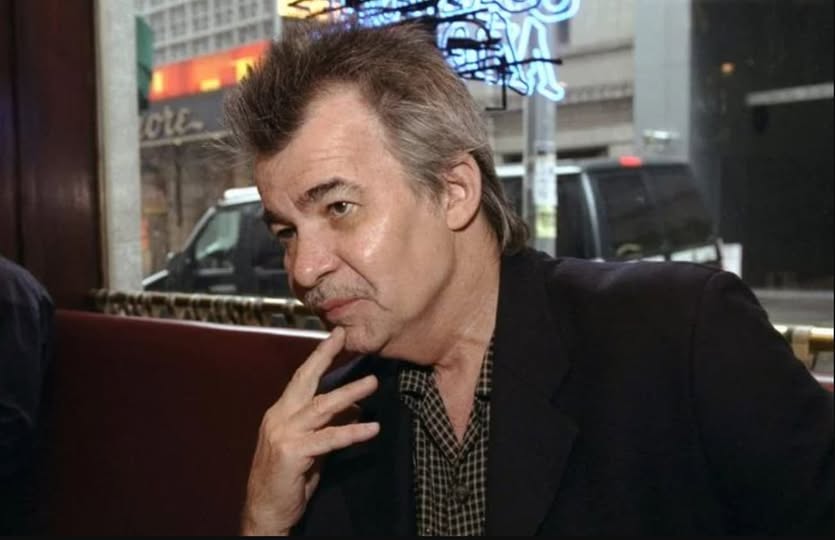

There’s something profoundly disarming about stepping into the Nashville home of John Prine. The setting is simple—comfortable couches, guitars within arm’s reach, sunlight pooling across hardwood floors—but the stories told there stretch across decades of American songwriting. What unfolds in this intimate video portrait is less an interview and more a living-room meditation on craft, resilience, and the quiet, stubborn devotion required to keep writing songs long after the applause fades.

At the center of the conversation is The Tree of Forgiveness, a late-career masterpiece that Prine never originally intended to make. Released in 2018, the album marked his first collection of new material in over a decade. It would go on to earn Grammy recognition and remind the world that the poet laureate of the everyday still had something vital to say.

But as Prine explains, the album’s existence began not with ambition, but with gentle insistence—from family.

A Hotel Room, Three Guitars, and a Push from Love

The genesis of The Tree of Forgiveness reads like one of Prine’s own lyrics: modest, slightly absurd, and quietly profound. Encouraged by his wife, Fiona Whelan Prine, and their son Jody, Prine was essentially exiled to a Nashville hotel room. No distractions. No excuses. Just three guitars and boxes of unfinished lyric sheets—some scribbled on cardboard scraps, others on napkins or old envelopes.

It was an act of loving intervention.

For years, Prine had accumulated fragments—verses half-sung into tape recorders, lines jotted down in moments of inspiration, images without homes. Like many writers, he was adept at beginning songs. Finishing them, however, required a different kind of discipline. The hotel room became both sanctuary and pressure cooker: a space where the only task was to sit, sift, and shape.

In that temporary solitude, something remarkable happened. The songs that emerged—like “Summer’s End” and “When I Get to Heaven”—felt effortless, as if they had always existed and simply needed permission to surface. The isolation didn’t silence him; it clarified him.

The Philosophy of a Working Songwriter

Throughout the video, Prine returns again and again to the idea that songwriting is work. Not mystical revelation. Not tortured genius. Work.

He speaks about syllables fitting melodies before meaning even enters the equation. About the rhythm of words and how sometimes a line stays because it sounds right, even if its significance reveals itself later. It’s a refreshingly unromantic view of art—one rooted in craftsmanship rather than spectacle.

Prine trusted listeners to do their own emotional heavy lifting. He believed in images: a broken radio, a pawn shop window, a gravestone with a simple inscription. These were not abstract metaphors; they were pulled from his own life. His father’s old Zenith radio. The mail routes he worked in suburban Chicago before fame found him. The clutter of everyday American existence.

That grounding in lived experience explains how a young Prine, barely in his twenties, could write songs like “Hello in There” and “Angel from Montgomery” with such startling empathy for aging, loneliness, and regret. He didn’t overthink what he “should” or “shouldn’t” write about. He simply wrote what moved him.

In the video, that humility is still present. Even after Grammy wins and Hall of Fame inductions, he speaks like a man still trying to get the second verse right.

Family: The First Audience

If The Tree of Forgiveness has a hidden theme, it is gratitude—especially toward family. Prine describes how his grandparents shaped his ear for storytelling. His mother filled rooms with colorful characters and affectionate nicknames. His father introduced him to music, politics, and the ritual of sharing a beer.

Those early influences echo through every line he ever wrote.

In the Nashville living room, photos sit nearby—reminders of the people who pushed him, supported him, and sometimes gently cornered him into finishing what he started. Fiona, in particular, emerges as both partner and quiet producer, believing in the songs long before they were complete.

Prine makes it clear: this album was not just his triumph. It was a family project. From the creative nudge to the record label’s support to the artwork and photographs he carried on tour, The Tree of Forgiveness became a shared achievement.

In an industry often obsessed with individual genius, that collective spirit feels radical.

Illness, Survival, and a Sharpened Perspective

No conversation with John Prine in his later years could avoid the subject of illness. Having survived cancer twice, he speaks not with bitterness, but with clarity. Survival stripped away certain illusions. It made everyday pleasures sharper—morning coffee, laughter at the dinner table, the feel of a guitar neck in hand.

The brush with mortality deepened his songwriting without darkening it. If anything, the humor became more mischievous, the tenderness more distilled. “When I Get to Heaven,” with its playful promises of vodka-and-ginger-ale toasts and cosmic jukeboxes, feels both irreverent and sincere—a wink at death rather than a surrender to it.

Gratitude replaced urgency. Recognition felt sweeter, but less necessary. The Grammy nominations that came decades after his first were appreciated, yet they were not the point. The point was the song. Always the song.

A Legend Who Refused to Act Like One

What makes this living-room conversation so powerful is its lack of pretense. There are no grand pronouncements about legacy. No dramatic pauses to underline importance. Instead, Prine talks the way he writes: conversationally, wryly, occasionally drifting into a story that starts in one decade and lands in another.

He describes songwriting as digging through junk to find a gem. Most of what you sift through won’t shine. But every now and then, something catches the light.

That metaphor captures his entire career. From his early days in Chicago folk clubs to global tours and critical acclaim, Prine never abandoned the image of himself as a worker in a workshop—sorting, polishing, discarding, keeping.

By the end of the video, the viewer feels less like an audience member and more like a guest who lingered after dinner. The guitars remain within reach. The conversation slows. The sense of time stretches comfortably.

John Prine does not emerge as a distant icon carved in marble. He appears instead as what he always claimed to be: a working songwriter who believed music travels best hand to hand, heart to heart, generation to generation.

And in that Nashville living room—surrounded by family, memory, and the gentle echo of unfinished lines—you understand that The Tree of Forgiveness was never just an album. It was proof that even after decades on the road, even after illness and accolades, the well of honest storytelling had not run dry.

It simply needed a quiet room, three guitars, and someone who loved him enough to say, “Finish the songs.”