The room is dark, save for the blue glow spilling from the home audio setup across the floor. You can hear it best when the traffic outside stills for a moment—a faint, archival hiss, the ghost of magnetic tape clinging to the master. Then the acoustic guitar comes in, a stark, decisive strum that cuts through the silence like an axe blade hitting frozen spruce. This is the sound of a story beginning, the kind that demands you lean in, even if that story is framed by a punchline colder than any joke.

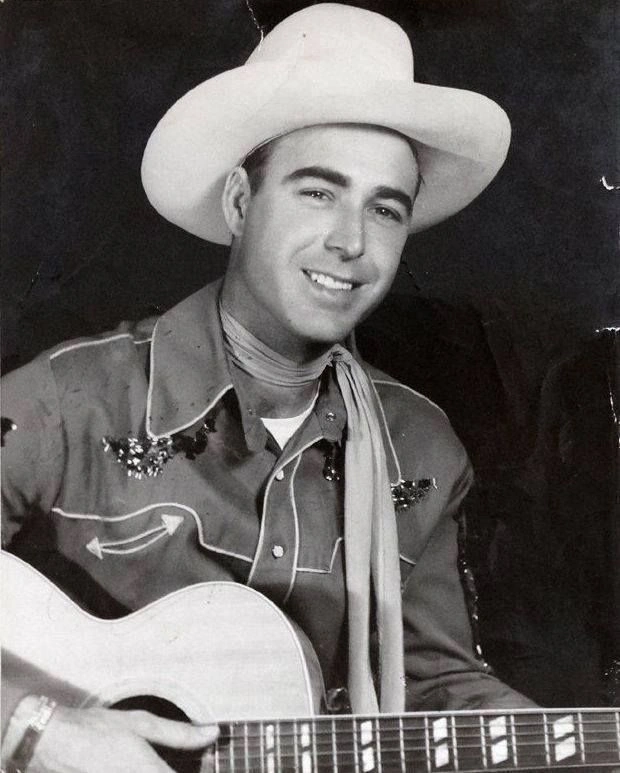

That introductory moment belongs to Johnny Horton’s “When It’s Springtime In Alaska (It’s Forty Below).” It is a piece of music that is both a rugged travelogue and a devastating, short-story tragedy, all condensed into two-and-a-half minutes of pure, late-1950s Columbia country. It was released in 1959 on the heels of a career shift that cemented Horton’s place in history, propelling him past his initial rockabilly and honky-tonk hits toward what became known as the ‘saga song.’

A Northern Light in the Career Arc

Horton, who was already a veteran of the Louisiana Hayride and had signed to Columbia Records in 1956, had found moderate success with the driving, hard-edged honky-tonk of “Honky Tonk Man.” But the material that truly defined his brief, brilliant late-career run—culminating in the worldwide smash “The Battle of New Orleans”—was this new strain of historical or geographical narrative. “When It’s Springtime In Alaska (It’s Forty Below)” was a crucial step in this direction, predating “Battle” and becoming Horton’s first number one hit on the country charts.

It was produced by Don Law, a legendary figure in Nashville who also worked with Lefty Frizzell and Ray Price, and who helped shape the sound of Columbia’s Nashville division during that fertile post-war era. Law’s production here, though straightforward, is masterful in its clarity and restraint. He allows the narrative and the vocal performance to sit squarely in the foreground, supported by an arrangement that is spare but emotionally potent.

“The true artistry of this recording lies in its ability to make the listener physically feel the biting wind and the cold dread of the Yukon saloon.”

The song itself was written by Tillman Franks, Horton’s manager and bass player, a man with a genius for packaging vivid, cinematic stories into singable country songs. It tells the grim, vivid tale of a prospector’s return to Fairbanks after two years ‘out prospectin’, and his fatal encounter with a saloon singer and her jealous man.

The Ice-Lined Sound: Instrumentation and Texture

The instrumentation is a lesson in how much can be achieved with relatively little. The rhythm section—bass and drums—is utilitarian, a steady, low-slung pulse that suggests a long, slow slog through heavy snow. It never rushes the narrative, instead creating a sense of inevitability. The true color comes from the string section—not a soaring, saccharine orchestral wash, but a controlled, almost mournful texture that sits just beneath Horton’s voice. These strings, likely arranged to evoke the vast, cold emptiness of the setting, swell at critical emotional points, providing an understated sense of high drama.

The electric guitar work is pure, unadorned Nashville Sound grit. There is a clean, slightly twangy tone, playing simple, effective fills that echo the verses. These are not showy rockabilly solos; they are narrative punctuation, often dropping into the mix with a quick, two-bar phrase that carries the weight of the lonely mile or the imminent threat of violence. Listen closely to how the reverb-drenched fills on the upper strings of the guitar seem to hang in the air, mimicking the steam from a man’s breath in frigid air.

In this classic arrangement, the piano is notably absent from the main instrumentation, yielding the harmonic space completely to the guitars and strings. This choice strips away any sense of honky-tonk frivolity, leaning instead on the more somber, folk-ballad aspect of the material. However, the melodic simplicity of the vocal line suggests this song would translate beautifully to a simple sheet music arrangement for voice and piano, relying on the singer’s theatrical delivery for impact.

A Master of Contrast and Delivery

Horton’s vocal delivery is the heart of the matter. He sings with the confidence of a man who has lived the story, a voice equally capable of projecting the friendly, slightly naive excitement of the prospector and the sudden, gut-wrenching realization of his fate. The contrast is devastating. The opening verse is jaunty and full of optimism, a man returning to civilization. The final stanza, however, shifts completely.

The infamous punchline, “When it’s springtime in Alaska, it’s forty below,” is one of the most brilliant double-entendres in country music. In the first half of the song, it’s a geographical joke, a wry comment on a brutal climate. By the end, after Big Ed’s knife has been thrown, the line becomes a marker of death, an epitaph. The shift in tone—from travelogue to tombstone—is where the song earns its reputation. This masterful handling of contrast turns a simple country single into a profound statement on fate and isolation.

For those engaging with this kind of archival sound, a note on playback: finding a clean, dynamic transfer is crucial. Investing in premium audio equipment can really unlock the subtleties of Don Law’s production, allowing the subtle string textures and the controlled attack of the rhythm section to emerge from the analog warmth.

This 1959 single was not part of a pre-planned studio album of new material, but was later collected on various releases, including The Spectacular Johnny Horton. Its success signaled the true beginning of his short-lived yet profoundly influential saga-song era. He tragically died the following year, but his small canon of narrative songs continues to be a touchstone for writers and performers looking to bring cinematic scope to country and folk music. It reminds us that sometimes the greatest tales are told in the starkest, coldest terms.

Suggested Listening Recommendations

- Tex Ritter – “High Noon (Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darlin’)”: For a similar marriage of narrative songwriting and cinematic, emotional weight from the same era.

- Marty Robbins – “El Paso”: Another sweeping, narrative-driven ballad from 1959, focusing on a man whose fate is sealed by a jealous love.

- The Louvin Brothers – “Knoxville Girl”: Offers the dark, traditional murder ballad core that underlies Horton’s song, stripped of the saga-era production.

- Johnny Cash – “The Ballad of Ira Hayes”: A later saga song, sharing the focus on a real-life, tragic American figure and a stoic delivery.

- Claude King – “Wolverton Mountain”: For another example of the early 60s trend toward regional, character-driven story songs with a clear moral or danger.