There are songs that age quietly, slipping into the background of nostalgia. And then there are songs that refuse to behave, that keep barging into the present tense no matter how many decades pass. John Fogerty’s “Fortunate Son” belongs firmly to the second category. In its live form, the song doesn’t just revisit the past—it confronts the now, flaring up like a signal fire that dares the crowd to answer back.

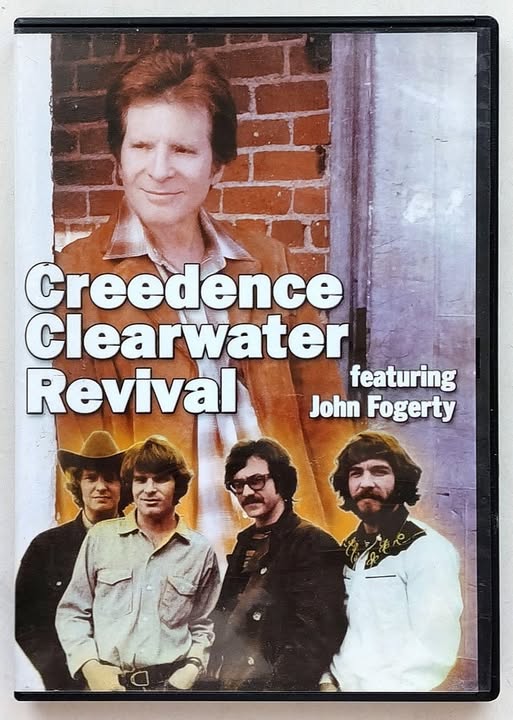

Originally written and recorded with Creedence Clearwater Revival in 1969, “Fortunate Son” arrived at a time when American optimism was cracking under the weight of the Vietnam War and the ugly realities of class privilege. The studio version was lean, sharp, and furious—a three-minute shot of righteous anger that cut straight through the radio static. But when Fogerty performs the song live, it transforms into something larger than a protest anthem. It becomes a communal ritual. The crowd doesn’t just listen; they testify.

A Song Born in Fire, Forged in Front of a Crowd

Fogerty has often spoken about how quickly “Fortunate Son” poured out of him—written in a sudden rush after watching how wealth and political connections shielded some families from the draft while others bore the cost. That speed shows in the song’s DNA. There’s no hedging, no poetry to soften the blow. It’s direct, percussive, and unapologetically angry. The opening riff hits like a raised fist, and by the time the first line lands, the argument is already underway.

Onstage, that argument becomes shared property. A live performance turns the song into a call-and-response between the artist and the audience. You can hear it in the way crowds instinctively lock into the chorus—thousands of voices aligning on a single, defiant refusal. In that moment, the song stops being a relic of the Vietnam era and starts sounding like a living commentary on any system that protects the powerful while demanding sacrifice from everyone else.

From Studio Document to Living Evidence

Studio recordings are important. They’re documents—snapshots of a moment in time. But live recordings are evidence. They show how a song behaves when it’s let loose in the wild. One of the most revealing chapters in the live life of “Fortunate Son” came decades later with Fogerty’s solo concert album Premonition, recorded in 1997. By then, Fogerty was publicly reclaiming the songs he wrote for Creedence after years of legal and contractual battles had kept him from performing them freely.

Hearing “Fortunate Son” in that context feels different. It’s not just a hit from the past being dusted off for applause; it’s an artist reuniting with his own voice. The performance carries the weight of history—personal and cultural—yet it also feels startlingly current. The anger hasn’t cooled into nostalgia. If anything, it’s sharpened by experience. The song sounds like a tool Fogerty can still reach for whenever the world starts congratulating itself a little too loudly.

Why the Live Version Hits Harder

There’s a particular electricity that only happens in a room full of people singing the same truth at the same time. Live, “Fortunate Son” sheds any hint of being a period piece. The Vietnam War imagery that films and TV have leaned on for decades burns away, and what’s left is the song’s core: a blunt critique of privilege and performative patriotism. The flags and slogans that try to wrap injustice in respectability don’t stand a chance when a crowd is chanting the chorus back at the stage.

The tempo feels tighter live. The guitars bite harder. Fogerty’s voice, roughened by years on the road, carries more grain and gravity. That texture matters. It turns the song from youthful outrage into seasoned conviction. You can hear the difference between anger that’s discovered a problem and anger that’s lived with it, watched it mutate, and still refuses to accept it.

The Comfort of Clarity

There’s a strange comfort in the bluntness of “Fortunate Son,” especially when it’s performed live. The song doesn’t ask you to decode metaphors or wrestle with ambiguity. It tells you exactly what it’s mad about. In a world that often feels fogged up with spin, that kind of clarity can be bracing. Live performance gives listeners a way to participate in that clarity. Singing along becomes a small, human act of resistance—not against a specific war alone, but against the broader idea that inequality is just the way things have to be.

And that’s the secret power of the live version: it converts solitary frustration into shared release. For a few minutes, strangers become a choir of dissent. You stamp your foot in time with people you’ve never met. You shout the same lines into the same air. The anger doesn’t disappear, but it changes shape. It becomes solidarity.

Not Nostalgia—Conscience

“Fortunate Son” has been used so often in popular culture that it risks becoming shorthand—an easy cue for “this is Vietnam-era America.” But when Fogerty brings it to life onstage, the shorthand collapses. The song stops pointing backward and starts pointing outward. It asks uncomfortable questions about who gets protected by systems of power and who gets exposed to their consequences. Those questions haven’t expired. They’ve just changed uniforms.

That’s why the live performance endures. It isn’t about reliving the 1960s. It’s about refusing to let the present off the hook. Under stage lights, with the crowd roaring the chorus back, “Fortunate Son” feels less like a memory and more like a moral checkpoint—a reminder that patriotism without accountability is just noise.

In the end, the magic of “Fortunate Son (Live)” is how it turns anger into communion. It doesn’t offer easy answers, and it doesn’t pretend the world is fair. What it offers is a moment of shared honesty—a chance to stand in a room full of people and admit, out loud, that something still isn’t right. For a few minutes, that admission becomes music. And music, when it’s this alive, can still feel like a flare in the night—bright enough to gather people around it, even decades after it was first lit.