The year is 1968, and the radio airwaves are a battlefield of sound—psychedelic rock is pushing boundaries, soul music is electrifying the charts, and the sheer power of the pop crooner still commands attention. Into this dynamic, often chaotic, landscape stepped a 21-year-old New Zealander named John Rowles, armed with a voice of remarkable depth and control. His weapon, a plaintive, deeply resonant single, was the English translation of a French hit: “If I Only Had Time.”

I remember hearing this piece of music late one night, a half-century removed from its release, its grand, cinematic sound cutting through the digital hiss of a quality premium audio system. It carried a gravity that felt out of sync with the relentless optimism of so much late-60s pop. This wasn’t a sun-drenched beach anthem; it was the confession of a soul realizing the tragic arithmetic of life: so much to do, so little time left to do it.

The Transatlantic Gambit and the Leander Touch

“If I Only Had Time” was Rowles’ first UK single and served as the cornerstone for his self-titled 1968 album on the MCA label. Its release was the culmination of a deliberate strategy by his Australian-born manager, Peter Gormley, to position Rowles in the mold of successful continental European and British balladeers like Engelbert Humperdinck. Rowles possessed the vocal charisma to stand alongside them, but he needed a signature song. Gormley, whose portfolio included Cliff Richard and Olivia Newton-John, signed Rowles and paired him with the versatile and highly respected producer and arranger, Mike Leander.

Leander, a man whose credits spanned from The Beatles to Marianne Faithfull, understood how to fuse classical ambition with pop immediacy. He took “Je n’aurai pas le temps,” a 1967 hit for French singer Michel Fugain, and, with new English lyrics by Jack Fishman, transformed it into a vehicle for Rowles’ rich baritone. The song would prove to be a tremendous launchpad, soaring to number three on the UK charts and achieving similar success across Europe and the Antipodes, instantly cementing Rowles as an international star.

Sound and Instrumentation: The Architecture of Yearning

The arrangement Leander crafted is the true genius stroke here, a meticulous exercise in musical architecture that elevates the core melody. The track opens simply enough—a melancholic, almost hesitant passage on the piano introduces the central harmonic progression, quickly followed by a gentle, brushed-snare rhythm section. The sound is dry, immediate, focusing all attention on Rowles’ initial vocal entry. His voice, at this point, is held in deliberate restraint, a whisper of longing.

But this simplicity is a deliberate contrast, a set-up for the orchestral sweep that defines the chorus. As Rowles launches into the title phrase, a curtain of lush strings rises behind him. Leander utilizes the strings not merely for ornamentation, but as a dynamic engine, their full, warm timbre swelling in a perfectly executed crescendo that mirrors the emotional outburst of the lyric. It’s a classic, mid-century pop device, but executed here with a rare precision and warmth. The brass section enters sparingly, delivering poignant, high-register counter-melodies in the latter verses, adding a metallic tang of desperation to the soft, velvet crush of the strings.

The rhythm section, while anchoring the pace, remains subtle. The guitar work is minimal—a faint, clean arpeggio occasionally emerges from the background, adding textural complexity without ever distracting from the voice or the orchestral drama. The drumming provides a steady pulse, employing soft mallets or brushes that keep the dynamic gentle yet urgent. The mic work on Rowles’ voice is close and intimate, capturing every subtle vibrato and breath, making the listener feel like a confidant to his private lament. The dynamic range, from the restrained verses to the full-throated chorus, demands attention, making it a favorite for audiophiles testing their studio headphones.

The Universal Truth of the Lyric

The lyrical theme, translated from the French original, taps into a universal truth that transcends the 1968 production style. It’s not just a love song; it’s an existential plea for extension. The singer isn’t asking for money or fame; he is begging for “a whole century” simply to spend with his beloved, because even a single lifetime is not enough.

“If I only had time, only time, so much to do / If I only had time, they’d be mine,” Rowles sings, his voice rich and full, yet laced with a poignant fragility that belies his youth. The song’s power comes from the contrast between the majestic, eternal sound of the orchestra and the simple, finite tragedy of the human clock. The arrangement is vast, but the emotional core is deeply personal.

“The grand, sweeping sound of this piece of music is merely the frame for a voice facing down the most elemental of human anxieties: running out of time.”

Rowles’ performance is a masterclass in controlled catharsis. He never over-sings, choosing instead to let the strength of his natural tone and phrasing carry the weight. He allows the melancholy to deepen, particularly in the quieter bridge sections, before leaning into the big, soaring moments where the melody lifts and the arrangement swells. It is the sound of restraint yielding to raw, but always elegant, emotion. This is why the song endures; it captures a moment of glamour, a big-budget ballad style, but anchors it with a gritty, relatable fear of ephemerality. The final, sustained note, fading out with the reverb tail of the strings, leaves a silence that echoes the space where all those unspent years were supposed to be.

Listening Recommendations: Ballads of Orchestral Longing

For those who appreciate the sweep, sincerity, and cinematic sound of “If I Only Had Time,” here are a few adjacent tracks to explore:

- “The Impossible Dream (The Quest)” – Richard Kiley (1965): Shares the same dramatic, aspirational, and highly-arranged mid-60s Broadway-to-Pop emotional scale.

- “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You” – Frankie Valli (1967): Features a similar structure, moving from a simple, intimate piano-led opening to a full, booming orchestral finale.

- “Love Story (Where Do I Begin)” – Andy Williams (1971): A comparable lush, Mike Leander-esque arrangement and vocal sincerity applied to a hugely successful cinematic theme.

- “Release Me” – Engelbert Humperdinck (1967): A contemporary single that showcases the same powerful male crooner style and big-band/orchestral pop production that Rowles was challenging.

- “It Must Be Him” – Vikki Carr (1967): Another example of a successful English-language cover of a French torch song, featuring soaring vocals over a dramatic string arrangement.

- “MacArthur Park” – Richard Harris (1968): An incredibly ambitious, long-form orchestral pop piece from the same year, demonstrating the era’s appetite for grandeur.

The passing of time is an inevitable, cruel process. But for the three minutes and twenty seconds of this song, John Rowles and Mike Leander built a golden refuge against it—a majestic, soaring bubble of sound where the dreams you’ll never get to pursue still feel close enough to touch. Turn it up again, and let the strings tell the story.

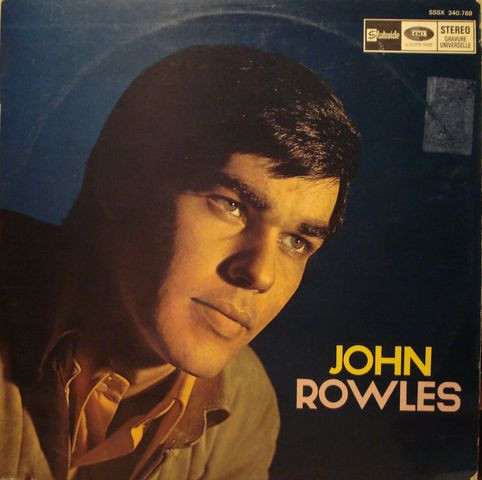

The YouTube video is a fan-uploaded version of the song, providing an immediate way to re-listen to this classic 1968 pop hit.

John Rowles – If I Only Had Time (Colour 1968)