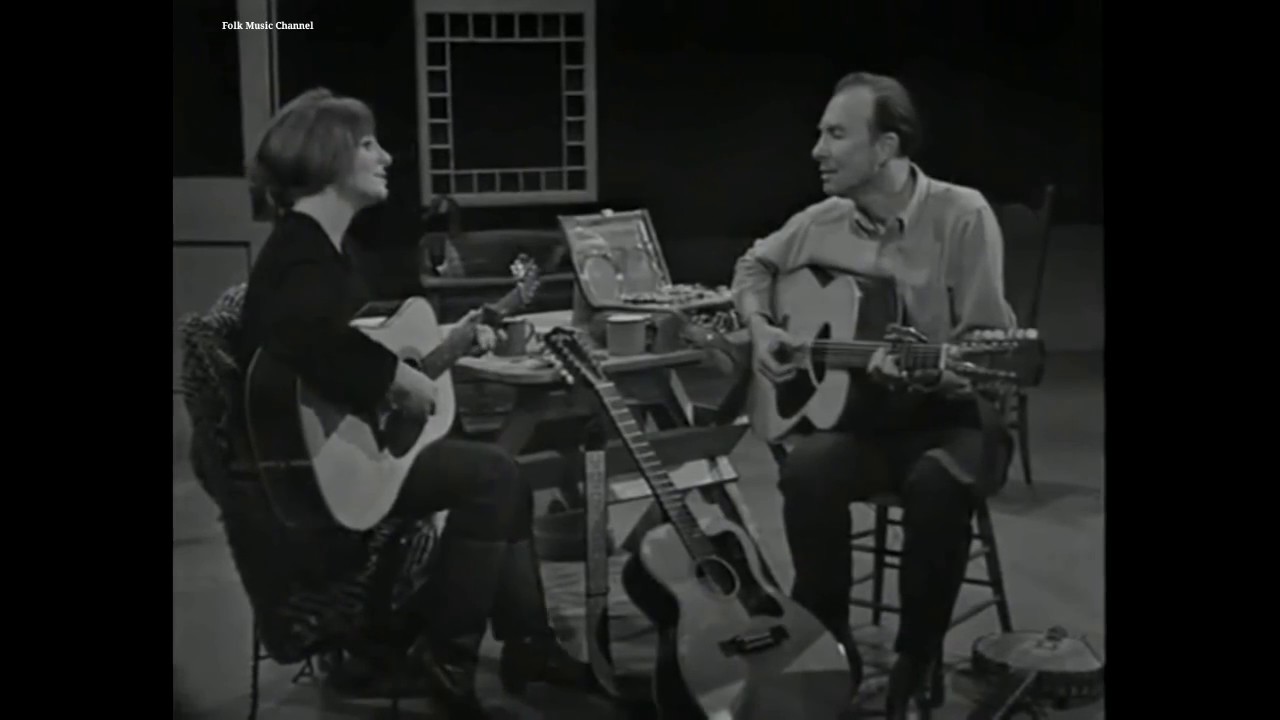

The air in the room is thin. You can almost feel the lack of a large audience, the absence of theatre. This is not the echo of Madison Square Garden; it’s a small, stark television studio in New Jersey, the kind of place where the technical constraints—the single mic, the cheap black and white camera—force the focus down to the absolute essence. It’s 1966, and the folk revival has already mutated, giving way to the electric shock of folk-rock. Yet, here, captured on Pete Seeger’s low-budget, deeply earnest public television show, Rainbow Quest, is a piece of music that defies the rush of the era: “Turn! Turn! Turn! (To Everything There Is a Season),” performed by its adapter, Pete Seeger, alongside Judy Collins.

This is not the jangling, pop-chart rocket that The Byrds had launched a year earlier. That version, an iconic moment of electric transformation, had taken the song to number one. This is the source code, the quiet gravity of the original folk intention.

Collins had already recorded a chamber-folk arrangement of the song, arranged by Jim McGuinn (later Roger McGuinn of The Byrds), for her essential 1963 album, Judy Collins 3, on Elektra Records, well before its electric destiny was revealed. McGuinn’s initial arrangement was delicate, prefiguring the soaring melodies he would adapt for the rock arena. But this 1966 rendition, shared between the songwriter and the genre’s purest voice, stands apart as a moment of profound, unadulterated transfer of wisdom. It’s an artifact for anyone seeking premium audio clarity in musical intent, stripped bare of commercial polish.

The Sound of Dialogue: A Study in Restraint

The arrangement for this track is a masterclass in minimalism. There is no rhythm section, no soaring orchestral swell, just two voices and two simple instruments. Seeger’s guitar provides a bedrock, his playing functional and rhythmic, a steady pulse of open chords that frame the timeless lyric adapted from the Book of Ecclesiastes. His guitar is a well-worn companion, its timbre warm and woody, lacking the bright, almost metallic attack of a freshly strung studio instrument.

Collins takes the lead vocal. Her voice, already a thing of crystalline beauty, is miked close, almost intimately. She eschews the wide, operatic vibrato of her later work, favoring a controlled, almost whispered delivery. The dynamic range is remarkably restrained, lending a sense of hushed reverence. When she sings, “A time to be born, a time to die,” the gravity of the words settles without being forced.

Seeger joins her for the harmony, his voice a rugged, slightly lower counterpoint that locks in with a familial resonance. It’s the sound of two people on a porch, contemplating the vast cycle of history. There’s no grandstanding; the focus is entirely on the words. In a moment of stark contrast to the baroque arrangements that would soon dominate pop, the track showcases the incredible power held in acoustic simplicity.

The Career Arc: Passing the Torch

The context of this performance is crucial to its meaning. Seeger, born 1919, was the elder statesman, the tireless crusader who had weathered blacklisting and commercial indifference, always tethered to the communal heart of folk music. This song, which he adapted in 1959, had been his gentle, yet firm, message of peace and resilience in the face of Cold War anxieties.

Collins, a generation younger, was the new face of the folk movement—a classical piano prodigy who chose the guitar and the troubadour’s path. By 1966, she was on the cusp of an incredible breakthrough. She was the essential interpreter, bringing the material of Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, and Joni Mitchell to the masses. She was translating the raw, political power of the old guard into a delicate, sophisticated language for the new, educated, questioning youth.

Watching them interact, even in this small frame, you see the changing of the guard, but without rivalry, only respect. Seeger is the humble anchor, strumming the original notes. Collins is the soaring interpretation, carrying the melody like a sacred flame. This track isn’t a studio single; it is a collaborative sermon, a vital historical document proving the inherent flexibility and power of the folk tradition.

“It is a sound defined less by its polish and more by the quiet certainty of shared belief.”

The 1960s were characterized by explosive change, a dizzying acceleration of culture and conflict. The original text from Ecclesiastes, with its cyclical declaration—a time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing; a time to gain, and a time to lose—provided a philosophical anchor for a generation grappling with Vietnam, Civil Rights, and radical societal shifts. This version, with its unhurried tempo, is a meditative pause in the storm. It’s an antidote to urgency, a deep breath when the world demanded gasps.

It has always been a marvel of songwriting that such ancient text could feel so utterly contemporary, a testament to Seeger’s sensitive editing and melody construction. The concluding line, Seeger’s own contribution—”A time for peace, I swear it’s not too late”—transforms the historical observation into a fervent, forward-looking prayer. Collins delivers this final plea with a measured intensity, the quiet hope in her voice more convincing than any shouted protest. This performance serves as a powerful reminder that sometimes the most monumental shifts in understanding begin not with a roar, but with a whisper, passed between two people in a small, quiet room.

Micro-Stories: The Enduring Echo

I often recommend this version to people who have only ever heard The Byrds’ recording. It’s like discovering the blueprint of a majestic cathedral. One listener, I recall, mentioned using this recording during an all-night drive across the country, the repetitive, soothing cadence of the guitar and the voices providing a kind of ambient, non-denominational meditation. Another, a composer, used its structural simplicity as a teaching tool, illustrating how complex thematic material can be expressed with only two chords and a perfect melody. The enduring appeal lies in its utility; it’s not merely a song, but a framework for navigating uncertainty. This performance, rarely compiled and often overlooked, remains a vital, beating heart of the American folk canon.

The simplicity of the instrumentation and the straightforward lyrical delivery make this 1966 track an essential piece of music for any serious collector’s listening rotation. It distills the complex spiritual and political tapestry of the 1960s down to a single, clear, enduring statement. It is a gift passed down.

Listening Recommendations

- Pete Seeger – “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” (Adjacent Mood): A similarly poignant meditation on loss and cycles, built on simple acoustic foundations.

- Joan Baez – “Diamonds and Rust” (Adjacent Mood/Era): Showcase of a pristine soprano voice articulating deep, personal wisdom over sophisticated acoustic backing.

- The Byrds – “Mr. Tambourine Man” (Era/Arrangement Contrast): The seminal folk-rock hit, illustrating the exact moment the folk movement went electric and gained a pop beat.

- Judy Collins – “Since You Asked” (Artist Career Arc): Later, self-penned work demonstrating her continued focus on intense emotional and lyrical clarity.

- The Kingston Trio – “Tom Dooley” (Era/Acoustic Simplicity): Early folk revival track demonstrating the power of close harmony and straightforward acoustic guitar arrangement.

- Simon & Garfunkel – “The Sound of Silence” (Acoustic Version) (Adjacent Mood): Captures the same sense of quiet, intimate communication and lyrical weight as the Collins/Seeger duet.