A call-and-response of faith and memory — where generations are summoned through song, and belief becomes a living tradition.

When Kenny Rogers recorded “Children, Go Where I Send Thee,” he stepped into one of the oldest currents of American sacred music and reshaped it with quiet authority. The song itself is a traditional African American spiritual, with roots reaching back to the 19th century, long before charts, studios, or commercial recordings existed. As such, it never had an original “debut position” in the conventional sense. Yet Kenny Rogers’ recorded version, released on his 1981 holiday album Christmas, found a strong presence on adult contemporary and seasonal radio playlists, and the album itself reached No. 1 on the Billboard Top Country Albums chart and No. 6 on the Billboard 200. In that context, the song gained a renewed life for a wide, attentive audience.

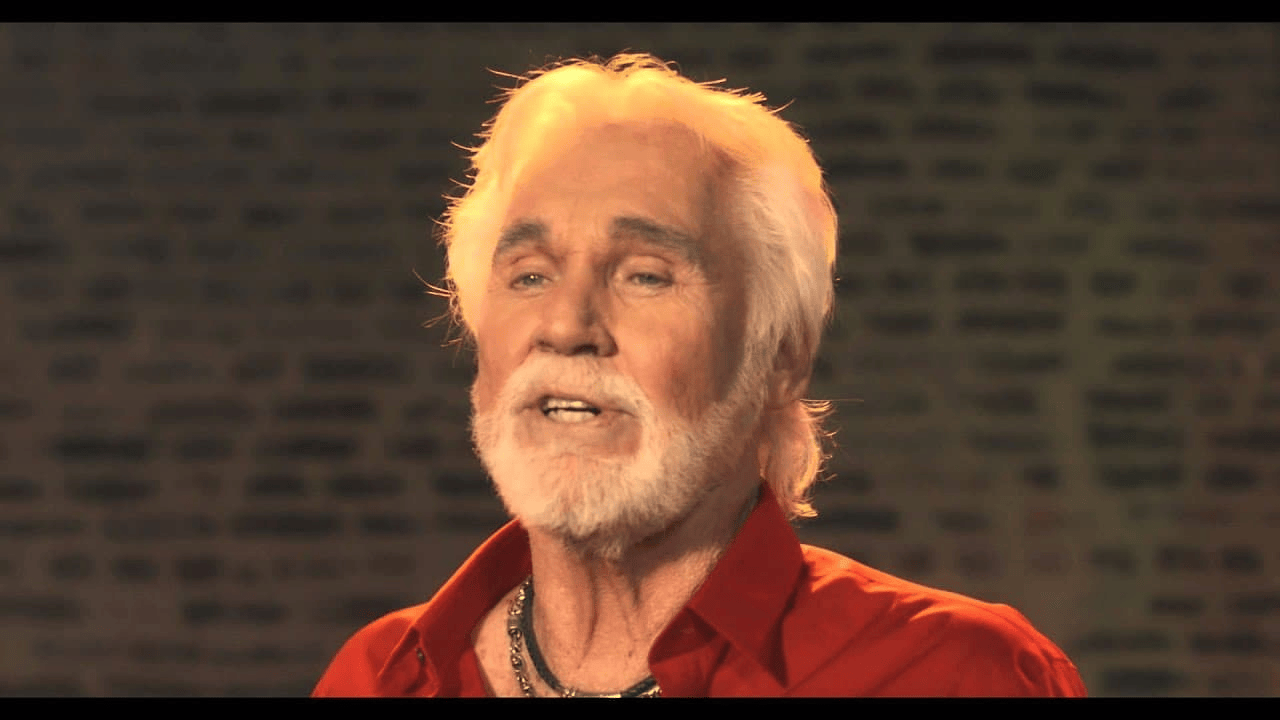

By the early 1980s, Kenny Rogers was already one of the most recognizable and trusted voices in American music. His strength lay not in vocal acrobatics, but in clarity, warmth, and narrative conviction. Those qualities made him particularly suited to “Children, Go Where I Send Thee,” a song built not on melody alone, but on accumulation, repetition, and shared memory. This is music designed to be passed down, not merely performed.

The structure of the song is deceptively simple. Each verse builds upon the last, counting upward and assigning symbolic meaning to each number — biblical references layered one upon another. One for the little bitty baby, two for Paul and Silas, three for the Hebrew children, all the way through twelve for the twelve disciples. The power of the song lies not in surprise, but in recognition. Each repetition reinforces belonging, continuity, and faith as something learned by listening and remembering.

In Kenny Rogers’ interpretation, the song becomes less about instruction and more about invitation. His delivery is steady and grounded, never hurried. He allows the call-and-response format to breathe, echoing the way such songs would have lived in churches and homes long before microphones existed. The arrangement supports this approach — modest, rhythmic, and communal rather than ornate. The emphasis remains on the message, not the performer.

Historically, “Children, Go Where I Send Thee” has occupied a unique place in American music. It is both a Christmas song and something older, deeper — a spiritual that predates seasonal categorization. It has been recorded by artists as varied as The Golden Gate Quartet, Johnny Cash, and Odetta, each bringing a different emphasis. Where Cash’s version leans toward stark proclamation, Kenny Rogers offers reassurance. His voice suggests continuity rather than command, guidance rather than decree.

The meaning of the song unfolds gradually. On the surface, it is a counting song, almost childlike in structure. Beneath that simplicity lies a profound idea: faith as something cumulative, built layer by layer across time. Each number depends on the ones before it, just as belief, tradition, and identity are shaped through repetition and shared experience. The song does not argue or persuade. It assumes that memory itself carries authority.

What makes Kenny Rogers’ version especially effective is his respect for restraint. He does not modernize the song unnecessarily, nor does he embellish it with excessive sentiment. Instead, he stands back and lets the song’s ancient architecture hold. This approach aligns with much of his finest work — the belief that the most powerful stories do not need to be pushed.

Although “Children, Go Where I Send Thee” was not released as a charting single, its presence on a best-selling album ensured its reach. More importantly, it secured a place in private listening rituals, especially during reflective seasons. The song’s repetitive structure lends itself to quiet contemplation, its message unfolding differently with each hearing.

In the broader scope of Kenny Rogers’ career, this recording reveals another dimension of his artistry. Known widely for narrative country songs and crossover hits, he also understood the importance of roots — of music that exists beyond individual authorship. By recording a traditional spiritual, he placed himself within a lineage rather than above it.

Ultimately, “Children, Go Where I Send Thee” as sung by Kenny Rogers is not about spectacle or performance. It is about continuity. About voices calling out across time, and others answering back. It reminds us that some songs are not meant to belong to one era or one artist. They are meant to travel — carried forward by those willing to listen, remember, and respond.

Long after trends fade and charts change, this song endures in a quieter way. Not as a hit to be counted, but as a calling — steady, insistent, and timeless — asking each generation to recognize where it comes from, and to carry that knowledge forward, one verse at a time.