It’s an hour I know well. The light hits the dust motes just right, illuminating everything you tried to forget the night before. The coffee tastes like ash. The street outside is quiet, not with peace, but with the profound, echoing silence of a town that has moved on to a different rhythm—the rhythm of church bells, of families gathering, of doing better. It’s the deep, inescapable solitude of a Sunday morning. This is the stage set by Kris Kristofferson, but it is Johnny Cash who walks onto it and makes it a timeless, visceral drama.

Cash’s 1970 single, “Sunday Morning Coming Down,” is not a protest song, nor is it a tragic murder ballad or a sentimental tear-jerker. It is, perhaps, something far more challenging: a piece of hyper-realistic autobiography, a snapshot of a man at his absolute lowest ebb. The original composition, written by Kristofferson reportedly while he was a struggling janitor in Nashville, was a radical departure for country radio. It spoke candidly of hangovers, cheap beer for breakfast, and wishing, Lord, that he was “stoned.”

The Man in Black’s Defining Moment

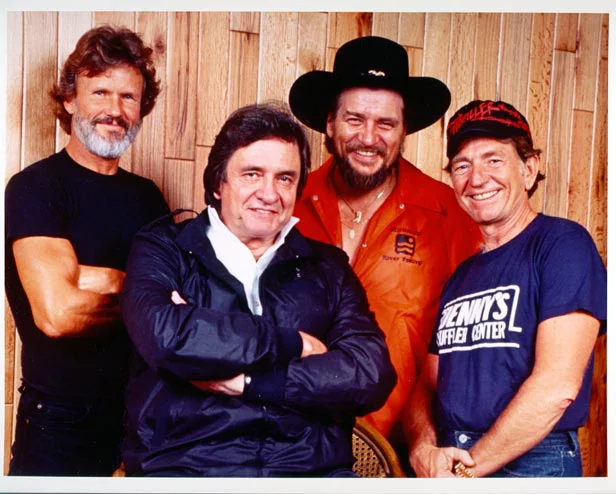

When Cash released his version, which quickly became a number one hit on the country charts and won the CMA Song of the Year, it wasn’t simply a cover; it was an act of reclamation, an endorsement that instantly legitimized the burgeoning Outlaw Country movement. Cash himself was a man who understood struggle, having battled his own demons with remarkable public transparency. He didn’t just sing Kristofferson’s words; he lived them into being.

The track was released on the The Johnny Cash Show album, a soundtrack companion to his enormously popular network television variety program. This context is crucial. Here was a man in 1970, with a major primetime show on ABC, daring to sing about drug use and despair to millions of American families. When network executives reportedly demanded he change the line “I’m wishing Lord that I was stoned,” Cash, ever the rebel, refused and sang the lyric exactly as written on national television. This defiance, captured in the song’s legacy, is as important as the recording itself. The producer on this era of Cash’s work was Bob Johnston, a veteran who had navigated the sessions of Bob Dylan and Simon & Garfunkel. Johnston’s touch here is one of masterful restraint, choosing atmosphere over polish.

Sound and Solitude

The arrangement is stripped back, but never thin. It begins with the unmistakable, resonant thrum of Cash’s voice, which acts as the lead instrument. The sonic palette is warm, almost sepia-toned, lending it the feel of an old photograph. The core rhythm section, the bedrock that had defined Cash’s sound for over a decade, is present but subdued. Marshall Grant’s bass lines are simple, thick pulses, anchoring the sorrow, while the drumming is minimal, often just a soft brush on the snare or a muted tap on the cymbal.

The defining instrumental texture, beyond Cash’s vocal delivery, is the interplay of two contrasting elements: the acoustic guitar work and the subtle piano filigree. The guitar, likely strummed by Cash himself or Luther Perkins’ successor, Carl Perkins, is a dry, woody sound, giving the song its rootsy, folk-country authenticity. It follows the vocal phrasing closely, a steady heartbeat beneath the lament. Meanwhile, a beautifully understated piano—playing quiet, almost ghostly chords—adds an unexpected layer of depth. It’s not a saloon piano, but a classical instrument providing harmonic counterpoint, a melancholy resonance that heightens the narrator’s emotional emptiness. It’s a masterful choice in orchestration, placing sophistication right alongside the raw grit.

The track’s dynamic range is incredibly narrow, holding a steady, almost conversational volume. This forces the listener to lean in, to pay attention, pulling us deep into the narrator’s headspace. The reverb is minimal, a dry, close-mic’d intimacy that makes you feel as though Cash is speaking directly into your studio headphones. It’s a stunningly effective deployment of sound to convey emotional truth.

The Geography of a Hangover

The lyrical journey itself is cinematic and narrative-driven. The story begins indoors, with the physical pain of the hangover: “no way to hold my head that didn’t hurt.” The famous image of the “cleanest dirty shirt” is a perfect encapsulation of a man whose priorities have collapsed. This small detail tells us everything about his circumstances—the laundry pile, the recent desperation, the shallow attempt at recovery. It’s not just a song about a physical state; it’s a portrait of moral and emotional depletion.

When the narrator stumbles out into the “sleepin’ city sidewalk,” the song opens up to a world he is excluded from. The smell of “someone fryin’ chicken” and the sight of a father and a laughing little girl are not moments of comfort; they are cruel reminders of connection, stability, and normalcy that he has lost.

“It took me back to something that I’d lost somehow, somewhere along the way.”

This single line is the core emotional anchor of the entire piece of music. It’s a moment of piercing clarity, a nostalgic pang so sharp it cuts through the chemical haze. The contrast between his internal world (despair, isolation) and the external world (joy, community, the ringing of a lonely church bell) is what gives the song its devastating power. For anyone who has ever faced a morning after with regret—whether from a true addiction or just poor choices—this song is a mirror held up to that specific, unforgiving light.

The power of the song lies in its refusal to look away. It’s a gut-wrenching admission of failure, delivered with the absolute integrity of a man who has seen the bottom and is not afraid to talk about the view. It stands as a monument to the honest songwriting Kristofferson mastered, and the absolute conviction Cash brought to everything he touched. It is a defining album track for Cash, a moment where his star power was bent not toward glamour, but toward profound, heartbreaking empathy. It’s the kind of song that makes you want to immediately look up guitar lessons—not to play flashily, but to learn how to communicate raw feeling with such economy.

Listening Recommendations

- Kris Kristofferson – “Help Me Make It Through the Night”: Shares the same era and composer, capturing a different but equally intimate moment of vulnerability.

- Merle Haggard – “Hungry Eyes”: A similar, documentary-style narrative detailing hard, lonely living with stark, empathetic detail.

- Willie Nelson – “Whiskey River”: Another outlaw-era anthem about self-medication and the brutal honesty of the morning after.

- Townes Van Zandt – “Tecumseh Valley”: A devastating folk narrative that uses simple language to paint a bleak, realistic portrait of a struggling life.

- Gillian Welch – “Revelator”: Modern folk that uses sparse instrumentation and rich, melancholic language to capture existential loneliness.

The true artistry of “Sunday Morning Coming Down” is that it doesn’t judge the man on the sidewalk. It simply observes his pain, offers a beer for breakfast, and walks with him through the long, quiet hours. It is an enduring testament to the grit and grace of a specific era of country music—one that dared to be both commercially successful and unflinchingly true. Listen again, and hear the silence of that city sidewalk. It’s still ringing.