

Keyboard players hear a masterclass in left-hand economy and right-hand flair. The left hand doesn’t overcomplicate; it provides relentless propulsion, sometimes walking, sometimes pumping octaves, always supportive. The right hand is where the personality lives—raking glissandi, rapid grace-note clusters, sly chromatic scoops that push the vocal forward. Guitarists, meanwhile, hear a study in taste. Roland Janes’s tone is slightly muffled, tucked behind the vocal, which lets his rhythm lock with the snare. When he does step out for a lick, the part is concise, functional, and perfectly placed. Drummers hear a deep pocket with a splash of swing—no double-kick fireworks, just dance-floor truth. Aspiring players who feel the itch after listening will find no shortage of piano lessons online walking through boogie-woogie patterns, stop-time breakdowns, and Sun-style turnarounds—though the Lewis factor, the conjurer’s grin and showman’s nerve, can’t be taught so much as absorbed.

Lyrical stance: playful, not explicit

One secret to the record’s durability is its balance of invitation and restraint. The lyric promises a party—“come on over, baby”—but it never tips into explicit detail. Instead, Lewis’s ad-libs do the heavy lifting: the hush in the breakdown, the mock-instructional tone (“stand in one spot and wiggle around just a little bit”), the laughter that bubbles up as the band re-enters. It’s all theater, and it’s all in the performance. The words set a scene; the voice sells the experience.

Country & classical ears welcome

If you come from a country background, you’ll recognize the bar-band conviviality and honky-tonk storytelling in Lewis’s delivery. If your tastes tilt classical, listen for dynamics and articulation—the rapid alternation between staccato punches and legato smears; the disciplined pedal work that keeps lines distinct despite the speed; the micro-ritardando into turnarounds that adds breath before the next chorus. The piece is simple in harmonic terms but intricate in execution, and that paradox—a basic frame animated by fearless touch—is why pianists keep returning to it.

The numbers that made history

The commercial story is as bold as the performance. After its April 1957 release, “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” fought through the season dominated by Elvis’s “All Shook Up,” then powered into late summer and fall, peaking at No. 3 pop while topping both R&B and country charts. That triple-crossover is rare; it testifies to how cleanly the record erased format lines. Decades later, the Library of Congress added the single to the National Recording Registry, recognizing not only its historic impact but also its continuing resonance as a document of American musical invention.

Instruments and sounds—what to listen for on repeat

-

Piano: The dominant voice. Hear the crisp attack captured by Sun’s miking, the tactile grit of hard-struck hammers, and the bright upper-register runs.

-

Guitar: A supportive, slightly damped timbre, often reinforcing back-beat accents. When Janes nudges into a phrase, it’s like an elbow in the ribs—playful, pointed, short.

-

Drums: Snare-heavy backbeat with judicious use of ride cymbal; the kit is tuned tight, creating headroom so the piano can surge without distortion.

-

Room & Echo: A fast, single-repeat slapback that adds space without blur—Sun’s sonic signature of the era.

As a “piece of music, album, guitar, piano” touchstone, the record feels both distilled and inexhaustible: you get a complete performance in under three minutes, yet there’s always another detail to catch—a grace note here, a wink in the phrasing there, a drum ghost-note that you somehow missed the first hundred times.

Why it still works in 2025

Contemporary productions are bigger, wider, and louder, but few feel more alive than this tape from a small Memphis room. The difference is performance energy riding a simple arrangement. Strip away the studio trickery and what remains must stand on touch, time, and personality. That’s what Lewis, Van Eaton, and Janes captured: three musicians playing to the edge of control and never falling off. For listeners discovering the track today—perhaps via music streaming services that place it in a “Rockabilly Essentials” playlist—the shock is the same as in 1957: the feeling that someone just kicked a door in and yelled, let’s go.

Recommended listening—songs that live in the same world

If “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” lights you up, chase that fire through these cuts:

-

Jerry Lee Lewis – “Great Balls of Fire” (another Sun-era piano blitz that pairs mischief with melody)

-

Jerry Lee Lewis – “Breathless” (tighter, poppier, but charged with the same boogie energy)

-

Jerry Lee Lewis – “High School Confidential” (rockabilly swagger from the 1958 LP)

-

Little Richard – “Good Golly, Miss Molly” (if piano is your chosen weapon, this is the other canonical blast)

-

Carl Perkins – “Blue Suede Shoes” (Sun-baked rockabilly with a guitar-lead focus)

-

Bill Haley and His Comets – “Shake, Rattle and Roll” (jump-blues spirit meeting clean-cut drive)

-

Big Maybelle – “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” (a pre-Lewis version that shows how arrangement transforms material)

-

Moon Mullican – “Pipeliner Blues” or “I’ll Sail My Ship Alone” (for the country-boogie lineage behind Lewis’s keyboard style)

Final thoughts

“Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” endures because it captures a moment where style, personality, and studio technique clicked perfectly. The piano doesn’t just accompany; it leads. The guitar doesn’t compete; it complements. The drums don’t push; they pivot, letting Lewis accelerate by feel. And the room—Sun’s fabled echo chamber in miniature—turns three players into a riot. However you approach it—as a history lesson, a performance textbook, or just three minutes to make the world feel louder and freer—it remains a masterwork of economy and impact. It’s the kind of record that reminds you why the simplest tools, wielded with conviction, can still sound like the future.